[bctt tweet=”The mainstream media and the Dem Party have focused much of their fire on AG @BradSchimel and his DOJ for a long-standing backlog of untested rape kits. That’s a faulty narrative, according to people in the know. #wiright #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”Victims’ advocate Ian Henderson of @wcasa_org said the organizations and individuals involved in the initiative, including @BradSchimel and the DOJ, have made fixing the failures of the past a priority. #wiright #wipolitics” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”The mainstream media and the Dem Party have focused much of their fire on AG @BradSchimel and his DOJ for a long-standing backlog of untested rape kits. That’s a faulty narrative, according to people in the know. #wiright #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”Victims’ advocate Ian Henderson of @wcasa_org said the organizations and individuals involved in the initiative, including @BradSchimel and the DOJ, have made fixing the failures of the past a priority. #wiright #wipolitics” username=”MacIverWisc”]

MacIver News Service | Sept. 10, 2018

By M.D. Kittle

MADISON – There’s been a lot of finger-pointing in the story of Wisconsin’s long untested rape kits.

No doubt there have been failures in a system that for decades allowed thousands of rape kits to pile up in law enforcement evidence shelves and hospital storage rooms.

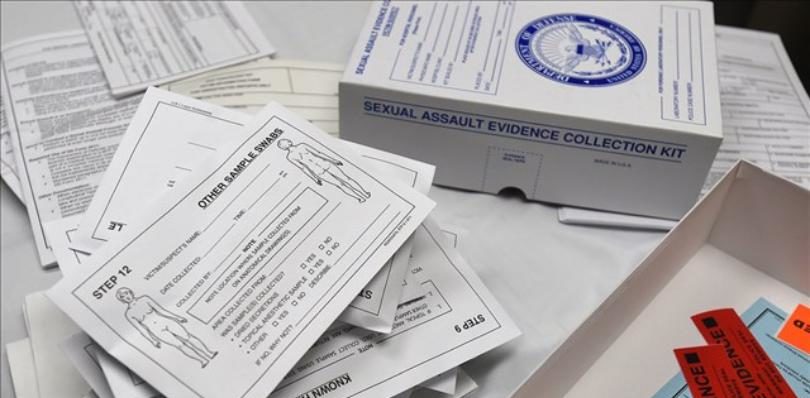

The thousands of backlogged rape kits – sexual assault forensic exams used to preserve DNA evidence that could lead to the arrest and conviction of an offender – extend as far back as the 1980s.

But in a fever-pitch election year the mainstream media and the Democratic Party political machine have focused much of their fire on Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel, a Republican, and his Department of Justice.

The press coverage and Dem press releases paint Schimel as a skinflint who put taxpayer savings ahead of swiftly clearing the backlog of some 4,100 untested sexual assault kits. He’s portrayed as an attorney general who sought out-of-state grant money instead of pushing for more state funding to pay for more state forensics analysts, agents and attorneys.

In short, Schimel’s critics insist, the attorney general and his staff did not act with a sense of urgency – did not prioritize justice for thousands of sexual assault victims.

That assertion could not be further from the truth, according to DOJ insiders and victims rights advocates who spoke extensively to MacIver News Service.

They say that the initiative Schimel and the Justice Department launched in 2015 has made significant strides. And not just in testing the backlog of rape kits, although that very involved process has been completed. Schimel on Monday announced that all of the outstanding rape kits have been tested.

The Wisconsin Sexual Assault Kit Initiative (WiSAKI) is also changing attitudes, ideas, an entire culture of how law enforcement officials deal with survivors. In fact, the Republican-led DOJ was lauded by the Obama administration for its victim-centered approach to what is a national decades-old problem – a problem, experts say, that is much more complicated than the media investigative reports and partisan press releases like to admit.

“We’ve had a little trouble getting the truth told,” Schimel said of some of the media accounts.

“This problem has been in the making for 20 years and we expect that testing on all of these kits will be done by the end of this year,” Lane Ruhland, DOJ’s director of Government Affairs said. “So we’re talking a 20-year problem solved in three years.”

That’s an important point lost in a lot of the fingerprinting.

Backlog back story

The thousands of backlogged rape kits – sexual assault forensic exams used to preserve DNA evidence that could lead to the arrest and conviction of an offender – extend as far back as the 1990s. That means attorneys general – Democrat and Republican – from Jim Doyle (a Democrat who would go on to serve two terms as governor) to Peg Lautenschlager (a Democrat whose son Josh Kaul is Schimel’s Democrat challenger in the November election) to J.B. Van Hollen – presided over a pileup of rape kits.

The bigger problem, as has been well documented, is that local law enforcement agencies, for various reasons, sat on the forensic evidence or let it collect dust for years. Ultimately, failure to test the kits and submit accused perpetrator DNA into a national DNA tracking database meant sexual predators remained free to assault again.

In December 2012, then-state Attorney General J.B. Van Hollen created the Attorney General Sexual Assault Response Team, made up of a multidisciplinary group of professionals with expertise in the complex issues surrounding sexual assault.

AG SART, as it is known, was in response to growing concerns nationally about a backlog of untested rape kits. An informal DOJ review at the time identified 6,000 untested rape kits statewide. The WiSAKI team under Schimel subsequently did a thorough review and found a total of 6,853 untested kits. After further investigation, 2,695 of the kits were determined to be not designated for testing. In some cases, the victim had not given consent to test the forensic evidence.

Going after grant money

Media accounts have criticized Schimel for going after grant funding instead of asking the Legislature for more money for additional full-time staff to process the untested rape kits. Schimel did suggest hiring more crime lab analysts, but doing so would have been a time-consuming prospect thanks to the usual bureaucratic hoops.

“We looked at the options on how to move forward. It takes months to train a new DNA crime analyst,” said Rebecca Ballweg, the DOJ’s deputy director of communications. More than 18 months to be exact. Analysts must meet rigorous FBI standards. Failure to do so would compromise evidence submission in a court case and, ultimately, prosecutions.

The attorney general did secure a $4 million grant in September 2015 to eliminate the backlog. But the DOJ could not spend a cent of the funding on testing until it had completed an extensive inventory of the untested rape kits statewide. That was a major undertaking.

Delays and bottlenecks

While many law enforcement agencies swiftly responded to the DOJ’s requests, others were slow to answer. In some cases DOJ agents had to drive to local law enforcement offices to collect inventoried kits. They didn’t always find officials available or willing to assist.

In some cases DOJ agents had to drive to local law enforcement offices to collect inventoried kits. They didn’t always find officials available or willing to assist.

To speed up the testing process, the WiSAKI team created a phased approach, moving untested kits through to the next step in the process upon certification. Doing so cleared the bottleneck. Grantors endorsed the system and recommended it for similar projects in other states, Ruhland said.

Also complicating the process was the availability of private labs. While perhaps a sad commentary on the state of society, the fact is sexual assault forensic evidence specialists are extremely busy. In Detroit alone there was a backlog of 10,000 untested rape kits. Schimel said more than 100,000 untested rape kits have been dropped into the system in recent years.

“The huge volume [across the country] of kits just overwhelmed the public and private sector forensic labs,” the attorney general said.“We got it done as fast as possible in the environment we had to work with.”

When the Justice Department sent out its first request for bids, it got no takers. On a second attempt, a private lab committed to take on 3,000 of Wisconsin’s untested kits. DOJ contracted with two other labs to complete the remaining kits.

While there have been fits and starts in the process, Schimel announced on Monday that all of the 4,100-plus kits have been tested.

“Prior to me taking office no attorney general in office ever tested one of these accumulated kits, and in my first term we’ve tested all of them,” Schimel said.

The Wisconsin State Crime Laboratory Bureau must test all of the evidence that comes in from the private labs, in accordance with federal procedures. Then DNA that fits qualifications is entered into the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), the FBI’s program of support for criminal justice DNA databases.

“There is this misunderstanding that we are just sitting on our hands waiting for all of the test results to come in before we start moving forward and that is not the case,” Ruhland said.

‘CSI Effect’

To date, the Wisconsin Department of Justice has pressed sexual assault charges against three suspects thanks to the WiSAKI initiative, including a case in Rock County involving a man already serving time for other sexual assault convictions. The latest charges, filed in June, accuse the convicted sex offender of two counts of sexual assault of a 13-year-old victim in 2000.

Critics scoff at the three charges, asserting there should be more, and would be more if Wisconsin had followed the examples of other states and hired more forensics specialists. Again, DOJ officials say such criticisms are oversimplifications of a complex, long-standing problem.

Chief among the misconceptions is what real-life scientists have described as the CSI Effect. Hit shows such as “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” offer an exaggerated portrayal of forensic science, creating public perception that DNA testing will quickly lead to the conviction of a suspect – within the confines of a 60-minute episode. While academics disagree on the real-life impacts, DOJ officials say the influences of the CSI Effect are real.

Rushing intricate forensic science practices would violate FBI crime lab protocols and ultimately compromise critical evidence and the pursuit of a conviction.

“We deal with that every day,” said Nicole Roehm, director of the Wisconsin State Crime Lab. “We deal with complex science as well as quality control.”

Rushing intricate forensic science practices would violate FBI crime lab protocols and ultimately compromise critical evidence and the pursuit of a conviction.

“The misconception is, ‘Why does it take so long? Can’t you work faster?’ The reason is that you have to hit all the quality benchmarks to make sure all of the results are sound,” said Roehm, who has been with the agency for more than 11 years, the last year as its director. She has been involved in the WiSAKI project from its origins.

There are jurisdictional issues, too. While the state Department of Justice is leading the statewide testing and collection campaign, local police agencies and prosecutors have original jurisdiction in most cases. The WiSAKI campaign has a prosecutor devoted to the sexual assault cases, and the DOJ is a lead partner in the effort. But local timelines for investigation and prosecution do not always follow state law enforcement schedules. Ultimately in most cases, local prosecutors have the final say on whether to pursue charges.

“It’s very frustrating for us when there is so much emphasis put on the kit testing and the idea that it’s not fast enough and it should be done in two weeks,” Ruhland said. “This is a very important piece and we’re doing it very quickly but this project is much bigger and much longer than just the kit-testing portion.”

It’s also about changing attitudes, changing a culture, sexual assault victims advocates say. Not just in law enforcement, but in society at large.

It’s complicated

“This issue and what to do is complicated,” said Ian Henderson, director of legal and systems services for the Wisconsin Coalition Against Sexual Assault (WCASA). “We have to acknowledge that the very fact that we are in this situation is evidence of some system failure, with a variety of reasons why kits are not tested.”

Henderson said law enforcement and society as a whole have learned a lot over the last generation about the treatment of evidence, and of sexual assault victims.

In the early days of DNA collection in particular, law enforcement agencies didn’t always turn in rape kits for testing if they had a suspect. Not doing so failed to recognize what we have come to know: that sexual offenders are often repeat offenders. Data drawn from some 5,000 forgotten and backlogged rape kits in Ohio’s Cuyahoga County found “serial rapists are far more common than previous research suggested…”

There is a greater emphasis on trauma-informed care, and a greater understanding of how trauma can impact a victim. At times investigators have dismissed sexual assault victims, doubting their credibility because of how they remembered events or responded to questions. They didn’t always take into account the role trauma plays in memory or behavior. A trauma-informed approach is changing minds and investigative methods, Henderson and other advocates say.

Years later, victims would learn that their highly personal information was included in some DNA database. They felt victimized all over again.

Law Enforcement officials are also changing the way they handle the collection of physical evidence, thanks in large part to training initiatives and polices created through the DOJ’s Sexual Assault Kit Initiative. Sometimes law enforcement agents would collect rape kits and send them in for processing without the consent of victims. Years later, victims would learn that their highly personal information was included in some DNA database. They felt victimized all over again.

The attorney general’s office has created a third option in what had long been a two-option approach to sexual assault kit collection protocol. Before, most victims could agree or decline to have their kits tested. Now, an “Option C” allows the evidence to be stored for up to 10 years – the statute of limitation on sexual assault charges – at the state crime lab. The lab earlier this month completed a new walk-in freezer that will provide the space to store sexual assault evidence.

The numbers reflect the success of the training and information campaign, Roehm said. In 2017 alone, the crime lab saw a 26 percent increase in sexual assault evidence.

“I don’t believe crimes went up that year, but the awareness and understanding of what DNA technology can be used for did,” the crime lab director said. CODIS, the national DNA database network, has revolutionized sexual assault investigation, perpetually searching for matches that are bringing offenders to justice.

The sexual assault kit itself has been revamped, made to be much less invasive than previous procedures. The state Department of Justice provides the kits free of charge to hospitals.

Changes in practices and attitudes didn’t happen overnight, and they didn’t come without strong partnerships. The Wisconsin Coalition Against Sexual Assault is part of a multi-disciplinary group of victim advocates, law enforcement, health care industry officials and others involved in the initiative since the late 2012 creation of the AG Sexual Assault Response Team. That effort, built on tracking untested sexual assault kits, was launched by Schimel’s predecessor, Attorney General J.B. Van Hollen, also a Republican.

The coalition worked with the DOJ in 2017 to launch a public service campaign and website called By Your Side, a campaign connecting sexual assault survivors to information and resources.

Henderson said the organizations and individuals involved in the initiative, including the attorney general and the DOJ, have made fixing the failures of the past a priority.

Henderson said the organizations and individuals involved in the initiative, including the attorney general and the DOJ, have made fixing the failures of the past a priority.

“We have been at the table along with not only the attorney general, but prosecutors, law enforcement and victims advocates from the beginning. I think that group has made it a priority to address this issue in a way that is as victim-centered as possible, to put into protocols as much victim choice as possible, and to keep victim interests at the center of all of this,” Henderson said.

Contrary to some of the media and political criticism, Roehm said crime lab and DOJ staff are hard-working, dedicated professionals, “passionate about being public servants and taking their love and knowledge of science and applying it for the greater good.”

The hope and the goal, Roehm said, is to make backlogged, forgotten rape kits a thing of the past.

“I don’t think we will have something like this occurring again,” she said.

The DOJ under Schimel has apologized to the victims failed by the criminal justice system for decades.

“Ultimately we took this on voluntarily. I didn’t have to do this, the Legislature didn’t order us to do this. We took on this problem because it was the right thing to do,” Schimel said.

MacIver’s Bill Osmulski contributed to this story.