Before a city can create a TIF district, it needs to prove that there’s no other way to generate economic growth in that area. So what happens when Beaver Dam uses TIF to build a business park, and then a private company builds its own business park right next door without using TIF?

A MacIver Report By Bill Osmulski

“If you build it, he will come.”

That’s what Kevin Costner believed in the movie, Field of Dreams, when he plowed over his corn field to build a baseball park. That’s also basically what cities across Wisconsin believe when they build business parks using “tax incremental financing” or TIF.

Costner’s fantasy ended with the spirits of baseball’s greatest players from the great beyond bounding out of the corn to play on the Iowa diamond, while thousands of tourists lined up to buy tickets. The TIF fantasy ends with business appearing out of nowhere to buy lots and create jobs.

Costner took an enormous risk in the movie. His family needed that cornfield to generate their income. Likewise, cities take an enormous risk when they borrow millions of dollars on the hope that new economic growth will generate enough in new property taxes to pay it back.

Beaver Dam, for example, borrowed $2.24 million to buy 214 acres along US Highway 151 in 2011. Five years later the city designated that land as Tax Increment District (TID) #7, and committed another $19.9 million in estimated project costs to build a business park. It then sold three of the lots (a total of 42 acres) for $3. That brought in its first three businesses. The city awarded one of those businesses an additional $1 million in 2017. That’s a lot of money upfront.

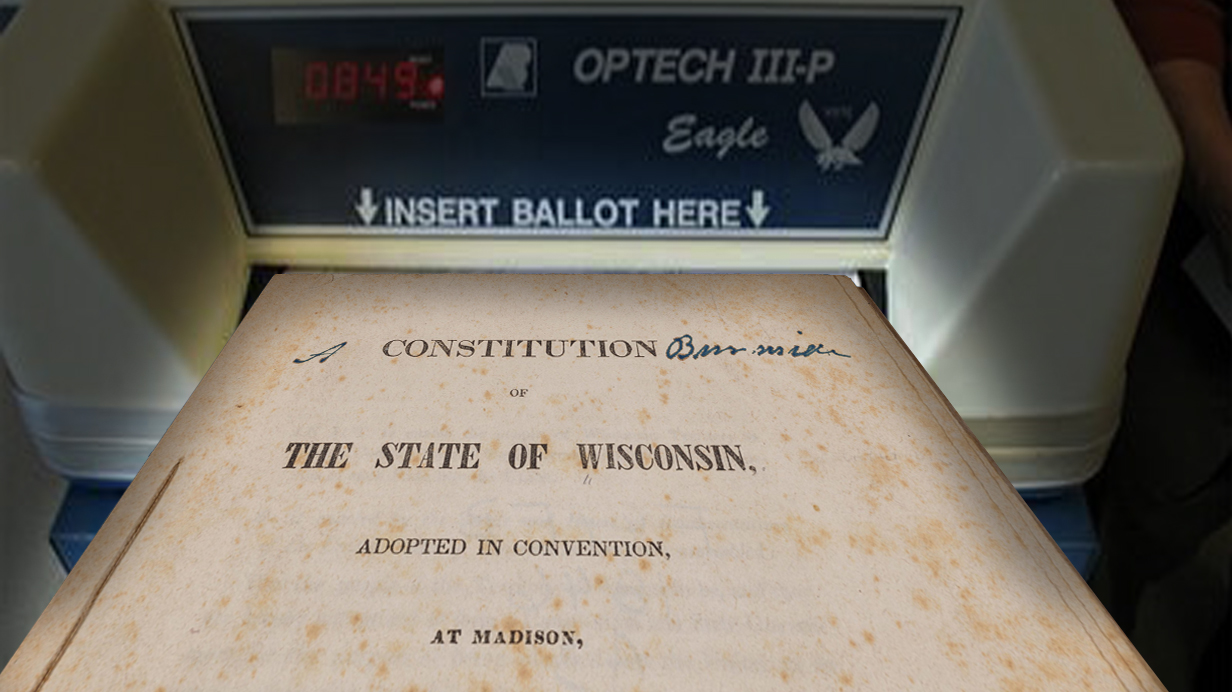

The TIF process is, of course, heavily regulated – on paper that is. For one of the requirements, the local government must prove that no new businesses would appear unless it creates the TIF district. This is called the “but-for” provision. It’s impossible to prove, but fortunately for local governments, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in July that the local governments get to decide for themselves whether or not they meet the requirement. In other words, “but-for” is just a formality. That’s a good thing for Beaver Dam.

This past summer Alliant Energy announced it was building its own 520-acre business park (entirely with private funds) a mere 800 feet away from Beaver Dam’s business park. Obviously that calls into question the city’s “but-for” claim on why it’s spending over $20 million of public funds on its business park. What’s worse is Alliant Energy’s philosophy is the complete opposite of Beaver Dam’s.

Build it, if they come.

Scott Reigstad, Alliant Energy Senior Communications Partner, explained “If a business or businesses decide to locate in the park, the plan would be for the city of Beaver Dam to annex the property. Then, we would expect the city to serve the site with normal city services like water and sewer as well as general infrastructure like roads.”

If this plan is successful, Alliant has a lot to gain. The lots are sized for big industrial customers, which coincidentally have large energy requirements. A decent sized factory can easily spend a million dollars a month for electricity. At the same time, Alliant is taking practically no risks. It didn’t buy the land outright – it’s on a five-year option contingent on attracting customers to the site. All they’re on the hook for right now is the marketing campaign.

Not only is Alliant taking much less risk, if it succeeds the payout will be immediate.

Beaver Dam’s residents, on the other hand, could be waiting a long time before they benefit from the city’s field of dreams. None of the new property taxes from businesses in TID#7 can go into the general fund until all the project costs are paid back and the TID closes, which might not happen until 2036. That’s a lot longer than Kevin Costner had to wait, but probably just as risky.