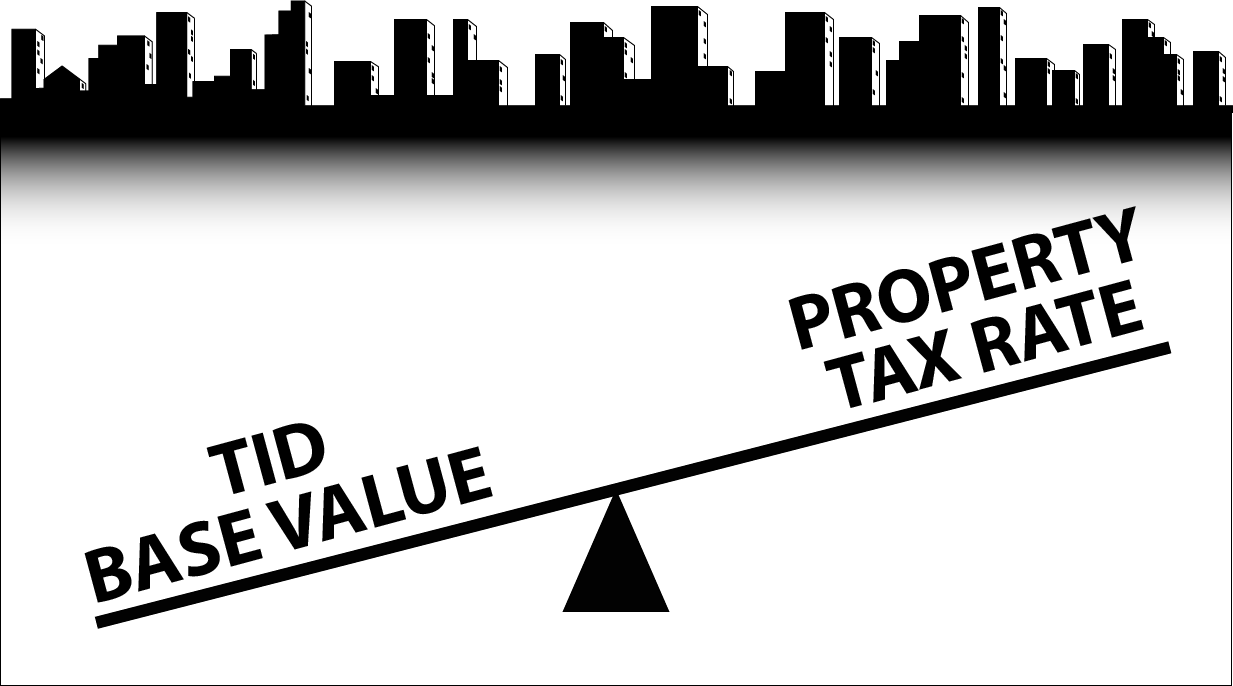

Lowering the base value of a Tax Increment District can increase its revenue, but it also raises property tax rates throughout a community. It happens all the time.

A report by Bill Osmulski

A city’s tax levy is not affected when property values go up or down. A Tax Increment District’s (TID) revenue, however, is affected by higher or lower property values. Therefore, if a city can shift some of its property value into the TID, the tax levy will stay the same, but the TID will make more money…Oh, and everyone will be paying higher property taxes to make up the difference. That’s why a TID’s “base value” is so important.

When a TID is created, all the property that currently exists there is still required to pay property taxes for the city’s levy. The value of the property at the time the TID is created is called the “base value.” Any increase in property value afterwards creates revenue for the TID, called the “tax increment.”

There are plenty of tricks to artificially lower the base value, which give the TID’s revenue a boost while increasing the community’s overall tax burden.

Buy the Land First

Government-owned property is not taxed, which means it is assessed at zero dollars. When governments purchase land first and then turn it into a TID, the base value is set at zero. As soon as that land is sold, its actual worth is revealed and creates an impressive tax increment even before any development takes place.

One TID in Chippewa Falls went from an assessed value of $0 in 2015 to $59 million in 2018. A TID in Beaver Dam went from $0 in 2016 to $21 million in 2018. Another TID in Milwaukee went from $0 in 2017 to $2.2 million in 2018. There are currently 22 TIDs around the state using this technique.

Incorrect Zoning

It’s not location, location, location that determines a property’s value. It’s zoning, zoning, zoning. Case in point, Muskego had 10 acres of real estate right in the heart of its downtown valued at only $2,400, because it was zoned agricultural. The plan for a TID was created, and a developer bought the property for $3 million. The city kept it zoned agricultural for another year, and set the TID’s base value at $2,400. Afterwards, it rezoned the land as commercial, and its new value (without improvements) jumped to $4.5 million. Had the rezoning occurred before the TID was created, residents would have received about $80,000 in tax relief annually, but that instead goes into the TID’s coffers.

Resetting the Value

TID’s don’t always turn a profit. That’s a big problem since it’s used to pay off the debt for the project costs. Fortunately for local governments, they can create an artificial profit by lowering the base value. That requires permission from the Department of Revenue, but it’s not uncommon. The Village of Twin Lakes reset the value of its TID#1 from $53.1 million to $44 million in 2016. After removing $9.1 million from the tax rolls, the city’s tax rate jumped from $4.99 to $5.17 to make up the difference.

Whether directly or indirectly, immediate or deferred, drastic or negligible – the relationship is always the same. Anytime you shift property value into a TID, property tax rates will be higher as a result.