Political Agenda Includes Living Wage, Repeal of Voter ID, Rectifying Historic Injustice

Multi-Million-Dollar Fund Recipient UW Population Health Institute’s In Solidarity Podcast Now Pushes Reparations

As we’ve reported often including here, here, and here, nearly 2 decades ago, a $600 million endowment was created by the conversion of Blue Cross and Blue Shield United of Wisconsin from a non-profit to a for-profit insurance company. The endowment was shared equally by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health (UWSMPH) and the Medical College of Wisconsin. The schools are required to allocate 65% of the funds for medical education and research, and 35% for public health initiatives.

Over the years, the UW program has come under fire for skimming hefty administrative fees out of the endowment, something they still do, although the agreement is clear that the funds may only be used for public health. More recently, the UW lost a public records lawsuit filed at their refusal to release records and violations of open meetings laws related to conflicts of interest in the awarding of Partnership grant funds.

The UWSMPH allocation of funds has also been frequently criticized for deviation from the program goals and intent, which were clearly spelled out in the endowment to be specifically and only related to public health.

Early grants predominantly held to public health goals; infant mortality, rural birth outcomes, oral health, fall prevention, STD prevention, rural physician shortages, and diabetes. While comparatively little was directed to rural health, most going to urban and metro areas, the main focus was public health.

But then the UW began to shift the focus from the public health initiatives the fund was intended to support.

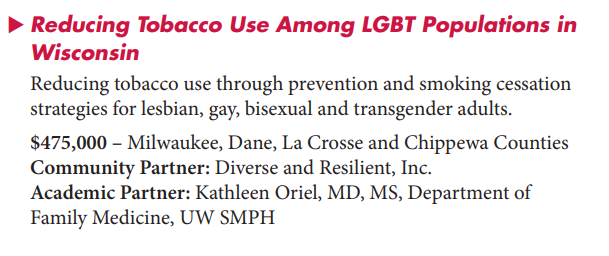

Just a few years in, among the grants were a half-million-dollar gardening project, a half-million-dollar “ecocultural interview project,” and a third half-million-dollar project to reduce tobacco use, but only among the under 4% of Wisconsin’s population that identifies as LGBT.

Just a few years in, among the grants were a half-million-dollar gardening project, a half-million-dollar “ecocultural interview project,” and a third half-million-dollar project to reduce tobacco use, but only among the under 4% of Wisconsin’s population that identifies as LGBT.

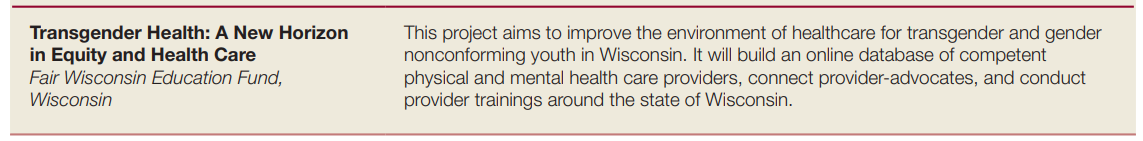

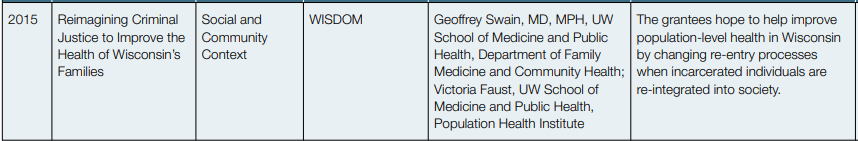

A few years later there was a million-dollar grant for “Reimagining Criminal Justice,” and Fair Wisconsin, a group with an affiliated Political Action Committee which supports political campaigns of solely Democratic candidates, received funding for a transgender equity project.

Another group, MICAH, heavily involved in the movement to release half the prison population received two pots of money totaling over $300,000, one to decrease racial disparities in-school suspension and another to “address social justice issues.” And a Madison group working to “preserve the vitality of neighborhoods” in Madison through racial equity got another $300,000.

Recently, the UWSMPH funded a project to provide “legal interventions” to low-income people and gave the McFarland School district $1 million for their anti-racism plan.

These grants have moved far afield from public health issues, and into deeply political territory. As one marker of how their attention has shifted away from the public health issues facing the state, their 5-year plan for 2019-2024 mentions equity 33 times, rural 10 times, and elderly/senior/aging not one single time; but in their 2014-2019 5-year plan, rural was mentioned 9 times, equity 3, and elderly/senior/aging once. Our state is rural and aging and those populations are the sickest and costliest – and have huge health disparities – but if the focus is racial equity, they don’t fit the bill.

The UWSMPH Partnership website features a “hub” for equity, and a “hub” for funding – but no “hub” for health. They don’t even bother with window-dressing anymore.

Though specifically prohibited from using these funds to supplant other spending, and despite the billions of federal COVID dollars pouring into all levels of government, public health agencies, and health care organizations, UWSMPH funded $6 million in COVID projects.

These are just the projects they choose to publicize. There have been 550 grants awarded by UWSMPH in the past 18 years, and it’s a fair bet that there are more, and more striking, violations of the intent of the funds.

The Population Health Institute of the UWSMPH has been a consistent recipient of Wisconsin Partnership funds, and they recently sponsored a podcast advocating for reparations for the descendants of slaves. Population Health’s slate of current projects, along with their most recent Health Report Card (recently renamed the Health Equity Report Card) funded by Wisconsin Partnership funds, advocates for policies including reparations to descendants of slaves, and reparations for past housing policies for people of color, universal basic income, racial wealth building, elimination of voter ID, expanded mail voting, and living wage laws.

Anyone would be forgiven for thinking these initiatives sound more like a Democratic campaign platform than a plan to improve the health of Wisconsinites.

While the SMPH has shifted focus to heavily politicized social issues and away from public health, Wisconsin’s health rankings have fallen from 7th healthiest in 1990 to 23rd in 2018. According to the Wisconsin Medical Journal, between 1990 and 2018, Wisconsin’s rank dropped precipitously in Infectious diseases (-37 spots), infant mortality (-16), and violent crime (-14, and this predates the recent spike in violent crime). Yet, projects UWSMPH funds focus on keeping criminals on the streets, not reducing violent crime.

And while our health ranking is falling, our cost of healthcare is among the highest in the nation, making it even more vital that investments to improve public health are made wisely, and not politically.

But increasingly academia has rejected the basics of good public health – efforts to improve health that impact the population broadly – and instead focuses on “equity,” “historic injustices,” “oppression,”, “structural racism,” “solidarity,” and “power” along with vehicle scrap programs, walking school buses, CAFO regulations, public transit, tillage practices and traffic calming. In these circles, public health crises now include racism, violence, climate change and election integrity. Diabetes, not so much, unless caused by oppression.

Meanwhile back in the real world of health, the third leading cause of death in the U.S. is now medical error.

The sicker, poorer, costlier, more rural elderly – and predominantly white – population is growing, their healthcare needs are already beginning to outpace the capacity of our health care labor force. And it’s not just the elderly at risk; over a quarter of our counties do not have an OB-GYN, compounding an already large disparity between rural and urban birth outcomes for mothers and babies.

Shortages of healthcare workers will continue to grow, and rural areas will continue to bear the brunt of those shortages. In under a decade, there will be 25% fewer physicians practicing due to retirement. Graduating medical school students are completely disinterested in serving rural populations. Only 1% want to work in communities under 10,000, and only 2% have an interest in those under 25,000. That means only 2% of graduating doctors are willing to serve areas where 60% of our state’s population lives, math that bodes ill for healthcare access, quality, and outcomes.

Wisconsin’s public university and technical colleges do not even bother to track the number of qualified applicants they turn away from nursing programs, even though the shortage of nurse practitioners in the nation is approaching 30,000.

The Wisconsin Partnership funds were meant to serve the public health of the state, but the UWSMPH program has hijacked much of the public health mission to advance political narratives. Take the newly-released, Wisconsin Partnership-funded Wisconsin Population Health Equity Report Card take on health in race: systemic racism alone is responsible for racial health disparities.

It’s worth considering that better health isn’t best sought by loosening voting integrity laws, or paying reparations, or by providing legal services, or emptying prisons, or tilling fields differently. It’s possible that better public health could be achieved by looking at the actual healthcare needs of the people of the state.

The UWSMPH and the members of their oversight committee, who are recommended by the Board of Regents and Office of Commissioner of Insurance, should refocus their giving to address the public health needs of the state, and stop working to advance the social agenda of a political party.