[bctt tweet=”In his latest column, @DanODonnellShow outlines serious Constitutional issues with the “red flag law” Wisconsin’s new Attorney General has proposed. #wiright #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”In his latest column, @DanODonnellShow outlines serious Constitutional issues with the “red flag law” Wisconsin’s new Attorney General has proposed. #wiright #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

January 16, 2019

Special Guest Perspective by Dan O’Donnell

There is perhaps no more significant power of government than its power to imprison individual citizens and deprive them of their personal property, and thus there should be no power more closely scrutinized.

Under a red flag law, a family member may request that a judge confiscate an individual’s firearm based on the mere suspicion that he is mentally unfit to own one.

It’s fitting, then, that a new proposal to seize property is termed a “red flag law” since it raises so many red flags.

Wisconsin’s new Attorney General Josh Kaul proposed such legislation in his inaugural address, calling for the passage of a bill “that will allow law enforcement or family members to go before a judge and ensure that someone who is a threat to themselves or others is temporarily disarmed.”

Governor Evers signaled support for this, as did Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, who cautioned that while he is “open to the idea,” he is concerned about “the scope being too broad.”

That may be an understatement.

Red flag laws, which have been passed in six states—most recently in Florida last year—pose substantial risks to both Fourth and Fifth Amendment rights (to say nothing of Second Amendment rights), as they allow for the confiscation of firearms without the protection of due process as it has been traditionally understood.

The Fourth Amendment provides that “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause.”

Probable cause generally exists only when “there is a reasonable basis that a crime may have been committed (for an arrest) or when evidence of the crime is present in the place to be searched (for a search).”

Under a red flag law, however, a family member may request that a judge confiscate an individual’s firearm based on the mere suspicion that he is mentally unfit to own one. Even if there is no evidence that a crime has been committed or is even likely to be committed, the judge can order guns seized.

Even more troublingly, the subject of the seizure might not have an opportunity to defend himself or even know of the allegations against him until law enforcement officers show up at his door to confiscate his weapons.

This Kafkaesque nightmare isn’t just an overwrought hypothetical; it’s actually happening.

Just two months after Florida passed a red flag law in the wake of the Parkland shooting, Broward County Sheriff’s Department bailiff Frank Joseph Pinter was accused of making threatening remarks to a colleague that allegedly included “all you rats should be exterminated.”

Six months earlier, The Orlando Sun-Sentinel reported, Pinter was spotted leaning over a courthouse atrium and pretending to shoot at people below him. Another bailiff accused Pinter of saying to him, “I’m going to exterminate you.”

In May, the Sheriff’s Department had had enough from what it deemed to be a dangerous employee and sought what is known as a “risk protection order” under Florida’s new law. Without granting Pinter an opportunity to defend himself or explain his conduct in court, a judge determined that “there is reasonable cause to believe the respondent poses a significant danger of causing personal injury to himself or others in the near future” and ordered his guns to be confiscated.

When the only standard for seizure of property is a vague determination of risk to self or others based on evidence presented only by those who are seeking to seize property, what chance does the individual possibly have of keeping said property?

That afternoon, deputies took all of Pinter’s guns, ammunition, and even his concealed carry permit. He had no idea that there had been a judgement against him (or even that an action had been filed against him) until his guns were being confiscated.

Needless to say, this is antithetical to constitutional protections against what is rather obviously an unreasonable seizure. Pinter may well have been mentally disturbed, but there was no probable cause that he had committed a crime that would warrant government repossession of his personal property.

That he was not offered a chance to defend himself against the allegations against him compounds the issue by presenting a rather clear violation of Pinter’s Fifth Amendment right to protection against deprivation “of…property, without due process of law.”

When the only standard for seizure of property is a vague determination of risk to self or others based on evidence presented only by those who are seeking to seize property, what chance does the individual possibly have of keeping said property?

And what chance does he have if he doesn’t know an adjudicative proceeding against him is taking place?

Under Florida’s red flag law, Pinter was finally afforded the opportunity to challenge the seizure of his weapons several weeks after they had been seized. Only then—weeks after punitive action was taken against him—was he allowed to defend himself against the allegations that led to that punitive action.

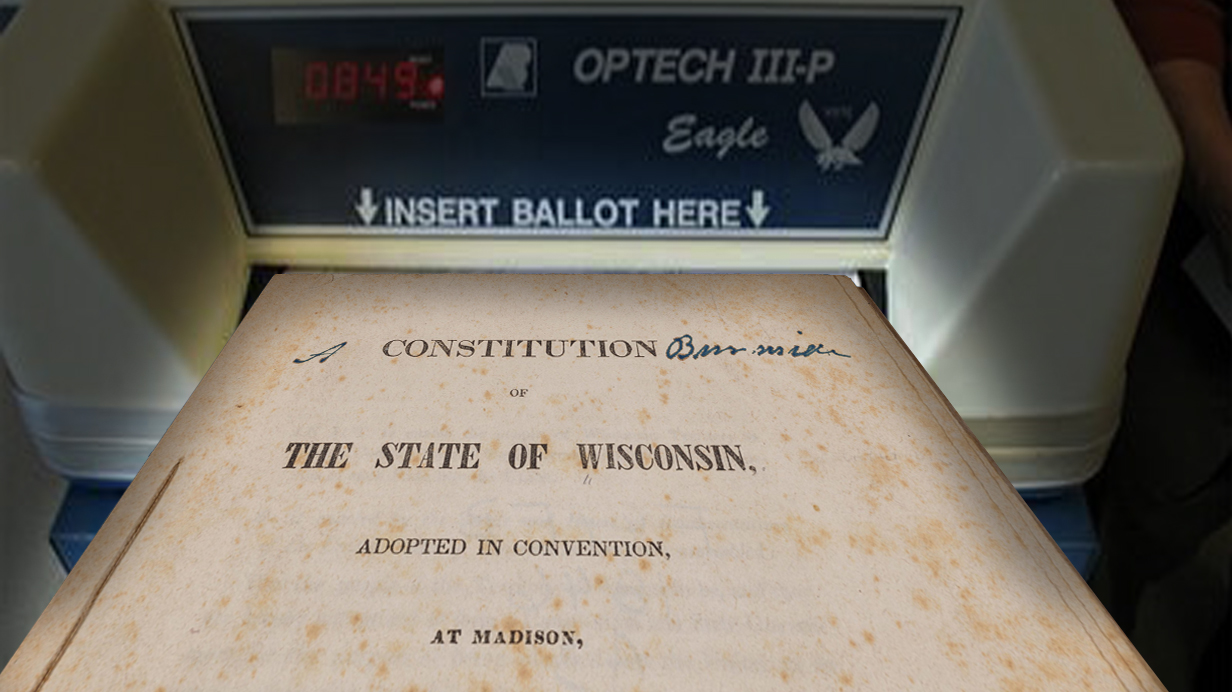

Now Wisconsin’s Attorney General and Governor are proposing a nearly identical law, apparently unbothered by the radical infringements on individual civil liberties. The stated end—ostensibly lowering gun deaths—is a noble one, but even it cannot justify such unconstitutional means.

Quite simply, the power of government to seize property—even potentially dangerous property like firearms—is too significant to leave citizens—even potentially unstable ones—unprotected.