Choice in name only? Plenty of rules keep students from participating in Wisconsin’s choice programs

May 2, 2017

By Ola Lisowski

MacIver Institute Research Associate

When the state legislature created Wisconsin’s Special Needs Scholarship Program (SNSP) in 2016, Milwaukee educator William Koehn knew his school had to participate.

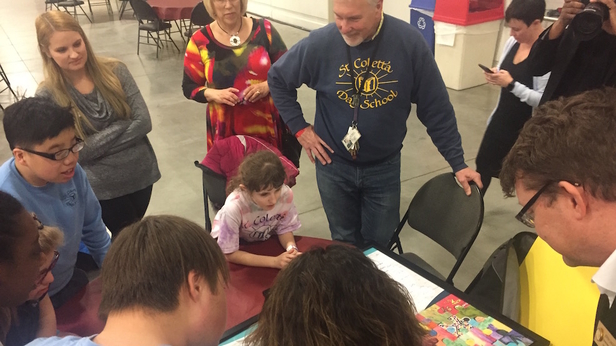

“Because we serve students who are all somewhere on the special needs spectrum, it was extremely important for us to be able to take advantage of the special needs scholarship program, and we did just that,” said Koehn, administrator and lead teacher at St. Coletta Day School of Milwaukee.

St. Coletta, which serves 24 students with special needs, recently celebrated its 60th year. It was initially established by a group of parents dissatisfied with schooling options in local public or private schools. The school has participated in the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program for six years, which Koehn says has drastically changed the kinds of services he is able to provide his students.

“A year ago, the special needs voucher came into view, and we looked at that program and said, ‘Oh my gosh, this is really going to be a game changer for our school. At the time we had 24 students, and 22 qualified for the special needs voucher,” Koehn said. “It really did allow us to dream a bit.”

Barriers to Choice

In order to participate in the SNSP, students must have been denied admission in the state’s open enrollment program. That program, which has existed since the 1998-99 school year, allows students to transfer from a “home” public school district into another public school district where they do not reside. With more than 50,000 students participating every year, open enrollment is often called the state’s largest school choice program.

State law describes in detail why a student may be denied open enrollment, and districts are bound by statutory restrictions. For one, space must be available in the applicant’s grade. If a student has an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and the district they’re applying to doesn’t offer such services, the student may be denied. Behavioral issues and truancy may also come into play. If there are more applicants than spots available, districts must select students by a blind lottery.

If a student has an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and the district they’re applying to doesn’t offer such services, the student may be denied. Behavioral issues and truancy may also come into play. If there are more applicants than spots available, districts must select students by a blind lottery.

Districts can’t refuse a student applying for open enrollment for reasons such as academic performance. For many students and their families, it’s simply the luck of the draw.

On top of the open enrollment denial requirement, students must have attended a public school for the entire previous school year before they’re eligible for the scholarship program.

Koehn and his staff have worked diligently to help families deal with the program’s barriers to entry. He says that many families struggle with the barriers. It was particularly difficult for students who were already part of the school, because going forward, none would meet the requirement of having attended a public school in the prior year. Koehn described them as having “one shot at this.”

“If the purpose of the choice programs and scholarship program is to benefit the individual, the student, and at the same time to help the family, it just seems like this is an unnecessary additional burden that the families have to deal with,” Koehn said.

“It’s a bit discouraging for me to talk to potentially new students coming into our school to say ‘Well, this is a great program, is your child currently in a public school and have they been there for the entire school year?’ It seems to be a barrier, a deterrent, which translates into discouragement for the parent and ultimately for the student.”

Unlike the statewide, Milwaukee, or Racine school choice programs, the SNSP does not include any income limits on participation. Participation in the Milwaukee and Racine programs is capped at 300 percent of the Federal Poverty Level, or nearly $73,000 annually for a family of four. The statewide program cap is set lower, at 185 percent, or less than $45,000 annually for a family of four.

Families found the lack of income cap particularly exciting, Koehn said, because regardless of income level, students with special needs require extensive services. Koehn said his school worked hard to keep tuition at modest levels, but between other medical issues and expenses that families are dealing with, many parents – especially those just over the 185 percent federal poverty level – still struggled with the cost.

“When those particular families realized what the special needs scholarship program was all about, and I explained to them that yes, they would qualify, they were ecstatic,” Koehn described. “That took that whole burden, that whole stress factor, to a whole new lower level, and they could focus on being the parents that they needed to be, knowing that their child could stay in a school where they are meeting success, and where it could be less of a financial burden on them.”

Congrats to @LeahVukmir, @JohnJagler who received awards made by the 1st class of students who received Special Needs Scholarships #wiright pic.twitter.com/ybzIAns0Vp

— MacIver News Service (@NewsMacIver) April 5, 2017

Pictured: William Koehn (left), speaking with Rep. John Jagler and Sen. Leah Vukmir after presenting them with an award made by his students.

In describing the future of Wisconsin’s school choice movement, Koehn said he hopes barriers such as denial in open enrollment participation could be eliminated. He lamented the misinformation surrounding school choice programs, and expressed a solidarity with public schools.

“I am a big proponent of public school education, just as I am a proponent of private school education. It takes all of those,” Koehn said. “To use that worn out phrase, ‘it takes a village.’ It really does. Whatever’s going to work for that individual student is what we need to support… I really do think that if nothing else, if we can help continue to get the word out there that it takes all kinds of choices for the students and to find the best fit for that individual, and if that happens to be a private school like St. Coletta Day School where we specialize in kids with specific learning styles and challenges, then that’s the place for them.”

Opportunity Capped

An hour north of St. Coletta Day School stands Sheboygan Lutheran High School, with an enrollment of 177 students. The high school has participated in the statewide choice program since its inception, and 25 students currently attend thanks to vouchers. While a handful of new voucher students are able to attend the school every year as a result of graduations, the pupil participation cap has stalled growth in the program.

In the current school year, only 2 percent of a public school district’s student population can participate in the statewide choice program (Wisconsin Parental Choice Program, or WPCP). That cap will increase by 1 percent every school year until it hits 10 percent in 2025-26, after which it will be eliminated. The district enrollment limits  were established in the 2015-17 state budget. For districts like Sheboygan, where several schools participate in the choice program, the limited number of seats are divided up equally by school.

were established in the 2015-17 state budget. For districts like Sheboygan, where several schools participate in the choice program, the limited number of seats are divided up equally by school.

Students who are not already in public school are only eligible for entry into the choice program during grades K-4, K-5, 1st, and 9th. That makes the district enrollment caps all the more important.

“When they froze it at 1 percent, we weren’t able to grow, and then they put on those entry points as well,” explained Paul Gnan, executive director at Sheboygan Lutheran High School. “Families that missed it by one year because they were put on the waiting list no longer have a shot in the lifetime of their student to get into the program.”

Gnan, who has worked at the school for three years, said Sheboygan Lutheran is “blessed” with good support and financial aid endowments. About half of the families who don’t get a voucher still come to the school under a financial aid package. Still, just about half of the families on the waiting list can’t afford the private school tuition, and must find another option.

“The outstate people are getting, in my estimation, unfairly treated,” Gnan said, referring to the 185 percent FPL income limit for the statewide program, compared to 300 percent for Racine and Milwaukee. “I’d like to see the income level raised from 185 to 220 at the minimum, I don’t know if we can make it all the way to 300, but something along those lines.”

Ultimately, Gnan said, no one in the state can actually explain the state’s school funding formula, which he says is different in each community. He’s concerned about the lack of options for outstate families, especially those just above the 185 percent Federal Poverty Level.

“The state has to set aside money regardless of where you go to school for those entry levels,” Gnan said. “There’s a misunderstanding that we’re taking money away from the public schools, but they weren’t getting that money anyway, necessarily.”

Foreclosing College Opportunity

While all Wisconsin taxpayers see their dollars sent to K-12 schools, not everyone gets to see those dollars in action. Students at Shoreland Lutheran aren’t allowed to participate in publicly-funded programs such as Youth and Course Options, which let students take courses at local colleges. About one-third of the students at Shoreland Lutheran are attending with a voucher through the Racine Parental Choice  Program.

Program.

Paul Scriver has been principal at Shoreland Lutheran for eight years. He believes that students whose families pay taxes to fund the district should be able to participate in the same programs.

“We have UW-Parkside just three miles down the road from us, and Gateway [Technical College] too, so it would be very convenient for our kids to take college classes at one of those two schools while still attending high school,” Scriver said. “Students with motivation and the gifts to do that could not only enhance their educational experience during their high school years but also really increase their opportunities then in college, as they could eliminate certain general ed courses. That might allow them to pursue other courses, free up their schedules, maybe graduate early from college, too.”

Shoreland Lutheran was part of a group of several schools that asked the state to consider letting private school students participate in the Youth Options program before the choice program came into play.

While it’s not an issue his school hears about every day, Scriver said that it has, at times, played into why parents choose not to send their children to Shoreland Lutheran.

“Parents will say, our child has more options if they attend such-and-such a school, and then they have an opportunity to not only graduate early but to take care of a year of college before they get there,” Scriver said. “There are some huge advantages that parents are missing out on.”

Students new to Wisconsin are also missing out on educational opportunities. Currently, students have to have attended a public school in the state for the entire previous school year to participate in choice. Even students who would otherwise qualify under income and residency requirements are locked out.

Scriver agreed with Gnan that the income limit for the statewide program poses a significant barrier for students seeking access to the choice system. “It’s not about poverty, but it’s about really being able to afford private education. Even if you make a little more money, that’s not always still possible.”

Gov. Scott Walker’s 2017-19 budget doesn’t include a significant expansion of the state’s choice programs, unlike the last few budgets. One provision, however, would allow students who are new to the state to participate.

As the MacIver Institute has previously reported, parental choice supporters are still hoping for more opportunities. They may find it in the Legislature, where lawmakers have expressed interest in continuing to expand the programs.

Choice educators assert that education must ultimately about the students.

“All these programs are designed to help kids,” Scriver said. “If we can all just stay focused on that, that would be good.”

Follow the MacIver Institute for continued coverage as the Joint Finance Committee begins voting in May.