A simple, cost-effective way to ease the shortage of dental care in Wisconsin

By Chris Rochester

Director of Communications

The John K. MacIver Institute For Public Policy

and

Jennifer Minjarez

Policy Analyst with the Center for Health Care Policy

Texas Public Policy Foundation

Download a PDF of this report here.

Introduction

Strict licensure requirements, a general shortage of dental providers, and geographic constraints are limiting access to critical dental care in Wisconsin. In fact, 65 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties have at least one area that qualifies as experiencing a shortage of dental providers. The problem is particularly acute in areas with higher populations of low-income and minority individuals. Our research shows that easing regulations and allowing more dental professionals to conduct routine dental work, under the supervision of a licensed dentist, is a pragmatic and sensible solution to Wisconsin’s dental shortage.

If Wisconsin allowed the practice of dental therapy, there would be more access to important dental care. Dental therapists are mid-level dental practitioners, similar to nurse practitioners or physician assistants in medicine. Under general supervision of a dentist, dental therapists can perform a wider range of routine procedures than a dental hygienist, including drilling, filling cavities, and performing nonsurgical extractions.

The shortage of adequate dental providers means many people in Wisconsin are not getting the dental care they need.

The problem is particularly concerning where it involves children’s access to dental care. In 2016, more than 550,000 children (ages 1-18) had dental benefits through Medicaid in Wisconsin.

However, even though these children had dental coverage, the vast majority of them, 67 percent, received no dental care—the worst rate in the country.

Clearly, improving access to dental care is critical to making progress on health care issues in Wisconsin.

Oral Health In Wisconsin

Oral health plays a significant role in a person’s physical and mental wellbeing. In 2000, the Surgeon General released a report on oral health that featured evidence of association between oral infections and diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and adverse pregnancy outcomes (HHS, 109). Dental disease causes children to miss over 51 million hours of school each year, and adults lose over 164 million hours of work (2-3). Furthermore, oral conditions can negatively affect self-esteem. Twelve percent of Wisconsin adults report that the appearance of their teeth affects their ability to interview for a job (ADA).

Dental care is a lifelong necessity. Routine preventive care and healthy oral habits early on can prevent painful and costly dental disorders in the future.

The rate of dental disease and dental utilization among Wisconsinites gives us a better picture of oral health needs across the state.

In 2014, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS) published a survey of oral health among Wisconsin Head Start children, age three to five. It found that 41 percent of Head Start children had experienced tooth decay, 23 percent had untreated tooth decay, and 20 percent had early childhood tooth decay (DHS, 8).

The Head Start survey also showed that 69 percent of Asian children had experienced tooth decay, compared to 39 percent of Hispanic children, 38 percent of African-American children, and 36 percent of white children (11). African-American children had the highest rates of untreated tooth decay (28 percent), compared to 20 percent among white children.

More than 550,000 Wisconsin children were eligible for Medicaid for 90 continuous days in 2016, about 43 percent of all Wisconsin children (FY 2016 CMS-416). However, only 42 percent of these Medicaid children received any dental or oral health services during the year. Thirty-one percent received dental services from a dentist or practitioner under the supervision of a dentist, while 14 percent received oral health services from a non-dentist practitioner, such as a primary care provider.

The dental care picture for adults in Wisconsin is not much better. A DHS survey found that 15 percent of Wisconsin adults had untreated tooth decay, 17 percent had gum disease, and 16 percent needed treatment for oral decay, abscesses, or lesions (DHS, 10-14).

Oral health among adults varies widely across income groups, racial/ethnic groups, and groups with different levels of education. Twenty-nine percent of low-income adults, those earning less than $25,000 per year, had untreated decay, compared to 16 percent of adults in the next highest income group, earning $25,000 to $49,999 per year (12). Thirty-two percent of low-income adults needed dental care for decay, abscesses, or lesions, compared to 18 percent of adults in the next highest income group.

Among low-income adults who had not visited a dentist in the past 12 months (2015), 50 percent cited cost as a reason, 42 percent cited trouble finding a dentist as a reason, and 42 percent cited inconvenient time or location as a reason (ADA).

The DHS survey also found that “[African-Americans] were significantly twice as likely to have untreated decay and a need for dental care as whites…while racial/ethnic groups were also significantly more likely to report having oral health problems and difficulty gaining access to dental services” (4). Sixty percent of African-American adults reported having poor oral conditions, compared to 39 percent of Hispanic adults, and 23 percent of white adults (15).

Education was also associated with oral health. Thirty-nine percent of adults with less than a high school education had untreated tooth decay, and 42 percent needed treatment for decay, abscesses, or lesions. Only 20 percent of adults with a high school degree or equivalent had untreated decay, and 21 percent needed treatment (12).

According to the Wisconsin Oral Health Coalition (WOHC), “there are many special populations in the state with an increased disease burden that needs to be addressed, including: people with disabilities, long-term care residents, individuals with HIV/AIDS and those in the corrections system” (WOHC, 11). These populations tend to be more susceptible to dental disease and may have difficulty maintaining healthy oral habits at home.

For example, adults with disabilities had higher rates of untreated tooth decay and were more likely to report poor oral conditions than adults without disabilities (4). Forty-two percent of adults living in nursing homes had untreated tooth decay and only 52 percent reported visiting a dentist in the past year.

Wisconsinites are not receiving dental care early or regularly enough. Furthermore, the prevalence of socioeconomic disparities across all age groups suggests that the burden of oral disease is linked to access to care challenges. While certain populations have greater oral health needs than others, all Wisconsinites can benefit from better oral health strategies and plenty of dental care options.

Access To Dental Care In Wisconsin

One in five Wisconsin adults reported having a need for dental care and not getting it in 2015 (DHS, 14). A survey of those with unmet needs found the top three reasons for not receiving care were unaffordable costs (68 percent), inadequate insurance coverage (26 percent), and a lack of convenience getting care (23 percent). If policymakers want to increase access to dental care, they should consider market-based, supply-side reforms that address Wisconsinites’ top three barriers to getting care.

Costs

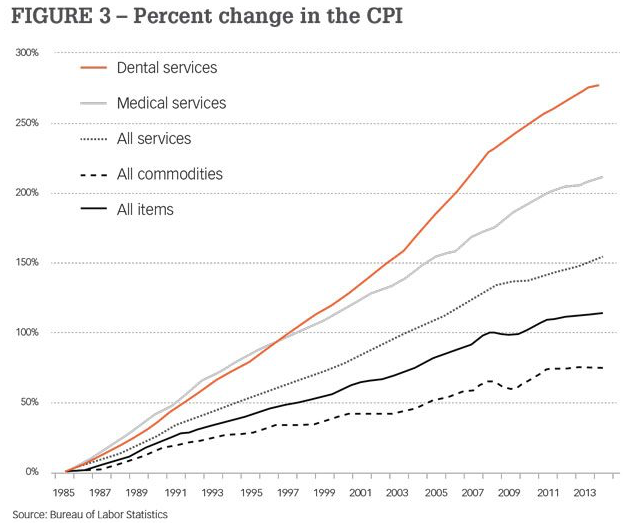

According to Dental Economics, “Since 1985, there has been a 279% increase in the cost of dental services,” far outpacing the growing cost of medical services and overall inflation.

Some of the most common dental procedures are fillings, root canals, extractions, and sealants. According to the American Dental Association’s (ADA) Survey of Dental Fees, an amalgam (metal) filling costs $130.16 on average in the East North Central Division, including Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio (ADA 2016, 34-45). Tooth-colored resin fillings costs $168.16, surgical extractions cost $264.04, and sealants cost $51.46 per tooth. These charges are expensive for Wisconsin families, and they add up fast for those who need multiple procedures at a time.

The cost of dental care is rapidly increasing from year to year. For example, the cost of molar root canals rose from $945.51 in 2013 to $995.92 in 2016, a $50 increase in only three years (ADA 2013, 34-45).

In a free market, service prices are determined by supply and demand, and competition puts constant downward pressure on costs. That is not always the case in dentistry. Wisconsin’s supply of dental care is constrained by the state dental practice act (Wisconsin Statutes Chapter 447) and licensure regulations (Wisconsin Administration Code Chapter DE). Under current law, dentists have a monopoly on performing the most needed dental procedures, such as fillings and extractions. Without competing delivery systems, there is no pressure on dentists to innovate or lower their charges. Dental care will continue to become less and less affordable until Wisconsin rolls back its licensure regulations, generates competition among providers, and allows them to adapt to Wisconsinites’ diverse needs.

Inadequate Insurance

Like the cost of dental services, the cost of dental insurance continues to rise. Private dental plan charges increased 10 percent for children and 7.7 percent for adults between 2003 and 2013—one of the highest overall increases in the country (ADA, 163). Dental coverage does not always translate into dental care. In 2013, 67 percent of children and 63 percent of adults with private dental plans visited a dentist. While these utilization rates were slightly higher than the national averages, they exhibited a decline in dental visits in Wisconsin since 2005.

Wisconsinites enrolled in public health insurance programs have even more difficulty accessing dental care. In addition to having limited coverage, they have narrow dental provider networks. Only 32 percent of Wisconsin dentists accept Medicaid or CHIP patients, compared to a national average of 38 percent (ADA). A DHS report on Wisconsin’s fee-for-service (FFS) Medicaid program shows that dentists’ participation rates are lower than other Medicaid provider types (DHS, 24).

Low participation rates among dentists likely contribute to low utilization rates among Medicaid enrollees. In 2016, more than 550,000 children received dental benefits through Medicaid, yet 67 percent received no dental care—the worst rate in the country (CMS).

Trouble Getting Care

Costs and inadequate insurance are not the only barriers to care. People who have coverage and can pay for dental services may have difficulty finding a provider, making a timely appointment, getting to the dental office, and maintaining regular visits. The shortage of dental care in Wisconsin stems from an inadequate network of providers and an over-regulated delivery system.

There are approximately 3,233 dentists in Wisconsin, or 56 dentists per 100,000 people (ADA). By the numbers, this seems like enough dentists to treat most Wisconsinites. In fact, a 2010 report commissioned by the Wisconsin Dental Association (WDA) asserts, “Wisconsin appears to have an adequate dental workforce to meet the current and future demand for dental services by the population that has high enough incomes and/or private dental insurance to purchase care in the private sector” (Beazoglou et al., 8). However, oral health outcomes and dental utilization rates indicate that millions of Wisconsinites in the private sector are not getting care. The reason for this is that care shortages are not simply driven by the number of providers relative to the state population. The type of providers available and how they are distributed across the state play a large role in determining when and where dental care is delivered.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), there are 138 dental health professional shortage areas (HPSA) in the state of Wisconsin (HRSA). Dental HPSAs are geographic areas, populations, or facilities that are experiencing a shortage of dental practitioners. To qualify as a dental HPSA, a geographic area must comprise 5,000 or more people per single dental provider, a population must comprise 4,000 or more people per provider, and a facility must comprise 1,500 or more people per provider. While dental HPSAs paint an incomplete picture of the state’s dental care shortage, again because it is purely quantitative, it is a useful measure of provider distribution. Sixty-five of Wisconsin’s 72 counties have at least one area that qualifies as a dental shortage.

Supply is only half the story. For example, Wisconsin has a large rural population that can benefit from alternative dental provider options. One in four Wisconsinites live in rural areas, about 1.5 million people (RHIH). While the 2010 WDA report identified a quantitative surplus of dentists in rural areas, it also found that rural residents “are in poor oral health relative to people in the larger counties” (Beazoglou et al., 6). In other words, supply is not the only factor driving the provision of dental care. Rural areas tend to have lower income and higher percentages of people enrolled in public health insurance programs than urban areas (6). They could benefit from a provider model that brings care closer to them, instead of requiring them to visit a dental office, and that utilizes mid-level dental practitioners who have lower labor costs than dentists, creating the potential for lower-cost services.

By expanding access to basic dental care, dental therapy could also help reduce emergency room visits. In 2015, there were 41,387 emergency department visits in Wisconsin for which a preventable dental condition was the primary or secondary diagnosis (WHA, 5). In 33,113 of those visits, preventable dental conditions were the primary diagnosis. At an average cost of $749 per emergency visit, that amounts to $25 million in preventable hospital costs (ADA 2015, 1). Fifty-six percent of dental-related ER visits were paid for by Medicaid. Further, since ERs are not equipped to provide comprehensive dental care, patients leave with the same underlying problems they come in with.

Increasing access to dental care with dental therapists can also help reduce opioid prescriptions. From 2007-2010, 1.7 percent of all ER visits were for non-traumatic dental conditions (NTDCs), and 50.3 percent of NTDC visits resulted in an opioid prescription, compared to 14.8 percent of non-NTDC visits (Okunseri et. al, 2). Furthermore, the prescription of opioids was highest among patients aged 19-33 years. This is a problem the Wisconsin legislature has sought to address—2015 Wisconsin Act 269 asked the Dentistry Examining Board to issue guidelines regarding best practices in the prescription of controlled substances (DEB). Expanding access to basic dental care and preventing tooth decay could stave off the need for opioid pain medications.

What Are Dental Therapists?

Dental therapists are mid-level practitioners in the dental profession, much like a physician assistant or nurse practitioner in medicine. These professionals would be trained in much the same way as other similar professions. They would be trained according to national standards developed by the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA), the sole agency recognized by the U.S. Department of Education to accredit dental education programs. CODA accreditation indicates a program has achieved a nationally accepted level of safety and quality.

Dental therapy is relatively new to the United States, but has been practiced abroad since the 1920s (WKKF, 2). Six states have made room for the profession, and it is flourishing in rural and underserved areas of Minnesota, one of just three states that allow dental therapists to practice statewide.

Dental therapists operate under the general supervision of a licensed dentist, which means the dentist is not required to be on-site. This enables dental therapists to travel to satellite sites away from the dental practice to perform basic care. Satellite sites might include rural satellite clinics, nursing homes, schools, facilities for people with disabilities, and other places where people would benefit from dental care coming to them instead of them traveling for dental care. This would help to solve the problem of geographic disbursement of dental practices and licensed dentists in rural and underserved areas. Dental therapists could take advantage of telehealth technology to consult with their supervising dentist when needed, and dentists would be responsible for determining the scope of practice, within legal bounds, of the dental therapists under their supervision.

Many of the consequences of dental disease such as pain, missed school, and missed work are caused by untreated tooth decay. However, under state law only dentists are allowed to fill cavities. Creating a new level of dental provider with a wider scope of practice could increase the number of trained, licensed professionals able to fill cavities and perform many other routine procedures.

Authorizing the licensure of dental therapists would not involve the creation of new bureaucracy or significant expenses to taxpayers. The Dentistry Examining Board would simply be directed to grant dental therapist licenses to those who meet the criteria, which would include the successful completion of relevant educational programs and examinations.

Conclusion

As our research has shown, a variety of factors are causing a growing shortage of dental care in Wisconsin, and the impact is being felt by all. From the very young to our grandparents living in nursing homes, Wisconsinites need more and better access to quality dental care. If Wisconsin permitted dental therapists, it would help to alleviate this crisis.