[bctt tweet=”If school districts saved $3.2 billion on health care and retirement benefits, that money should have been directed to other education programs. #wiright #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”If school districts saved $3.2 billion on health care and retirement benefits, that money should have been directed to other education programs. #wiright #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

A fact check: inflation and spending in Wisconsin public school districts

By Ola Lisowski

October 31, 2018

State spending on school aids has become a major debate across Wisconsin. Many facets of the issue have entered the complicated conversation—including how much money districts receive, how they spend it, and whether the funding formula itself should be changed.

If school districts saved $3.2 billion on health care and retirement benefits, that money should have been directed to other education programs.

A recent Marquette Law poll found that 57 percent of Wisconsinites would favor increasing school spending, with 37 percent of respondents favoring cutting property taxes. That’s quite the swing from early 2013, when 49 percent of respondents said they’d prefer cuts to property taxes, while 46 percent said they’d prefer increasing school spending. Both major candidates in Wisconsin’s heated gubernatorial race have promised to increase state aids and restore the two-thirds state funding commitment for public schools that was established by Gov. Tommy Thompson.

For all of the high-profile debate circulating around the issue, some crucial points have been left out of the discussion. This fact check aims to address those issues to heighten the quality of discourse. Those points center around two concepts: inflation and the 2009 federal stimulus spending.

Inflation

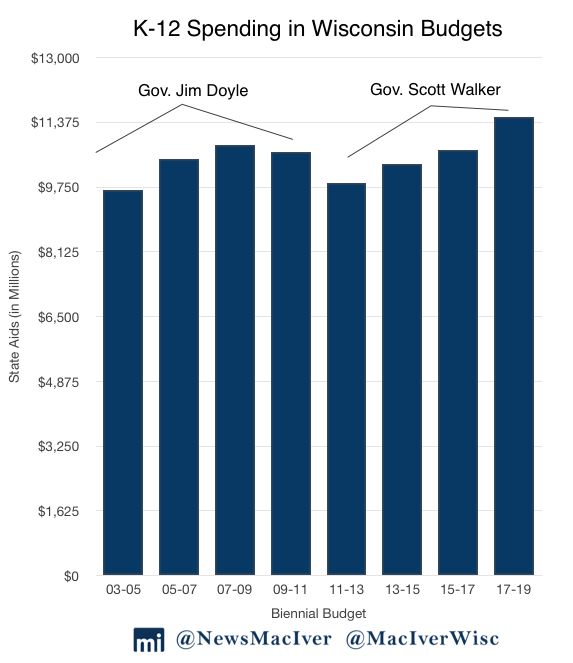

Critics of Gov. Scott Walker have argued that state support to schools has fallen behind since Walker’s tenure began. However, the 2017-19 biennial budget spends more than $11.5 billion on K-12 schools, the largest-ever amount in actual dollars in state history. The current budget increases state aids by $636 million over the prior budget’s investments. Yet when accounting for inflation, budgets from 1997-99 through 2009-11 have outpaced the current spending plan.

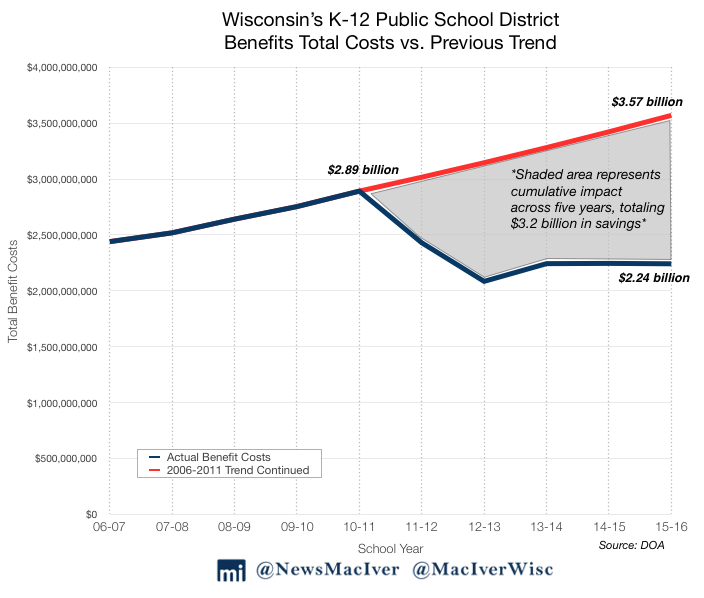

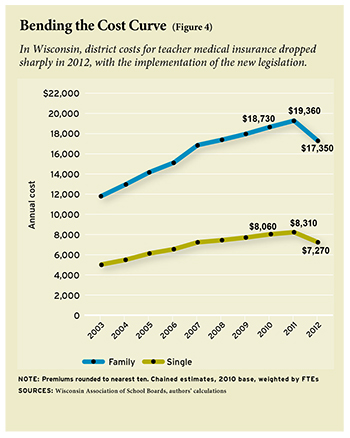

Between 2004 and 2012, school district health insurance costs rose by 4 percent above inflation annually. In Wisconsin, the trend has shifted—thanks in large part to Act 10.

Nevertheless, those measures of inflation do not account for massive cost reductions to public school benefit plans spurred by Act 10. Walker’s public sector collective bargaining reform legislation bent the cost curve for schools and ultimately, for taxpayers. While spending on health care has exploded across the country, Wisconsin bucked the trend because of Act 10.

In the first five years after the law’s implementation, school districts statewide saved a combined $3.2 billion on health care and retirement benefits, according to the Department of Administration. Prior to Act 10, health care spending devoured a significant portion of school district budgets, claiming 4.3 percent increases annually.

Why does this matter? Simply put, if school districts saved $3.2 billion on health care and retirement benefits, that money should have been directed to other education programs.

To understand how dramatic Wisconsin’s turnaround has been, it’s helpful to look outside our borders.

How Wisconsin districts compare nationally on health care spending

Across the country, health care costs have been a significant driver of inflation. At school districts, the line item has eaten up larger portions of budgets over time, outpacing inflation. From 2004 to 2012, school district costs for teachers’ health insurance rose at an annual rate of 4 percent above inflation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Ultimately, high health care spending crowds out spending for other goods and services.

Total health care spending makes up more than 18 percent of GDP – up from just 5 percent in 1960. Almost everywhere you look, spending on health care or health insurance is eating up increasingly larger portions of state budgets.

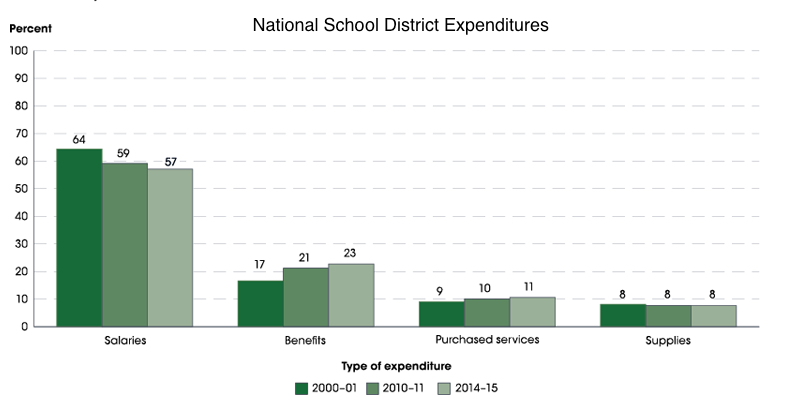

The National Center for Education Statistics — a federal data warehouse in Washington, D.C. — has tracked district expenditures for decades. In the 2000-01 school year, school district employee benefits took up 17 percent of district budgets. Fourteen years later, spending had risen to 23 percent, amounting to a 35 percent increase in just 14 years.

At the same time, spending on school supplies stayed flat. Purchased services increased from 9 to 11 percent, a 22 percent increase. Meanwhile, salary spending fell across the nation. Where salaries took up 64 percent of budgets in 2000, they had fallen to 57 percent in 2014, an 11 percent decline. Together, salaries and benefits make up 81 percent of district budgets. Education spending outside Wisconsin has shifted from salaries to benefits.

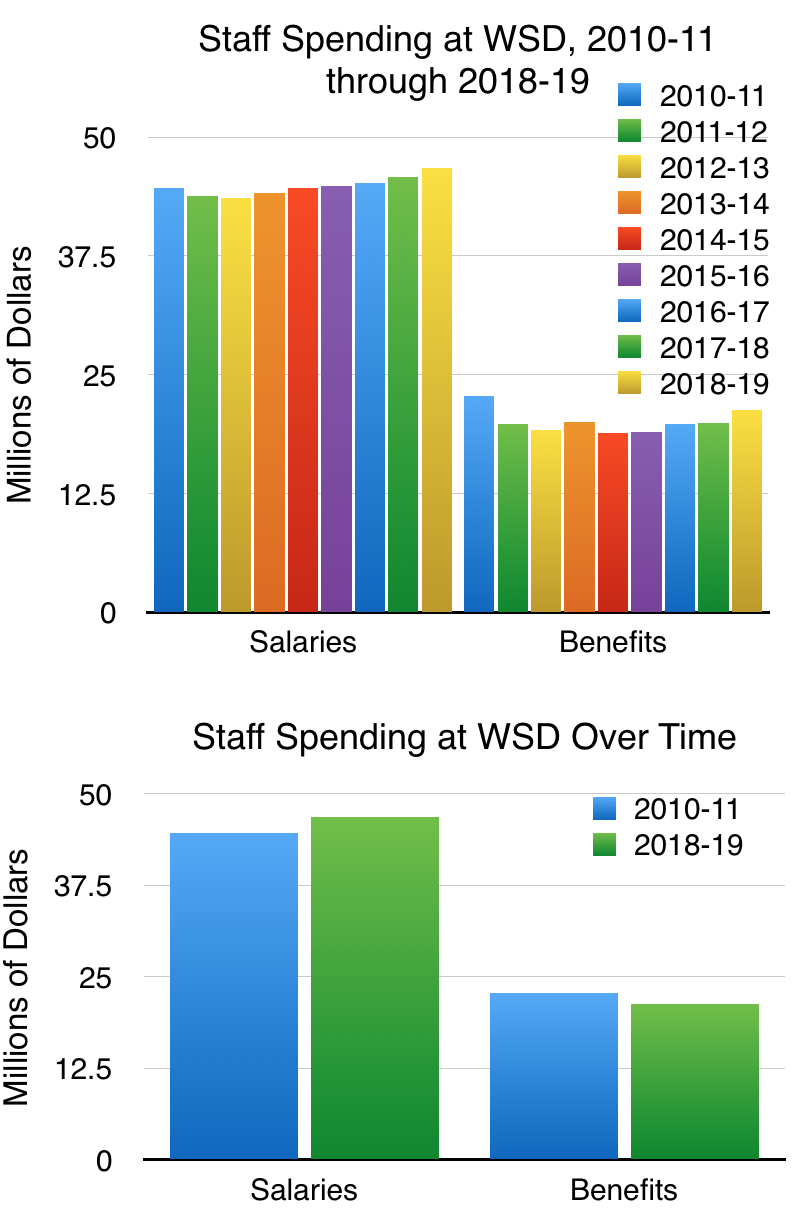

Turning back to Wisconsin, we can see how the trend played out locally, given Act 10’s shift. Take the Wauwatosa School District (WSD), for example. WSD spends less now in actual dollars on benefits than it did in the 2010 school year, which is the earliest available budget on the district’s website. Benefits also take up a smaller share of the overall budget than they used to—23 percent now, compared to 27 percent in 2010.

Since 2001, WSD’s budget has increased by 43 percent. At the same time, enrollment has increased by 2 percent. Overall budget size is slightly outpaced by inflation, which grew by 44 percent in the same time period. Benefits take up a smaller share of the budget, and the district is spending less on benefits than it did in 2010.

In the budgets since 2010, WSD initially decreased its spending on salaries and benefits before slowly increasing them again over time. Personnel is the largest single expense for any business, and schools are no different. These types of cost controls did not occur elsewhere in the country.

Because of Act 10, schools in Wisconsin have largely been able to avoid this cost driver by restructuring their benefits programs and wellness packages, if they so chose. Thanks to property tax controls and Act 10, the biggest driver of district spending has been controlled.

In Milwaukee Public Schools, the state’s largest public school district, business administrators found considerable savings thanks to Act 10. For numerous years, the district and its taxpayers saw falling benefits expenditures thanks to restructuring. The district also paid down its retiree healthcare liabilities, from $2.8 billion to $1 billion today. As MacIver has reported, the district is still in big financial trouble, but without Act 10’s tools, the situation would’ve been much more dire.

That school districts across the state saved more than $3.2 billion in five years alone should be a central part of the conversation on state aids. School districts spend $643 million less on benefits each year. That annual savings is more than the education spending increase in the 2017-19 budget.

As both state and outside estimates show, these reforms bent the cost curve for districts down, and ultimately, for taxpayers.

The federal stimulus

Another facet of the conversation that should be recognized is the role of the 2009 federal stimulus package. MacIver guest columnist Dan O’Donnell recently wrote about that issue here.

Walker’s opponents have long pointed to his first biennial budget, which cut spending to almost every state agency in the midst of a recession and multi-billion-dollar deficit. What Walker’s critics conveniently forget to mention is the fact that state support for K-12 schools was cut by Democrat Gov. Jim Doyle in his last state budget. Instead, those critics add in one-time federal stimulus dollars to the 2009-11 education spending total to make it seem like the governor’s first budget was a bigger cut to education than it really was.

Looking at just state aids to schools, Walker’s 2011-13 budget spent $162.1 million less than Doyle’s 2009-11 budget. A cut, to be sure—but benefits savings to districts since Act 10 have averaged $643 million annually. Those savings far outpace Walker’s first cut to state aids.

Still, by pointing to Doyle’s last budget and contrasting it with Walker’s first, critics miss one critical point: the stimulus.

Stimulus dollars were federal, meaning they don’t show up under state aid—but because so much of the stimulus sent dollars to education, the state cut back its own investment that year without school districts feeling much pressure. In the end, education spending fell by $284 million in Doyle’s last budget. Doyle also terminated the two-thirds state funding commitment to schools.

Supporters of high public funding always knew the stimulus was one-time money. That didn’t stop them from using the figure as a benchmark in the future. Ever since Walker proposed the Budget Repair Bill, followed by the 2011-13 budget, almost any level of spending could be portrayed as a cut. That’s because so much of the total funding in Doyle’s last budget was made up of extra stimulus money.

Walker, who at the time was Milwaukee County Executive, argued that using the temporary federal money would make it harder to balance the state budget in the future, according to a 2009 article. He was right.

As O’Donnell writes, in the second year of Walker’s 2011-13 biennial budget, education spending rose to approximately $400 million more than Doyle had spent if the one-time federal stimulus grant is removed.

To make an honest spending comparison on state aids, one must go back to the 2007-09 budget cycle. To do anything else is to move the goalposts.

State aids to schools are at the highest level of actual dollars in history. When accounting for inflation, those dollars dip below prior year investments when taking a traditional view of state aids as a line item. Yet, not accounted for in that metric is the savings to districts that they can now make, if they choose, through the tools of Act 10. Those savings add up, to the tune of $3.2 billion in just five years.

For the sake of the conversation, let’s use the same benchmarks. Consider that taxpayers’ dollars now go further in the classroom, since public employees contribute slightly more to their own health expenses. Consider, too, that the stimulus package offers a nice federal padding for high spenders to point to.

The state can’t force school districts to reform themselves, which explains why numerous districts still don’t require employees to pay any monthly premiums toward health insurance costs. At the same time, budgets are finite. Taxpayers do not have bottomless wallets – if they did, the population exodus from Illinois wouldn’t be so big. That school districts can now free up more dollars for classrooms is a good thing.

The more prominent an issue becomes, the likelier it is that misinformation spreads. That’s especially true for as complex an issue as school financing. We hope that this fact check helps elevate the debate.