[bctt tweet=”The gas tax might be off the table, but that doesn’t mean the debate over road funding is over. In this analysis, we describe many simple reforms that could save money while fixing local roads. #wibudget #wipolitics #wiright ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”The gas tax might be off the table, but that doesn’t mean the debate over road funding is over. In this analysis, we describe many simple reforms that could save money while fixing local roads. #wibudget #wipolitics #wiright ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

June 5, 2019

By Bill Osmulski

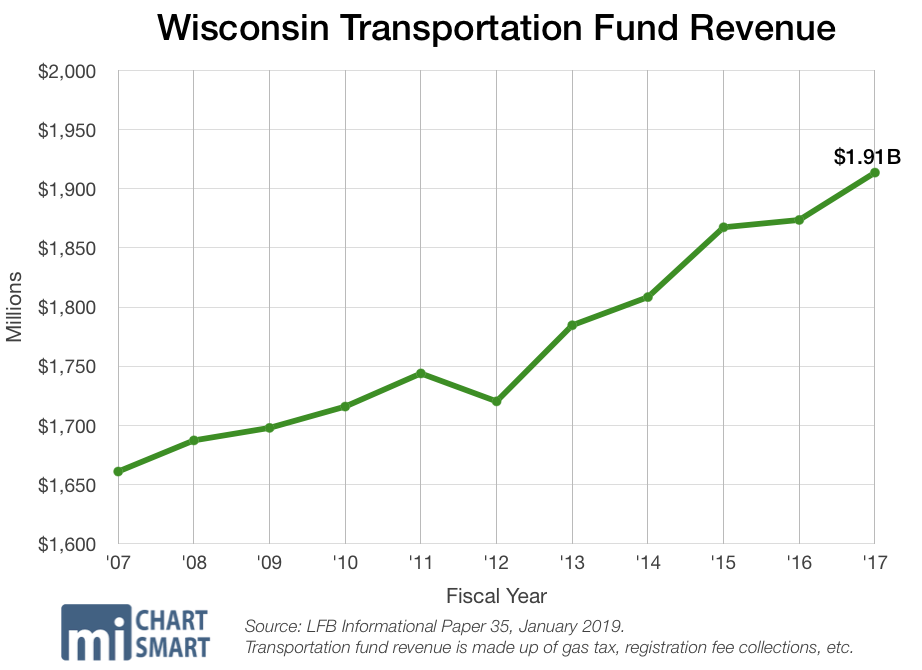

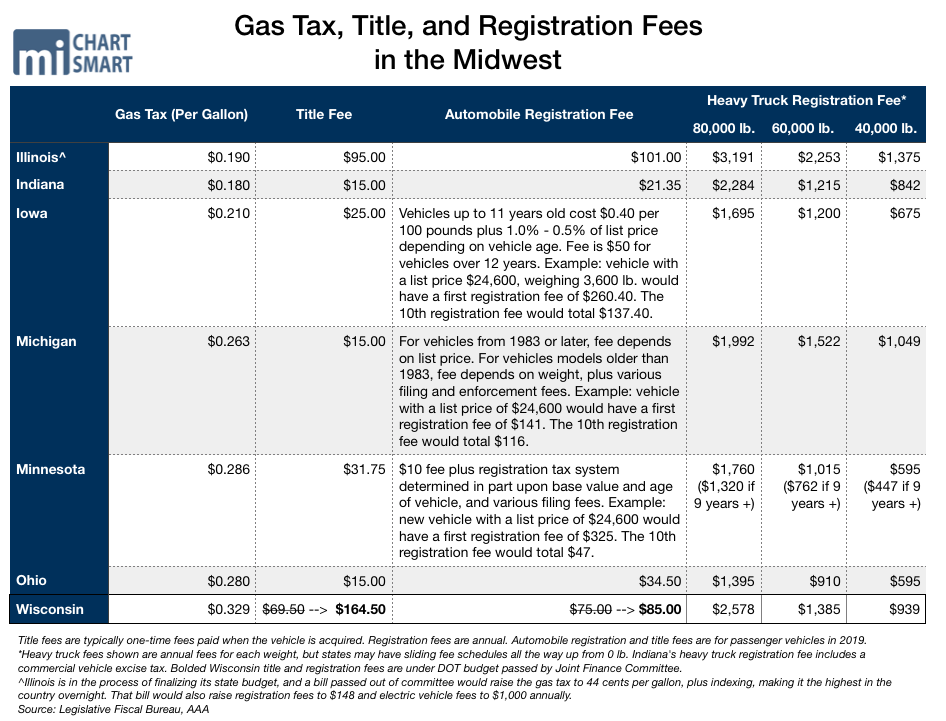

Just because Republican lawmakers in Madison say a gas tax hike is off the table does not mean Wisconsin has made a sudden conversion to fiscally responsible transportation policy. There is still a strong push to increase funding to the Department of Transportation through an increase in drivers’ fees.

As usual, most of the effort seems to be focused on how to collect more money rather than on how to spend it responsibly to maintain the state’s transportation infrastructure. It’s irresponsible to ask Wisconsin taxpayers and drivers to shoulder a heavier burden before the state proves it can be trusted to “just fix it.” The following recommendations would be a good start.

Swap Funding Amounts for GTA With LRIP

GTA does not typically go towards road work. Local governments use that money to fund recurring operating costs like salaries and benefits in their public works departments.

Whenever the state wants to help local governments fix their roads, it typically tries to increase General Transportation Aids (GTA). However, when you talk to local officials, you learn GTA does not typically go towards road work. Local governments use that money to fund recurring operating costs like salaries and benefits in their public works departments. Many local governments will only conduct major road work when they receive Local Road Improvement Program Funds (LRIP) from the state, because that can only be used for actual road work. Unfortunately, the state provides much less support to LRIP than GTA.

The current state budget provides $460 million every year in GTA, and only about $33 million a year in LRIP. Governor Evers wants to increase annual funding for GTA by about $46 million and to LRIP by about $950,000. If the state was serious about fixing local roads, it would consider swapping those increases between GTA and LRIP.

Gas Tax Revenue Must Be Spent on Road Projects

The reason General Transportation Aid (GTA) is so problematic is it can be spent on anything even remotely associated with transportation. That means it covers landscaping, street light electric bills, snow plowing, traffic enforcement, storm sewers, 911 communications centers, bike lanes, etc. Because of this flexibility, GTA tends to become just another form of shared revenue. Its use to fund recurring costs in a local government’s operating budget frees up revenue to increase spending in other, non-transportation related areas.

Such communities will continue to see their roads degrade regardless of how much GTA their local government receives. This situation is even more aggravating because GTA is funded by the gas tax and vehicle fees. (Imagine your registration fees going up, only to end up funding more flower beds along crumbling local roads). Lawmakers could fix this problem by funding GTA through the state’s general fund or requiring that GTAs only be spent on road projects.

Reduce State Oversight of Local Projects

At a Transportation Task Force Meeting this past winter, an unnamed county official bragged about how much he’s able to save on local road projects when he doesn’t tell the DOT about them. It’s not surprising because over-engineering simple projects has been a problem at the DOT for years. Last session Sen. Howard Marklein discovered engineering and oversight of simple projects (like small, standardized bridges) can account for a third of their costs. If local governments have ideas that can save costs without sacrificing safety, the state needs to get out of their way.

Require Better Data Reporting

The state does not track how many miles of road work local governments perform with their $500 million in annual transportation aid.

The state collects a lot of information from local governments when it comes to roads. We know exactly how many miles of road they’re responsible for, how much aid they receive from the state, and how much they’re spending on transportation-related items. One thing we don’t know is how much road work they actually perform each year and what they’re paying for it. This is critical information in determining whether road aid is actually going toward road work, and in helping local governments know if their vendors are charging them a fair price for that work.

The MacIver Institute regularly reached out to local officials individually for that kind of information. Through this admittedly piecemeal approach, we’ve uncovered some fascinating insights. For example, a mile of resurfacing work in Sheboygan County this summer costs about $160,000, while that same work would only cost $90,000 in Grant County. Having that kind of information for every community in Wisconsin would be invaluable to local officials and policy makers hoping to maintain and improve the state’s transportation network.

Find Alternatives to “Cost Plus” Contracts

There are many different kinds of contracts out there, but the only type governments ever seem to write for roadwork is called “Cost Plus Fee.” That means the vendor gets reimbursed for the cost of all their materials, plus they receive a negotiated fee (their profit). Under that model, vendors have no incentive to keep costs down. Some lawmakers have proposed the DOT use a “Cost Plus Award Plus Fee.” The award would be contingent on keeping costs down. That’s a step in the right direction, but there are even better options available that ensure the roadbuilders remain focused on what’s best for taxpayers.

A third type of contract is called “Lump Sum” or “Firm Fixed Price.” The vendor is given a contract for a set amount, and is expected to pay for everything out of that amount and have enough left over for themselves. It’s a great system, because the vendor assumes all the risk instead of the taxpayer.

That’s the type of contract used in the “Design-Build” system. That system involves the state awarding a project to a vendor to not only construct a project, but to work with the state to design it first. The theory is that the company can apply its practical experience to find efficiencies and cost savings that engineers might otherwise miss.

This was recommended by a state audit of the DOT in 2017, but has yet to be adopted. A bill currently circulating would implement a pilot program to give “Design-Build” a try.

Single-Bid Oversight

Since former road lobbyist Craig Thompson took over the DOT, the state has awarded 58 single-bid contracts worth $309 million. Thompson’s department refuses to release the original cost estimates, even after the contracts are awarded.

Since former top road lobbyist Craig Thompson took over the DOT, the state has awarded 58 single-bid contracts worth $309 million. Thompson’s department refuses to release the original cost estimates, even after the contracts are awarded. However, lawmakers did successfully force the DOT to release the estimates for the I-39/90 contract, which showed the single bid was $20 million higher than expected. The state highway program audit in 2017 found that one-bid contracts cost the state an average of $4.5 million a year from 2006 to 2015. A bill is currently circulating that would require the DOT to rebid projects that only received a single bid if it is more than 110 percent higher than the original estimates.

Keep Prevailing Wage Off the Table

There’s no getting around it. Prevailing wage drives up the cost of local road projects. Not surprisingly, local officials get uncomfortable whenever it comes up. When the Transportation Finance Task Force met this past winter, county officials said they want to see more “Fed-Swap” at the local level. That involves consolidating federal funding into as few projects as possible, because federally funded projects are subject to more expensive regulations – most notably prevailing wage.

Bicyclist-funded Bike Infrastructure

During the Transportation Finance Task Force’s meetings this past winter, bike advocacy groups called for requiring bike lanes along all roads, but opposed any kind of fees for bicyclists to help fund it. That shouldn’t be surprising, but it’s also not acceptable. From 1993 through 2014, local taxpayers spent $55 million on bicycle infrastructure, plus another $227 million in federal taxpayer funds – all without any sort of user fee from the bicyclists themselves. This one-sided relationship continues today. To rectify it, the state should consider reducing funding for projects that increase a road’s footprint to accommodate new bike infrastructure, or look for ways to collect user fees from bicyclists.

Chip Sealing Local Roads

More and more local governments across the state are discovering the merits of using chip sealing in their road maintenance strategies. Resurfacing a road costs about $90,000 a mile, while chip sealing costs about $9,000. The technique is not a permanent fix, but it does an excellent job preserving pavement until it’s due for resurfacing. Marquette County relied heavily on this technique to achieve the best local roads in the state in 2017. The state should find ways to encourage its use when disbursing local road aids.