The MacIver Institute examines the data and studies on the effectiveness of a mask stopping the spread of COVID-19

Review finds clear flaws and limitations in studies that are propped up by mainstream media to support mask mandates

Mixed conclusions on asymptomatic spread

Aug. 14, 2020

The push to require the wearing of masks to fight the spread of COVID-19 has taken on a greater urgency lately, with many state and local governments passing emergency orders to mandate the public wear a mask while in an enclosed space or Orwellianly defined indoor-outdoors in some municipalities.

Proponents of mask mandates, including major media outlets like PolitiFact, say the science is settled. They point to supposedly ironclad research that shows masks are incredibly effective in stopping the spread of germs from person to person and are necessary to win the battle against COVID-19. Many in the mainstream media have refused to ask basic questions about and challenge whether the research actually proves masks are an effective tool in the fight against COVID-19.

Where others say the science is settled, our analysis shows that is not the case. We break down the most widely referenced studies on masking policies so you can see for yourself what the data really says. We should also point out that it is unscientific to claim that the science is settled. Science is always a work-in-progress and we should never make the false claim that a scientific theory is settled as fact.

In reality, coronavirus studies have yet to mature to a point of giving prevailing evidence in favor of universal masking policies.

Studies Often Referenced On Masks And Mask Mandates

1. University of California – San Francisco: A Literature Review

A study out of the University of California-San Francisco(UCSF) made the case that wearing a mask will reduce severe cases of the coronavirus because masks will only let a little bit of the virus into the body and only cause a mild infection. They support their hypothesis by postulating that masks do not prevent all virus particles from entering or escaping the mask.

This study did not include any original research. It was a literature review that examined various anecdotes, including virus mitigation practices used by people on cruise ships, in a pediatric dialysis wing in an Indiana hospital, at food processing plants, and among Swiss soldiers. We should point out that anecdotal investigations are not evidence bearing. They indicate a possible direction for drawing conclusions, but they are by no means factual.

The Swiss example held the most promise. One group of soldiers instituted virus mitigation policies while another group acted as normal. The group that employed these mitigation policies saw no infections, while the group without the policies saw a 30% COVID-19 infection rate. The UCSF study used these anecdotes to conclude that universal masking absolutely causes future infections to be less severe.

The UCSF study ignored the impact of other mitigation practices that were implemented concurrently with facemasks, such as hand washing, social distancing, properly covering coughs and sneezes, and others. We are curious why researchers would disregard the impact of those other measures and not factor in the possibility that the other measures could have had an impact on the results. It is a stretch for the authors to conclude that mask wearing was the single most important factor that mitigated against more severe cases of COVID-19.

2. Health Affairs: Public Policy Assumptions

Another study from Health Affairs, referenced by the Journal Sentinel, suggests that mask mandates alone curbed the spread of the coronavirus in 15 states and Washington DC. The authors say that they measured how fast the virus spread in each state and how the spread declined up to 21 days after each state instituted their own mask mandates.

The authors report that the daily rate of the spread declined by up to 2% 21+ days after the mandates were in effect. They don’t say what the rate of spread was before the mandates were passed.

The study also does not consider other variables at play, like continuously changing social patterns during the study period. All that is clear from this study is that “the suggested benefits from mandating face mask use are not substitutes for other social distancing measures; the effects are conditional on the other enacted social distancing measures and how communities are complying with them.”

Even that last statement is problematic. In a dynamic social system like one would find in any city or community, it is impossible to state that a single factor is the cause for a given outcome. In order to suggest that, you would have to use a control group comparison and none of that was done in the study.

3. CDC: According To My Hairdresser…

A study by the CDC points to a case in a Missouri hair salon as more proof for the effectiveness of mask mandates.

Back in May, two hairdressers had COVID-19 and kept seeing customers for over a week after their symptoms began. They wore masks while they worked, the majority of their clients wore masks during their haircuts, and none of the clients became sick after exposure.

There were at least 4 other factors that could have mitigated the spread of the disease. For example: customer’s hand washing and general hygiene habits and the stylists working behind the client (not in front of them) could have mitigated spread.

The study says that “no studies have examined SARS-CoV-2 transmission directly.” But, “in countries that did not recommend face masks and respirators, the per-capita coronavirus-related mortality increased each week by 54.3% after the index case, compared with 8.0% in those countries with masking policies.” Here is another place where the study does not acknowledge the effect of additional protective measures, like distancing, on the spread of the virus.

4. CDC: Singling Out Masks At A Massachusetts’ Hospital

At the Mass General Brigham hospital system in Massachusetts, another study was conducted before and after a system-wide mask policy was issued. Before requiring masks, the rate of infection among the hospital system’s employees reached 21%. Two weeks later, the rate of positive tests among employees dropped from 13.65% to 11.46%.

It is curious that the rate of infection dropped from 21% to 13.65% before the effect of a mask mandate could be seen. Despite the preemptive decline, the study authors concluded that “these results support universal masking as part of a multipronged infection reduction strategy in health care settings.” The study only recommends this for healthcare settings, and their investigation does not take the effects of the other parts of their mitigation strategy, like testing and quarantine, into account.

5. New England Journal of Medicine: False Comparisons

PolitiFact referenced a study from the New England Journal of Medicine that did an experiment on droplets when speaking. Using a green laser to measure droplets spat out by a speaker, the study showed a lot of droplets released when someone speaks, especially at louder volumes and when they make certain sounds with their mouths. The study showed almost no visible droplets when the speaking person covered their face with a damp washcloth. The problem with this study is obvious: a damp washcloth is not the same as the kind of face masks people are wearing now. There’s no comparison. Furthermore, unless the viral load of the droplets is measured, there is no way to conclude that droplets from the mouth were causing the spread of a virus.

6. Gov. Evers: N95 Respirators And Cloth Masks Are The Same Thing, Right?

Gov. Evers directly referenced statistics from two studies in his emergency mask mandate order. One part of the order reads that, “Published scientific research has shown that the probability of transmission during exposure between a person infected with COVID-19 to an uninfected person is 17.4 percent if face coverings are not worn, and 3.1 percent if face coverings are worn.”

This statistic comes from a review published in The Lancet journal in May 2020. The review analyzed 164 studies on the spread of respiratory viruses, including COVID-19, and how the spread is impacted by masks, eye coverings, and social distancing. It concluded that at least 3 feet of social distancing, and up to 6.5 feet, is the most important factor to stopping the spread, not masks. Their data suggests that masks do help mitigate spread. However, the mitigation was more closely associated with N95 respirators than with typical cloth masks. “Nevertheless, given the limitations of the data, we did not rate the certainty of effect modification as high.” This is supposition, not confirmation.

7. WHO: There Is No Direct Evidence

Finally, the World Health Organization (WHO) reviewed multiple studies on the effectiveness of masking in their June 5, 2020 guidance document. Their review noted that “There are currently no studies that have evaluated the effectiveness and potential adverse effects of universal or targeted continuous mask use by health workers in preventing transmission of SARS-CoV-2.” The report also mentioned some previous studies on how masks may have slowed the spread of the flu in college settings, but those studies “showed no impact on risk of laboratory-confirmed influenza.”

The WHO review says “At present, there is no direct evidence (from studies on COVID- 19 and in healthy people in the community) on the effectiveness of universal masking of healthy people in the community to prevent infection with respiratory viruses, including COVID-19.”

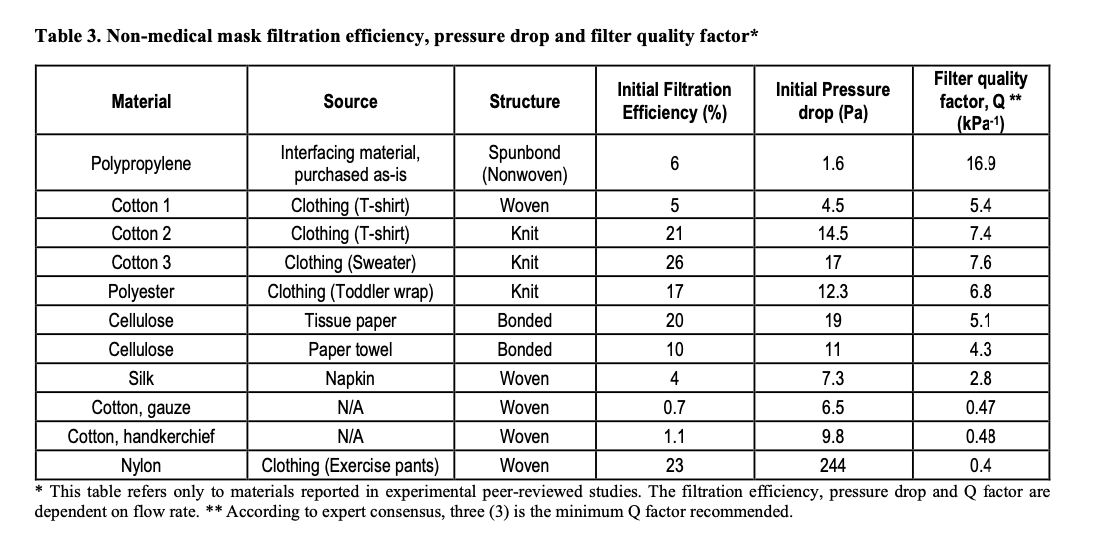

The WHO does, however, have information in their document on how well non-medical masks work to filter out virus particles. The WHO writes that most homemade cloth face masks, depending on the material, can filter out between 0.7% and 60% of particles. A single layer of a cotton handkerchief filters out only 1.1 percent of particles, according to the document. If the handkerchief is layered 4 times, it can filter out only 13% of particles. A single layer of a knit cotton sweater can filter out 26% of particles.

Homemade masks filter out more particles the more layers of fabric are used in the mask. However, the guidance document says with each layer it gets harder to breathe with a homemade mask.

Because non-medical masks filter out less particles and are less breathable than a medical-grade mask, the WHO says only people who are infected should be recommended to wear a non-medical mask to keep the virus to themselves. Homemade masks could be used by the general public, the WHO says, in crowded public places, but “should always be accompanied by frequent hand hygiene and physical distancing.”

The authors give a table for when mandatory masking policies should be issued. They say the choice to mask an entire population is dependent on “the local context, culture, availability of masks, resources required, and preferences of the population,” but not dependent on the effectiveness of masks.

Studies On Asymptomatic Spread – Do Masks Stop The Spread Of The Virus By Asymptomatic People?

Where the science on masking healthy people is uncertain, scientists and public officials say mask mandates must be issued, regardless of the fact that there is no scientific study that definitively proves the effectiveness, in order to stop the spread of the coronavirus by asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic people.

Asymptomatic people are those who are infected with the virus without ever showing symptoms of the virus. Pre-symptomatic people are infected with the virus and have not shown symptoms yet, but do show symptoms of the virus later.

Some scientists are urging mask mandates, while at the same time admitting that the jury is out on how many people are asymptomatic, or infected without symptoms, and how much COVID-19 is spread by asymptomatic people. But that begs the question: How can we say that masks will stop the spread by asymptomatic people if we do not know how many people are asymptomatic in the first place? It also does not answer the question of: can masks do harm to the people who are wearing them? The statements supporting mask mandates all assume no negative side-effects from mask wearing. The logic here is inescapable: if wearing a mask can mitigate harm, it can also cause harm. Can we quantize the level of harm that wearing masks will cause? Where are the studies researching this?

1. CDC: Best Guesstimate

A popularly referenced CDC piece analyzes multiple studies on asymptomatic spread and concludes that 40% of COVID-19 infections are asymptomatic. The CDC calls this their “best estimate” because there are more ways to estimate asymptomatic spread than that.

According to the review, anywhere from 10% to 70% of COVID-19 cases could be asymptomatic. The CDC’s best guess is that asymptomatic COVID-19 cases spread the virus at 75% the rate that symptomatic infected people do. Estimates on rate of asymptomatic spread range from 25% to 100% the same rate as symptomatic infections. The authors also estimate that, among all infected people, 50% were infected by somebody who did not have symptoms at the time. That estimate ranges from 35% to 70%. If the brakes on your car worked 35 to 70% of the time, would you trust their reliability?

Ultimately, the CDC analysis concludes that:

- “The percent of cases that are asymptomatic, i.e. never experience symptoms, remains uncertain.”

- “The relative infectiousness of asymptomatic cases to symptomatic cases remains highly uncertain as asymptomatic cases are difficult to identify and transmission is difficult to observe and quantify. The estimates for relative infectiousness are assumptions”

- “The current best estimate is an assumption.”

2. WHO: Best Guesstimate

We referenced a study review earlier by the WHO from June 5, 2020. That review also gave a wide range of estimates for how common asymptomatic infection and spread is. The authors found one review where asymptomatic cases accounted for 6-41% of all COVID-19 cases analyzed. The WHO review mentions another study that found, out of 63 people with asymptomatic cases of COVID-19, 14% of them passed the virus to someone else.

WHO’s analysis says that studies and data are very limited on COVID-19, and the studies that do exist suffer from flaws like limited sample sizes of patients and poor reporting of symptoms monitored during the studies.

The authors conclude that, out of the limited studies and evidence worldwide, the data “suggests that asymptomatically-infected individuals are much less likely to transmit the virus than those who develop symptoms.”

That throws a wrench in the argument that asymptomatic spread is so dangerous, everybody in a population needs to wear a mask to stop the spread.

3. Heritage Foundation: Mixed Case Study Messages

Peter Brookes of the Heritage Foundation comes to a similar conclusion on the effectiveness of masks for asymptomatic spread. He mentions three case studies, one of them taking place on the Diamond Princess cruise ship. Among cruise ship passengers who tested positive for the coronavirus, 18% had no symptoms. Brookes mentions another case among Japanese evacuees from Wuhan, China at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak. 31% of those evacuees who tested positive for the virus had no symptoms of infection. The author then talks about a third instance in Iceland, where the country had tested 5% of their population at the time. Iceland then had reported 50% of their positive diagnoses showed no COVID-19 symptoms.

Things To Think About When Determining If A Study Is Accurate And Definitive

Studies like the ones above have been highlighted as sound guidance for penning public policy on community masking. However, each of these publications suffer from flaws, assumptions, and limitations. Below are a few of the most common issues we observed in our review. Issues like the ones below should be considered to decide for yourself if a masking or COVID-19 study is accurate and complete:

- COVID-19 is a new virus and, unsurprisingly, there are few studies that have been completed on the virus at this time.

- Many new studies make hypotheses about how to treat COVID-19 based on existing data on SARS, MERS, and the flu. Applying data on SARS, MERS, and the flu to COVID-19 may not be effective or relevant.

- None of the studies here investigate how age may determine the effectiveness of masks or the prevalence of asymptomatic infection. MacIver has found that the age question is crucial to understanding the spread of the virus. It is, therefore, irresponsible to exclude questions about age from these studies. It is also clear from mask mandates around the US that the age at which masks are required range from 3 to 11. It is clear from this that there is no evidence to support which age would be the right age.

- Many studies conclude that masks are the X-factor for reducing virus transmission. Authors reach this conclusion, however, by ignoring the effects of other mitigation strategies – hand washing, sanitizing surfaces, physical distancing, properly coughing and sneezing into your elbow, etc. These measures reduce COVID-19 transmission and may very well be more important and effective in the stopping of the spread of the virus. They also completely ignore the fact that regardless of mask wearing, a certain percentage of people within a population will still get the virus. There have been no credible studies nor claims that pretend a given number of people will contract COVID-19.

- Many studies are very limited by the number of people in their study group. If a study looks at COVID-19 infections in 100 people, it is impossibly hard to take conclusions from the study and apply them to a population of millions of people. This is the antithesis of proper scientific research.

- The evidence that studies presented does not support the authors’ premises that mask mandates will and must protect an entire population. Their studies also don’t prove definitively how often COVID-19 is spread asymptomatically, which defeats the argument that masks should be required to stop the asymptomatic spread of COVID-19.

- Many studies assume that asymptomatic cases are just as dangerous as symptomatic cases, so masks need to be used to prevent both. The limited data does not support this idea.

They Said At First No Need To Wear A Mask, Now Everyone Must

In addition to the non-conclusive studies on the effectiveness of masks and asymptomatic spread, early health experts actually discouraged the public from wearing masks.

The US Surgeon General, the CDC, and Dr. Anthony Faucci advised from the beginning that the sick and the medical community will benefit from wearing masks, not the general public.

At the end of February, Surgeon General Jerome Adams was tweeting that masks “are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus, but if healthcare providers can’t get them to care for sick patients, it puts them and our communities at risk!”

Seriously people- STOP BUYING MASKS!

They are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus, but if healthcare providers can’t get them to care for sick patients, it puts them and our communities at risk!

https://t.co/UxZRwxxKL9— U.S. Surgeon General (@Surgeon_General) February 29, 2020

In a 60 Minutes interview in March, Dr. Faucci said wearing a face mask should be reserved for “healthcare providers needing them, and people who are ill.”

“There’s no reason to be walking around with a mask. When you’re in the middle of an outbreak, wearing a mask might make people feel a little bit better, and it might even block a droplet, but it’s not providing the perfect protection that people think that it is,” Faucci said.

Their guidance rapidly changed in early April to recommending masks for the general public.

“The CDC, the World Health Organization, my office, and most public health and health organizations and professionals originally recommended against the general public wearing masks, because based on the best evidence available at the time, it was not deemed that that would have a significant impact on whether or not a healthy person wearing a mask would contract COVID-19,” said Surgeon General Adams at a White House press conference on April 3.

Adams explained that new evidence about asymptomatic spread of the virus had led the COVID-19 task force and the CDC to recommend “wearing cloth face coverings in public settings where other social distancing measures are difficult to maintain. These include places like grocery stores and pharmacies. We especially recommend this in areas of significant community-based transmission. It is critical.”

Dr. Faucci talked about his changed position with Bloomberg News’ David Westin on August 5. Along with hand washing, social distancing, and staying away from crowded places like bars, Faucci says it’s fundamentally important to control the spread of COVID-19 by “wearing masks universally, indoor and outdoor.”

“For me as a public health official, obviously I would like the consideration that everybody wears a mask,” he said to David Westin. But he also acknowledged the pushback by people at the state level against mask mandates. So instead, Faucci says, “If we uniformly and consistently give the message that it is extremely important to wear a mask, that could be as good as a mandate.”

The CDC has since changed their message as well. Their website now says that “Everyone should wear a cloth face cover in public settings” because “You could spread COVID-19 to others even if you don’t feel sick.”

National guidance continues to recommend face masks for the sick.

“We have always recommended that symptomatic people wear a mask, because if you’re coughing, if you have a fever, if you’re symptomatic, you could transmit disease to other people,” the Surgeon General said in April.

All sources stressed that masks are not meant to substitute physical distancing and other hygienic practices.

Media Narrative Does Not Match The Data

These studies show that masks, social distancing, and eye protection do have some effect on the spread of COVID-19. N95 masks and social distancing appear to be the biggest deterrents to virus transmission.

The studies here also make clear that the science is not clear at all, but you would not know that from reading the media description of the studies. The research hasn’t figured out yet how much virus transmission is stopped by wearing a mask, and still hasn’t determined how many COVID-19 infections come from the asymptomatic cases that mask proponents say they’re targeting.

The current body of research is flawed, vague, and incomplete at best.

Still, scientists, public officials, and pundits recommend or strongly urge mask mandates on a massive scale.

A July 14 editorial by three CDC physicians in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) sums up this logic nicely: “In the absence of such data, it has been persuasively argued the precautionary principle be applied to promote community masking because there is little to lose and potentially much to be gained.”

What mainstream media and well-known medical officials seem to miss is that a “precautionary principle” is not the same as science. In fact, the science we see here gives us no concrete answers yet. Lacking evidence cannot be an excuse for leadership to lie and compel private citizens to all wear masks.

The media narrative continues on saying masks do work, mandating masks will work, and mask orders are the only way to stop the further spread of the coronavirus. Based on the studies reviewed here, that conclusion doesn’t follow the science.

Not Seeing Your Favorite Mask Study Here?

If there’s another study being cited in the face mask public policy debate you’d like us to investigate, email us at info@maciverinstitute.com