March 29, 2019

A MacIver Analysis by Bill Osmulski

Tax increment financing, or TIF, has built an incredible reputation in Wisconsin when it comes to local economic development. Sen. Rick Gudex summed it up in a 2015 memo, “TIF is the only tool that Cities, Villages, and Townships have for economic development across the state on a local level.”

TIF certainly is popular. In 2018, there were 1,261 active TIF districts in Wisconsin worth a combined $20.9 billion, up from 1,151 in 2014 worth $16.2 billion. That’s a 29 percent increase in value just over four years. However, that alone doesn’t prove Gudex’s statement that local governments needed TIF in order to facilitate that growth.

In fact, after close examination, there appears to be very little local government can accomplish with TIF that it cannot accomplish without it. Clearly this tool creates certain beneficiaries who are happy to promote misleading statements about TIF and its impacts on a community. Unfortunately, taxpayers are not often among those beneficiaries.

The goal of this paper is to provide a cohesive explanation of how TIF impacts local taxpayers with targeted analysis and specific examples, and uncover who benefits from its use.

Bonding Basics

The process of tax increment financing is very complicated, but the concept is quite simple. A local government creates a special district (a tax increment district, or TID) where it will fund improvement projects using bonds. It will eventually pay back the bonds using property taxes from future economic development in that district.

A local government does not have access to more money just because it is using TIF.

Typically, when borrowing money for a project, local governments have two main options: general obligation bonds (GO) or revenue bonds. GO bonds are regulated by state statute because taxpayers are ultimately responsible for paying them back. A municipality can borrow 5 percent of its total property value using GO bonds. Local governments can collect property taxes above and beyond their levy limit to make the debt service payments on GO bonds. Revenue bonds, on the other hand, are not regulated or even tracked by the state because taxpayers are not legally responsible for them. Project revenues are supposed to pay them back, and there’s no limit on how much a municipality can borrow using revenue bonds.

When borrowing for a TIF project – the same bonding methods are used and the exact same rules still apply. If GO bonds are used in a TID, the municipality is still limited to 5 percent of its total property value. If revenue bonds are used in a TID, the project is still expected to produce the revenue to repay them. In other words, a local government does not have access to more money just because it is using TIF. So why use TIF at all? Supposedly, it’s about equality.

Origins of TIF

When the State of Wisconsin created its TIF statute in 1975, lawmakers argued that it was unfair for a single municipality to pay for a public works project, when everyone in the surrounding area would benefit from it. When it spurred economic growth, all the overlapping taxing districts would see increases in property tax collections. The TIF law fixed that “inequitable” situation, by denying overlapping districts (i.e. school districts and counties) any additional property tax revenue from new developments within the TID until all the project costs are paid back and the TID closes.

Savvy local governments learned that TIF allows them to essentially double tax the community for development inside the TID.

That was the whole rationale for creating the TIF law – to force school districts, counties, and other overlapping taxing districts to contribute to projects that would benefit all of them. Unfortunately, this concept completely ignored the taxpayer – who, individually, was paying taxes to all those units of governments at the same time. There were other oversights that hurt taxpayers, too.

Savvy local governments learned that TIF allows them to essentially double tax the community for development inside the TID. To understand how they do this, we need to briefly explain how property taxes are levied in Wisconsin.

Rising Levies or Reduced Services

In 2005, the State of Wisconsin locked local governments into their existing base levies at that time. Although local governments can go over the limit to collect debt service payments, there’s only one factor that allows them to increase their levy without going to referendum – net new construction. The base levy (or levy limit) increases by the percentage of net new construction each year. Most local governments, not surprisingly, choose to set their levy as high as their levy limit allows or, in other words, they opt to “tax to the max.”

TID property owners pay back their debt, while their share of the local tax levy is paid by everyone else.

After the levy is set, the tax rate gets calculated. That’s done through dividing the levy by all the taxable property in the community. If the tax levy increases and the total property value increases at the same pace, the tax rate does not change. If the levy increases more than property values do, the tax rate increases. If the property values increase more than the levy does, the tax rate decreases.

TIFs disrupt this process and lead to higher property taxes in communities that “tax to the max.” That’s because all net new construction – including net new construction within a TID – raises the base levy. However, when the tax rate is calculated, the new property value in the TID is left out. And when the levy increases more than property values, tax rates go up. If such development took place outside a TID, tax rates could easily remain flat.

New property value created in a TID is called the “value increment.” Even though it is left out of the tax rate equation, the municipality still collects property taxes from it at the same rate everyone outside the TID pays. This is called the “tax increment.” This revenue does not go into the local general fund. It is used to pay back the bonds that funded the TIF project costs. The reality of this is TID property owners pay back their debt, while their share of the local tax levy is paid by everyone else. So much for “equitable” cost sharing.

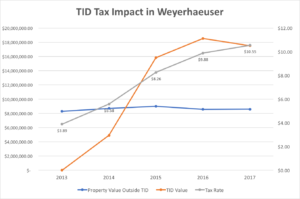

The Village of Weyerhaeuser is a great of example of this concept in practice and its potentially devastating impact on local taxes.

The village created its first TID in 2014. Since 2013, the village’s total property value outside the TID has increased by only 3.6%, from $8.3 million to $8.6 million. Meanwhile, Weyerhaeuser’s local tax revenue has grown 132%, from $39,432 to $91,312. The local property tax has exploded from $3.89 per thousand dollars of property value to $10.55 – a 171% tax hike.

The reason for the massive property tax increase is that almost all of Weyerhaeuser’s net new construction has occurred within its TID. In the span of just three years, Weyerhaeuser’s tax increment grew from nothing to $17.5 million. All that growth led to the village’s base levy increase, and village officials opted to “tax to the max.” The levy might have risen, but property values outside the TID stayed somewhat static – and so the mill rate shot up.

This same scenario plays out beyond the municipality and affects everyone in the county. That’s because the net new construction in the TID also raises the county’s base levy. Ultimately taxpayers throughout the entire county can see higher tax rates because one municipality decided to create a TID.

Whenever new development takes place in a TID, that community will experience either higher taxes or reduced services.

If local governments decide not to raise their tax levy due to net new construction in TIDs, another problem arises. Those new developments require public services like police, fire, and ambulance. Streets need to be plowed. Street lights need electricity. If the tax levy isn’t increased to pay for this, local governments will have to stretch their existing budgets to fit these new requirements. So whenever new development takes place in a TID, that community will experience either higher taxes or reduced services. There’s no getting around that.

The Many Allures of TIF

Municipalities are required to close a TID as soon as its projects’ costs are paid off, or it has been open for 20 years. However, there are ways around that. Any TID can be extended for three years. TIDs created before October 1995 can stay open for 27 years, and those created before October 2004 can stay open 23 years. Blighted TIDs can also stay open for 27 years plus the three-year optional extension. Additionally, at least 60 municipalities have secured personalized carve-outs in the state’s TIF law, which has subsequently ballooned to 26,000 words. The law was only 4,560 words when it was first passed in 1975. Using these techniques, municipalities across the state have managed to keep TIDs open far beyond their original life expectancies.

The most extreme case of this is in Kenosha. The city created TID #1 forty years ago in 1979. It is currently scheduled to expire in Sept. 2021, which would give it a total life of 42 years. Another TID in Kenosha, TID #4, is also projected to have a 42-year life, from 1989 to 2031. If both of those TIDs were to close today, $155 million would be added to the city’s total taxable property value, resulting in a noticeable drop in property taxes. That’s always the promise to local taxpayers when a TID is created, that the day the TID closes, property taxes will drop. However, as Kenosha demonstrates, that day might never come. The problem is not limited to Kenosha. Throughout the state there are another 25 TIDs currently projected to have a 40-year existence.

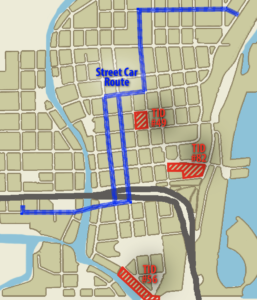

There are many reasons why municipalities try to maximize the life of a productive TID. A big one is local officials can use that revenue to fund other projects in the TID or “donate” it to another TID in the municipality. TIDs are allowed to stay open for the sole reason of allocating their tax incremental revenue to another TID, which is why Kenosha’s TID #1 has been kept open for so long. This becomes a slush fund of sorts, because the TID is now funding local officials’ pet projects rather than contributing to the general revenue tax base. The City of Milwaukee has 3 TIDs paying a combined $59 million for the mayor’s streetcar project, which doesn’t run through any of them.

Lack of transparency is another reason that makes TIF attractive to some public officials. TIF project expenses are rarely identified in municipal operating or capital budgets. For example, although the Milwaukee streetcar has so far cost taxpayers $59 million, there is not a single cost associated with it in the city’s operating or capital budget. TIDs are only mentioned in Milwaukee’s budget to record their combined collected tax increments in the context of debt service. There is no indication of how much money they spent or what it was for.

Such concealment facilitates expenses that many taxpayers would find distasteful – like direct subsidies to corporations. It’s very common for municipalities to offer grants or forgivable loans to private companies for building facilities in a TID.

For example, TID #62 in Milwaukee has a $1.87 million project plan, and $1.5 million of it is going to DRS Technologies to help pay for an $11.5 million expansion project. The company employed 544 employees in 2017, and it will not have to repay the $1.5 million as long as it kept employment above 450 through the end of 2018. Not only is it a sure bet for the company, it’s proven to be a poor investment for the city. The project is complete and the TID has only increased in value by $1.4 million, a $470,000 loss from the $1.87 million investment.

Another direct payment from a TID to a private company happened in 2017. The City of Milwaukee gave Bon-Ton (Boston Store) a $1.9 million forgivable loan from TID #37 when the company promised to keep its corporate offices in the Grand Avenue Mall for the next ten years. Less than a year later, Bon-Ton went out of business and was liquidated. Milwaukee taxpayers will never see that $1.9 million again.

Such underwhelming results are rampant with TIF. Another common example are business parks, which can be found in practically every city and village in the state – usually in a TID.

Edgerton established its business park in 1998, expecting it to generate a $785,264 tax increment by 2016. In 2012, it re-estimated that to $456,730. When 2016 was finally in the books, the tax increment only amounted to $358,928. The park proved to be a bust in attracting tenants. After the first 15 years, it only had three businesses in the 93-acre park, with 42 acres still vacant. The city owned 18.5 of those acres and then bought the other 23.4 acres from the developer. It then slashed the price from $29,900 to $19,900 per acre. It didn’t work. Years later there are still only three tenants.

“But-For” Buts

Business parks also help illustrate another shifty practice in TIF. Before a municipality can create a TID, state statute requires it to determine the desired economic result would not happen “but-for” using TIF. Unfortunately, that provision is enforced with the honor system, and local governments get to decide for themselves exactly what “but-for” means.

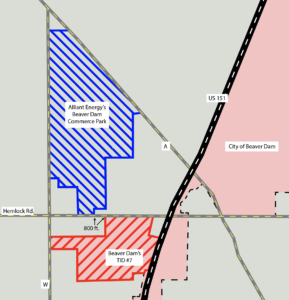

And so, we come to the City of Beaver Dam. It created TID #7 in 2016 to build a 200-acre industrial park along USH 151. The project plan’s estimated cost was $19.9 million. The city determined “The development described in the Project Plan would not occur without the creation of TID #7.”

That proved to be a cringe-worthy statement when Alliant Energy created its own 500-acre industrial park two years later about 800 feet away without resorting to TIF. According to Alliant, “a favorable business climate, quality workforce and a robust retail marketplace are factors driving industry growth in the community.” That is to say – not government incentives.

Alliant’s strategy is not “if you build it, they will come.” It’s more like “build it if they come.” Once a company decides to move into the park, Alliant will request annexation for that lot into the City of Beaver Dam. The city will then be expected to provide the necessary services and infrastructure to support it. This flies in the face of the justification given for every single TIF project in state history.

There’s something to be said for Alliant’s approach given how often TIFs fail to deliver and the consequences when that happens. In 2008, the real estate market crashed, and about 80 TIDs around Wisconsin found themselves at risk of defaulting on their bond payments. The League of Wisconsin Municipalities warned state lawmakers that the situation was unprecedented and “a default would increase the future cost of credit for all municipalities, may make credit entirely unavailable for some communities, could stifle future economic development, and would lead to protracted and costly litigation for the parties directly involved.” Although that did not happen, the threat remains – yet the League of Wisconsin Municipalities continues to push TIF as its go-to economic panacea.

TIFs in Trouble

In response, the state legislature created the “distressed TID” and “severely distressed TID” designations. It allowed municipalities to extend the maximum life of those TIDs so they would have more time to pay back the bonds.

That law was essentially a “one-time offer.” It only applied to TIDs created before October 1, 2008 and no TID could be added to the distressed/severely distressed list after September 30, 2015. Even though that deadline is long past, many TIDs still find themselves in dire financial situations.

Out of 2,558 TIDs across Wisconsin in 2018, 407 of them (16 percent) lost value since 2017. The state created another option for troubled TIDs in 2014 that is still in effect today. If a TID loses value two years in a row and its current value is at least 10 percent lower than its base value, it is eligible for “base value redetermination.” That means the state will retroactively lower the original value of the TID in order to artificially create a tax increment. When that happens, the total property value outside of the TID drops suddenly due to the loss of the TID’s base value. However, the levy remains the same, which leads to a higher tax rate throughout the community.

The Village of Twin Lakes was one of the first municipalities to exercise this base value reset. It established TID #1 in 2007 with a base value of $53.1 million. Despite the economic downturn, it still managed to generate an increment for the first three years, but after that it declined dramatically. In 2014, it lost over $9 million in value. A financial analysis predicted it would never generate a tax increment again, yet it still owed $2.8 million in project costs. The village began exploring the possibility of resetting its base value. In 2016, the state agreed to drop the TID’s base value from $53.1 million to $44 million. That created an immediate positive increment of $3.4 million for the TID, but it also meant a jump in property taxes from $4.99 to $5.17 per thousand dollars of property value.

So far, only six TIDs across the state have used this option, but the state continues to build off the concept. In 2017, it created a special kind of TID called an “environmental remediation” (ER) TID. Municipalities can create an ER TID when at least 50 percent of a designated area is polluted. After the ER TID is created, the base value is automatically set at $1. No ER TIDs have yet been created under the new law.

Tricking TIF

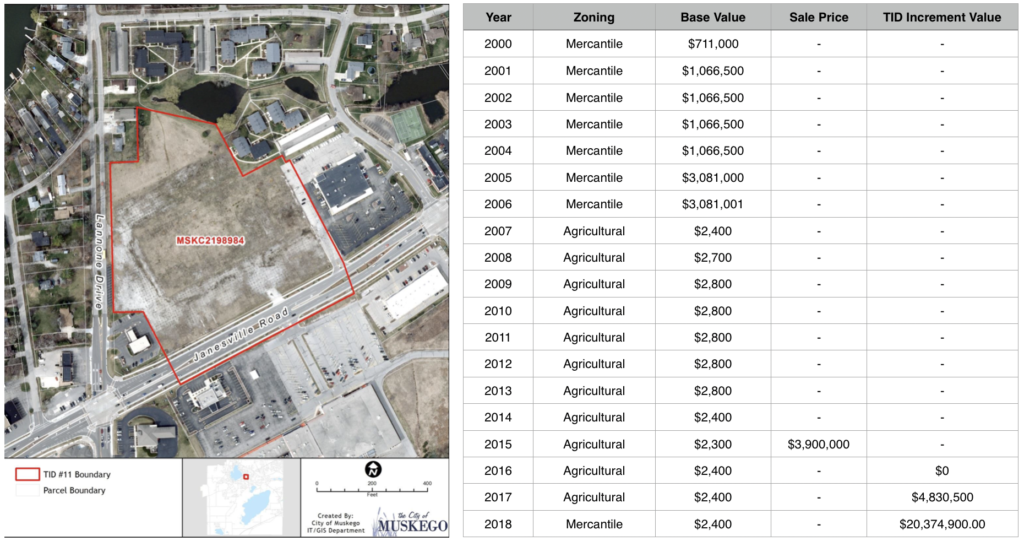

Municipalities also sometimes choose to preemptively reset a TID’s value, which artificially inflates its tax increment from day one. Muskego’s controversial TID #11 is an interesting example of this scenario. The TID is comprised of 10 acres of prime real estate right in the heart of the city’s commercial district. It used to be the site of a shopping mall, which was torn down in 1998. The lot remained vacant for years, but its value continued to climb. By 2006, it was worth $3 million. The next year it was rezoned agricultural and was reassessed at $2,400 for the entire 10-acre lot. Eventually, a developer bought it in 2015 for $3.9 million, yet it was still assessed as agriculture for the next two years. Meanwhile, the TID was created in 2016 with a base value of only $2,400. By 2018, that had grown by a mindboggling 849,054% to $20.4 million. What the city will do with the revenue from that increment is anyone’s guess, since its other three TIDs are doing just fine on their own. Had the city been honest about assessing the base value of the TID, property owners throughout the community would have enjoyed a lower mill rate, with no negative impact to the TID’s viability. Instead, the city decided to jump start a new slush fund.

Terminating TIF

Eventually, all TIDs will presumably close (even in Kenosha) and taxpayers will take one last hit. State law allows local governments to increase their base levy by 50 percent of the tax increment when it terminates a TID. Remember, the net new construction within the TID already increased the local levy limit. The 50 percent bump is in addition to that – meaning development inside a TID is good for an eventual 150 percent increase in the base levy. Subsequently, the termination of a TID does not always result in a tax decrease. Sometimes it has the opposite effect.

The City of Cornell was one of five municipalities to become TID-free in 2017. Its TID had a value of $1.36 million at the time it was terminated, and the city had a total value of $63 million. Even though the city only had a net new construction percentage of 0.53 percent, the tax levy jumped 20 percent. The local mill rate went from $6.68 to $7.80. Part of that would have gone to pay off the TID’s final $24,700 in debt. The rest is the impact from the final-50 percent rule. There’s no other way Cornell would have been allowed to raise its levy.

Reforming TIF

With so many abuses and shortcomings, the Legislative has its job cut out for it. Unfortunately, most recent actions taken by Wisconsin lawmakers regarding TIF have been to reduce restrictions and promote increased use.

The 12 percent rule is a frequent target of legislation. Currently, a municipality is not allowed to create a new TID if more than 12 percent of its total equalized value is already contained in TIDs. A bill in 2015 sought to increase that limit to 15 percent. It had wide bipartisan support but failed to pass before the session ended. In response, lawmakers simply provide exemptions on a case-by-case basis. In fact, the very first bill signed into law in the 2017 session was an exemption allowing the Village of Oostburg to go up to 15 percent.

Other bills that have become law in recent years made it easier to transfer funds between TIDs, obtain a five-year extension on maximum TID life, and relaxed the standards for what kinds of property can be in a TID.

One bill that actually increased oversight was 2015 Assembly Bill 132/Senate Bill 51. It required every TID to file an annual report with the state Department of Revenue that includes anticipated termination date, developers’ names, itemized expenses, the fund balance and tax increments collected. Still there’s much more lawmakers can do to protect taxpayers.

First of all, the state needs to start enforcing TIF requirements. When every municipality can create its own individual definition of “but-for” and “blighted,” there’s no point in making them requirements in the first place. Also, exemptions to the rules are far too common. When lawmakers are willing to provide a custom exemption for any community that asks for one, what exactly is ensuring communities behave responsibly with TIF?

Lawmakers should prohibit municipalities from raising their base levy for net new construction in a TID until it is terminated and eliminate the bonus 50 percent altogether.

The best thing the legislature could do to protect taxpayers from TIF involves net new construction. Right now, local governments get to raise their base levy when net new construction occurs within a TID, and then they get to raise their base levy another 50 percent of that when the TID is terminated. Lawmakers should prohibit municipalities from raising their base levy for net new construction in a TID until it is terminated and eliminate the bonus 50 percent altogether.

Last Word

As evidenced from the many examples above, TIF too often results in higher property taxes in the name of economic development. That development is never guaranteed and is not always contingent on the use of TIF in the first place. Furthermore, many public works projects currently funded through TIF could just as easily be funded with non-TIF bonding. This all runs contrary to popular narratives concerning TIF, and serves to demonstrate the great need for reforms.