In the coming months, we’ll see 3 issues at the intersection of welfare and work take center stage in Wisconsin.

- A statewide ballot question on whether voters want to see able-bodied, childless adults on welfare be required to work or seek work.

- The “unwinding” of the 3-year long pandemic policy of allowing people not legally eligible for Medicaid to continue receive benefits.

- The end of pandemic add-on FoodShare benefits, and the ongoing waiver of program work requirements.

On April 4, Wisconsinites will weigh in on 2 ballot measures, along with their choice for Supreme Court. The first statewide ballot question could give final approval to a constitutional amendment allowing threat to the community to be considered setting bail for violent offenders. We strongly support this amendment as a first step toward protecting communities, while holding criminals accountable.

The second is an advisory referendum on whether able-bodied childless adults on welfare should be required to work or seek work. We at MacIver believe this is also a good first step toward moving people back into the workforce.

All three are weighty decisions; the question of able-bodied welfare recipients being asked to work comes at a time when welfare rolls are historically high, the labor force participation rate has dropped to historic lows, and unemployment is near-historic lows. Employers are having trouble finding workers; the Job Center of Wisconsin lists 105,000 jobs, and only 35,000 resumes are posted.

Welfare and Work By the Numbers

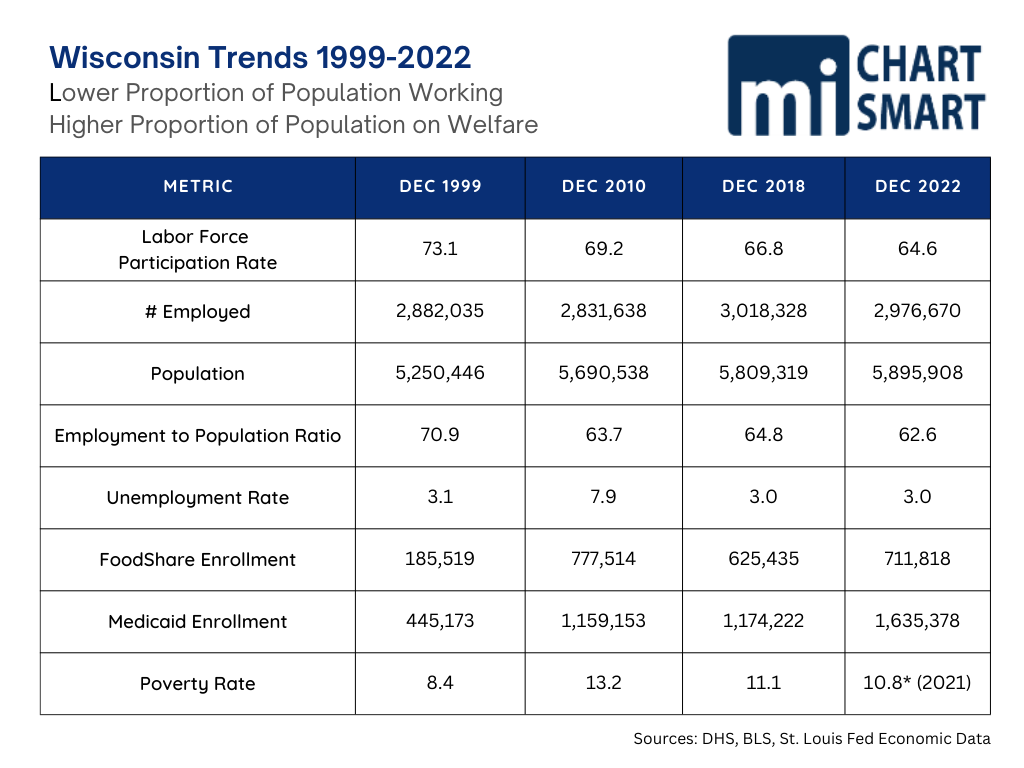

The chart below shows a number of metrics related to growing welfare dependence and shrinking participation in work between 1999 and 2022. The first comparison to note is that while the state population has grown nearly 650,000, the number of people employed has increased less than 100,000.

The labor force participation rate, which measures the percentage of population working or looking for work, has seen a sustained drop. A 2022 working paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago concluded that the drop in the rate is due to an “overall lower willingness to work” and the drop in desired hours of work is pervasive across demographic groups with a slightly larger decline among those with less than a college degree and is concentrated among people who prefer to work infrequently, and when they do work, prefer only part time hours.

The employment to population ratio measures the proportion of the working-age population that is employed, including those who are not looking for work. This metric has also seen a sustained drop, and coupled with our low unemployment rate is low, shows a growing proportion of the workforce is not working.

Finally, the welfare rolls have increased precipitously and the slight increase in the poverty rate is not enough to have driven such increases. The growing unwillingness to work is obviously a growing factor driving welfare enrollment, and potentially contributing to the poverty level.

Should Able-Bodied Adults Work?

The question of whether the able-bodied childless adults on welfare should work also comes at a time when 3-year-old pandemic welfare eligibility and benefit waivers are ending and reverting to normal levels. Mainstream media headlines are screaming that giving standard welfare benefits to only those legally eligible for welfare is cruel.

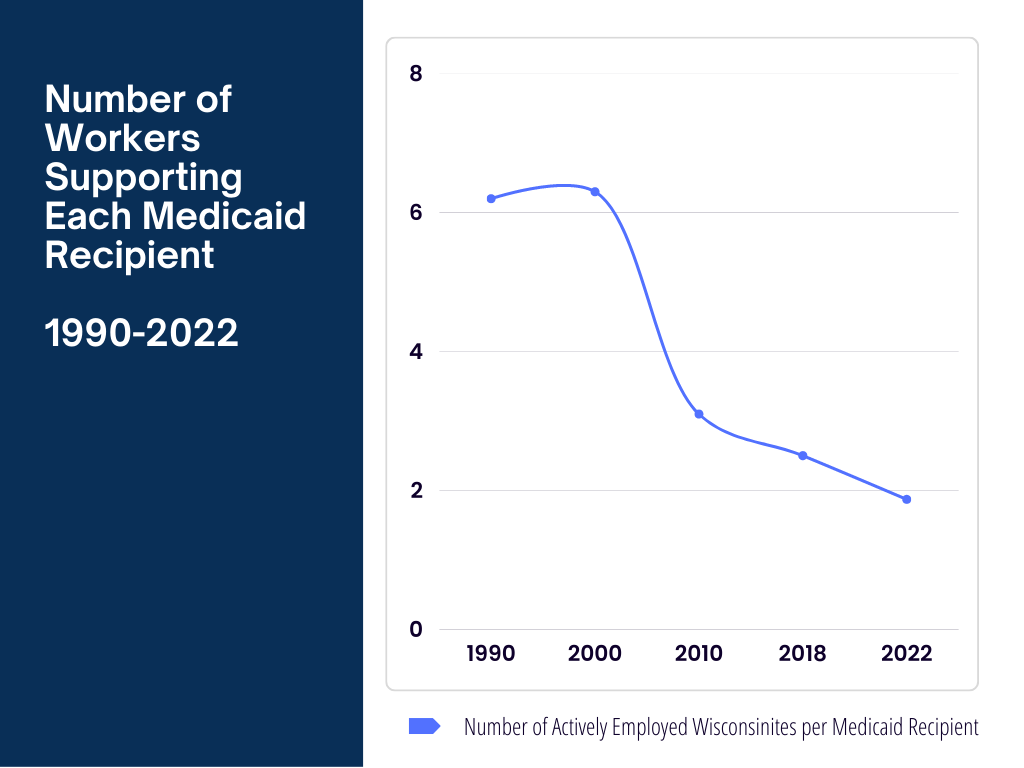

But 28% of the state’s population is on Medicaid, and there are fewer than 2 employed Wisconsinites working to finance benefits for every Medicaid recipient. In 2000, there were more than 6 workers financing each MA beneficiary. Meanwhile Wisconsin’s successful FoodShare Employment and Training (FSET) program that helped train and connect able-bodied FoodShare recipients to work has also been sidelined throughout the pandemic.

The work for welfare question brooks immediate, forceful opposition from the left, whose resistance has grown over the years along with the number of government dependents. Most of us still work to provide for our own food and shelter, and other needs and wants – and we expect others to as well.

Wisconsin’s own Red Forman may have said it best.

Our formerly strong Midwestern work ethic is fading, and the growing group that finds work a boring, traumatic hassle that gets in the way of empowerment and self-actualization thinks that those of us who have accepted the oppression of a job may as well just provide for their wants and needs.

Since we’re already up.

What’s Past is Prologue:

A Brief, Recent History of Welfare in Wisconsin

Generosity Exploited: Wisconsin as a Welfare Magnet

The push and pull on the issue of welfare is not new to Wisconsin. Surveys show a strong majority still believe that able-bodied adults should work, particularly in a strong economy, and that welfare should not be a career choice. At the same time, Wisconsinites have a history of being generous to those in need and have traditionally provided benefits higher than those in many other states.

Our welfare benefits had become so generous in the 1970s and 80s that in 1985, a UW researcher, commissioned by the state Department of Health and Social Services to study in-migration of welfare recipients found that for every one welfare family moving from Wisconsin to Illinois, 3 families moved the opposite direction.

That same year, Democratic Governor Tony Earl created an expenditure commission which also looked at Wisconsin’s status as a ‘welfare magnet’ under the direction of the University of Wisconsin Applied Population Lab (UW’s Institute on Poverty Research refused to participate on the grounds that the issue was politically charged – something they have since embraced quite fully.) This work showed between 7 and 20% of people who migrated to the Wisconsin were influenced to do so because of our higher welfare benefits.

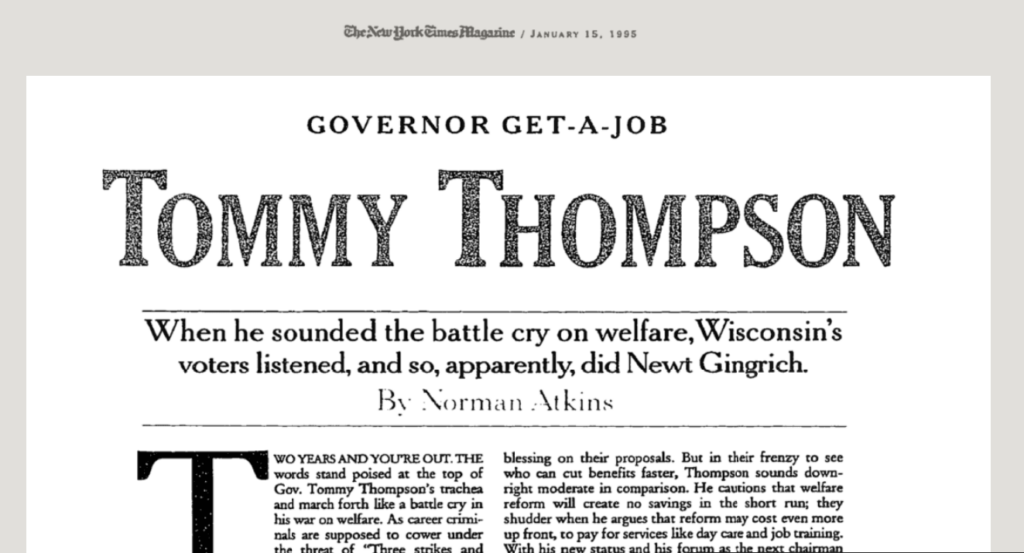

Earl’s successor Governor Tommy Thompson took office in 1987, just before another report on welfare in-migration showed between 1985-88 nearly 30% of new welfare applicants had never lived in Wisconsin previously; in Milwaukee the figure was over 46%.

Governor Get-a-Job

Thompson took Wisconsin’s welfare problem head on, and while some on the left groused (one UW professor said that people moving here for higher benefits proved they had the kind of “drive” that meant they wouldn’t stay on the welfare rolls long) Joe Strohl, the Democratic Senate Majority Leader at the time said,

“It is time that we Democrats admit that people really are moving here because of our higher benefits, and begin to address it.”

Under Governor ‘Get-a-Job’ Thompson’s leadership Wisconsin became the national model for welfare reform, and he did so with large democratic majorities in both houses of the legislature. We tied work, education, and intact families to time-limited welfare benefits, and our programs like Workfare, Learnfare and Bridefare became household names.

Wisconsin went from 287,488 AFDC recipients in 1987 to 94,802 in 1996. Thompson had proposed Medicaid reforms as well, including decoupling it as an entitlement for AFDC groups, but his waiver proposals were denied by the Clinton Administration.

Public support for these ‘handup-not-handout’ reforms was so strong that in 1996 President Bill Clinton, after vetoing two Republican-authored welfare reform bills, finally signed one into law giving states more autonomy and reducing the role of the federal government. It also broke the link between cash welfare payments through AFDC and Medicaid, something his administration had refused to allow Republican Thompson to do in Wisconsin.

BadgerCare Begins

In 1997, Medicaid enrollments had decreased roughly 22% and state officials were concerned that working families transitioning off welfare were falling through the cracks created by the federal decoupling of MA and AFDC. Thompson directed his administration to work with a bipartisan coalition to develop and seek a federal waiver for what would become BadgerCare, to help provide coverage for those low-income working families.

In 1998 the Urban Institute described Wisconsin’s Medicaid program as having generous eligibility standards, a rich benefit package, and spending increases below the national average; not a budget buster but a program that needed to be managed. By 1999 Thompson finally won approval from the Clinton Administration, again with broad bipartisan support, for the BadgerCare waiver.

The work component was central to the mission, discussion, agreement and advertising on BadgerCare. The program aimed to help ease the transition from welfare to work for low-income parents with children as welfare reform efforts continued.

BadgerCare blew through all enrollment and cost estimates almost immediately. Enrollments of parents was more than 80% above projections and it was far more expensive to cover them than expected. Just 5 months into the program, the state had to start working on an agreement to increase capitation rates for BadgerCare recipients. This began the steady growth of the program both in enrollment and cost.

Doyle Adds Able-Bodied Childless Adults

Thompson’s successor, Governor Jim Doyle won approval from the Obama Administration in 2009 to expand BadgerCare to cover childless adults up to 200% of FPL. As with the original BadgerCare expansion, demand for the program almost immediately exceeded projections, and tens of thousands were placed on a wait list.

In 2010, as a lame duck ahead of Scott Walker’s election, Doyle signed legislation sent by the Democrat legislature attempting to end the wait list by requiring a $130 monthly premium from the able-bodied childless adults for a stripped-down benefit plan. Sold as a way to “self-fund” the recipients with no state or federal funds, the premiums fell far short, but this was left for the incoming governor to sort out when Doyle lost in November.

Walker Reforms BadgerCare, Leverages ObamaCare Exchanges

Doyle’s successor Governor Scott Walker received approval for a waiver to reform BadgerCare to cover able-bodied childless adults up to 100% FPL under BadgerCare and to charge premiums for able-bodied parents with incomes above 133% FPL.

When the Obama Administration signed the Affordable Care Act, Wisconsin was already one of the most generous Medicaid programs in the nation. Walker had the benefit of having watched the explosion of Wisconsin’s MA rolls every time a new plan to cover a ‘few more people with cost neutrality’ added thousands of people and cost millions of dollars.

Walker chose to limit Wisconsin’s BadgerCare coverage to those in poverty (children are covered in families with income up to 305% of FPL) allowing those above FPL to participate in the heavily subsidized exchange plans, created by the Obama Administration to guarantee affordable coverage to everyone between 100% -400% FPL through subsidies and cost-sharing. Currently, anyone between 100-150% FPL have a $0 required contribution for a benchmark plan and receive additional cost-sharing reductions as well as out-of-pocket spending limits.

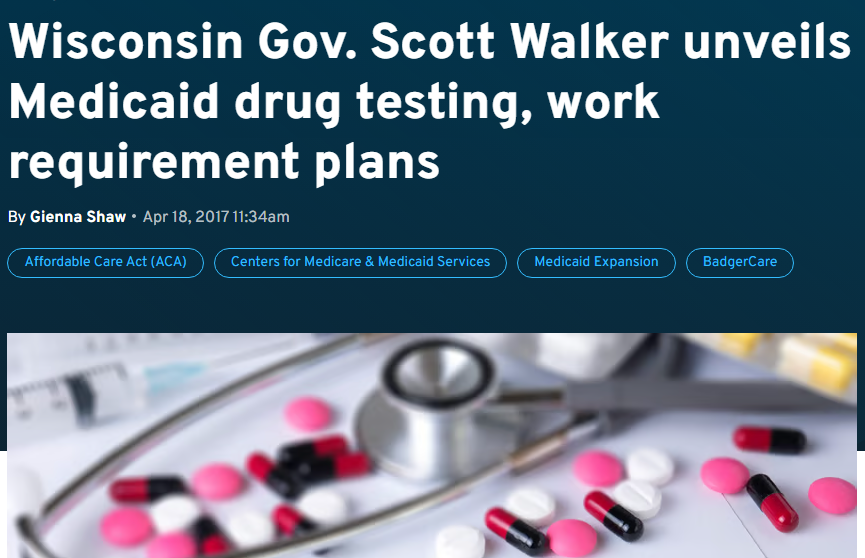

Walker pursued – and was granted – a waiver to institute work requirements and drug testing for Medicaid recipients in 2018. His loss to Evers in 2018, coupled with the pandemic just over a year, later put the waiver on hold until the Biden Administration killed it, revoking the waiver in 2021.

Walker pursued – and was granted – a waiver to institute work requirements and drug testing for Medicaid recipients in 2018. His loss to Evers in 2018, coupled with the pandemic just over a year, later put the waiver on hold until the Biden Administration killed it, revoking the waiver in 2021.

Work: The Eighth Dirty Word The Left Can Never Say

Bipartisan agreement 20 years ago built Wisconsin’s BadgerCare Medicaid Expansion around work; now work is just another 4-letter word to the left.

Consider that just before Walker took office, Democrat Doyle and the Democrat legislature were touting their plan to charge childless adults $130 a month for a stripped-down MA benefit plan. Two years later Democrats were wailing about Walker’s plan to have this same group participate in the ObamaCare exchanges where they next to nothing for private insurance coverage.

It’s also worth mentioning that having this population receive private insurance means higher reimbursement rates paid to providers than MA rates, which helps to stabilize health care costs which is better for the economy, and for health systems.

On the left, the Medicaid debate has really shifted to slamming anything that is not universal government-run health coverage.

Medicaid Today

Today’s MA is a program that spends $400 every single second of every single day in Wisconsin, and is the single largest all-funds program in the state budget.

It’s also the largest insurance plan in the state; Wisconsin taxpayers finance healthcare for the 1.6 million people on Medicaid, plus the 5% of the population that are government employees, two groups who have generally broader coverage and lower (or no) contributions or copays than they do. Taxpayers also fund the tax credits and cost-sharing of every participant in Obama’s Affordable Care Act exchanges. And on top of it all, they pay for their own health coverage.

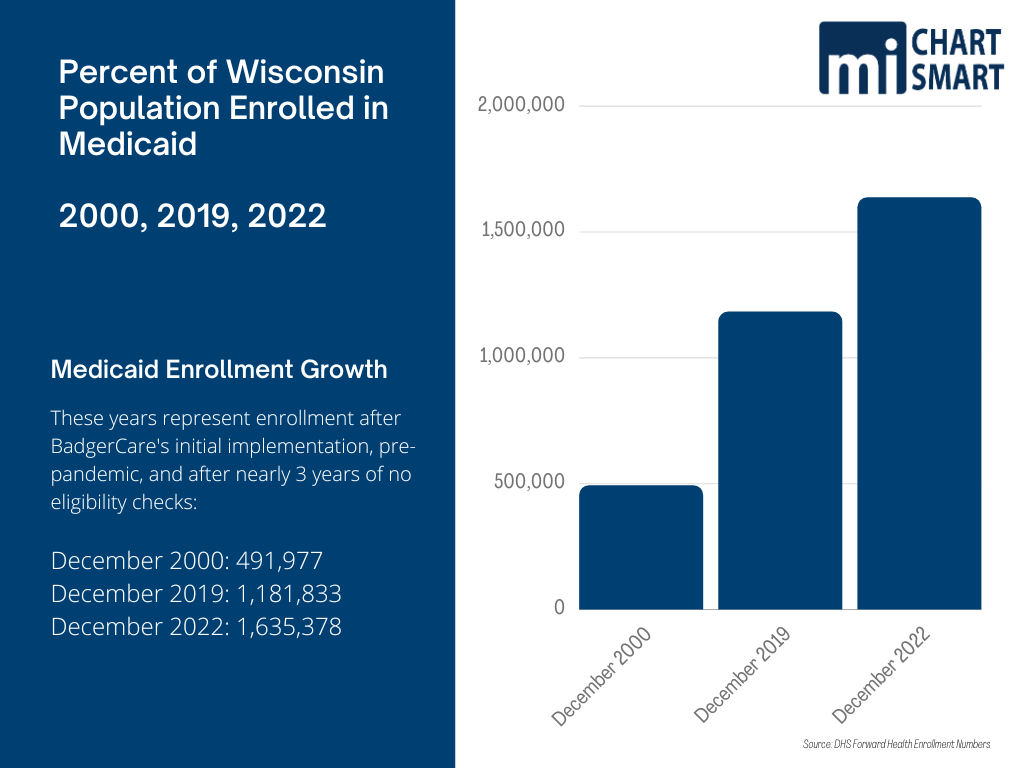

The rapid growth of our MA population started back with BadgerCare in 2000. Enrollment more than doubled by 2019 and has more than tripled today. A large proportion of the growth has been in the able-bodied, working-age, childless adult category who now comprise 18% of MA recipients.

The program created to help ensure children and working parents transitioning off welfare retained health coverage, has burgeoned into an entitlement program where taxpayers finance healthcare benefits for tens of thousands of childless adults who could work, and do not.

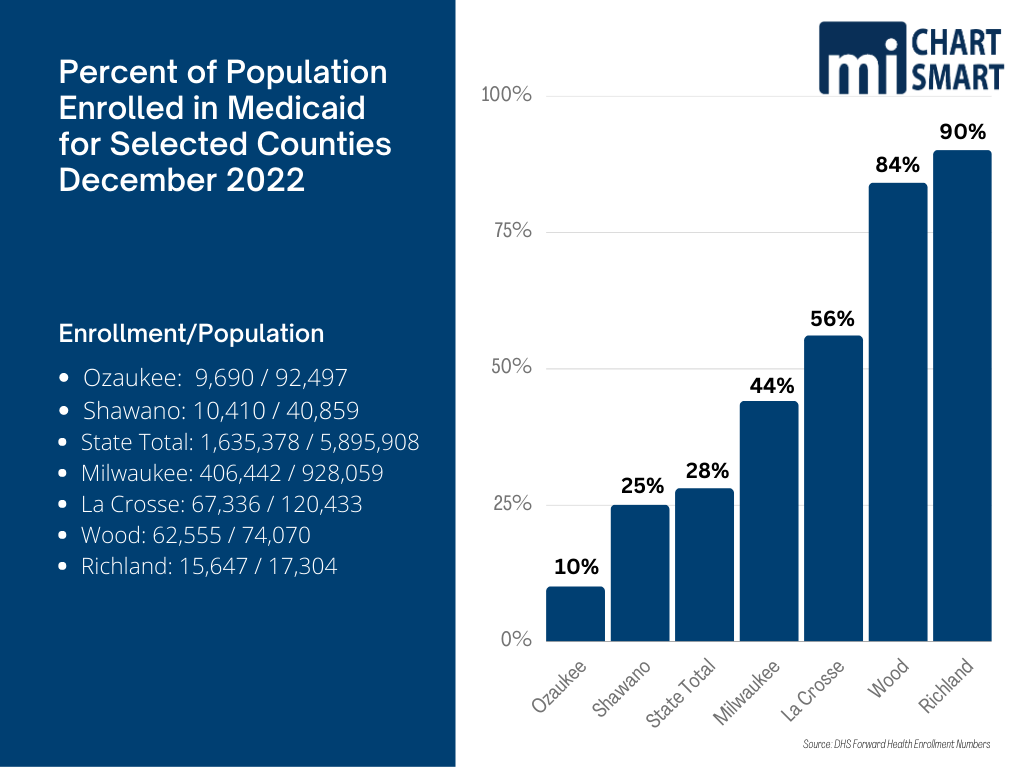

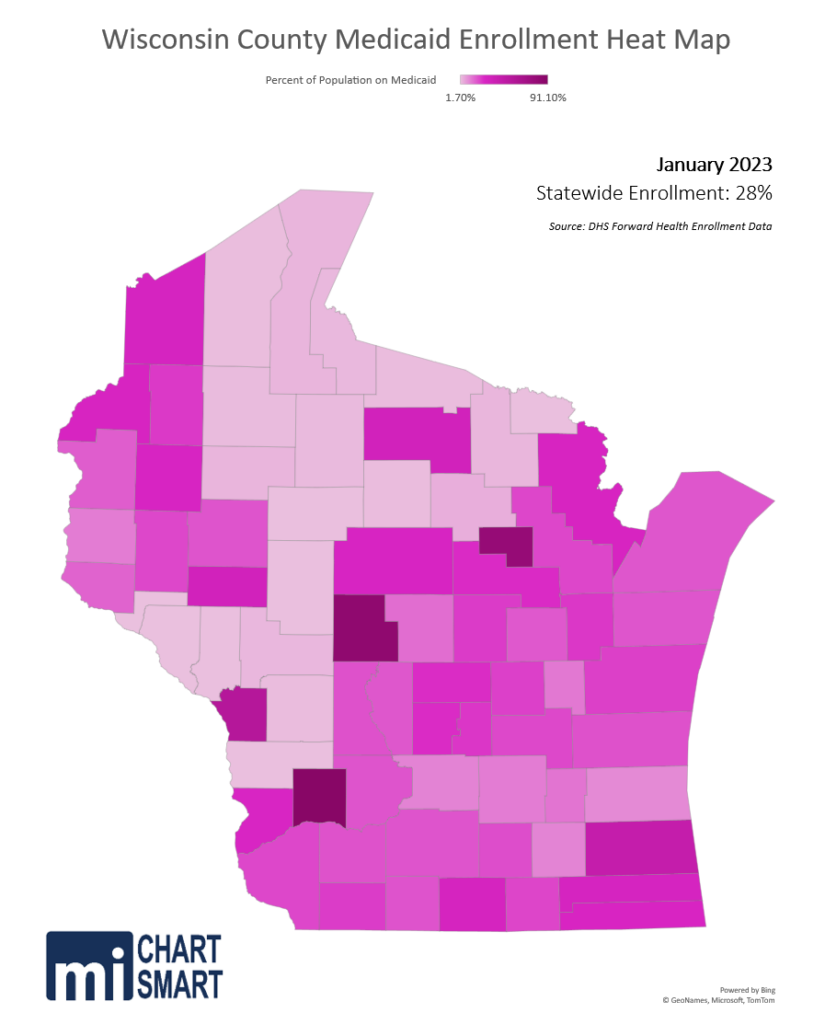

Caseloads have always varied across the state, and many mistakenly look at MA as a mostly-Milwaukee problem. There’s no question that Milwaukee recipients make up more than their share of program. The county is about 16% of the state’s population but accounts for 25% of the Medicaid enrollment; by sheer numbers Milwaukee County is a cost driver. But the county doesn’t approach the 84% enrollment in Wood County or the 90% enrollment in Richland County.

You read that correctly: 90% of the people in Richland County are on Medicaid.

Even in some of the more affluent counties with a low proportion of MA enrollees, the trends are striking. The number of Medicaid enrollees in Ozaukee County grew 49% between December 2019 and December 2022 while the number statewide grew 38%.

Uncle Sam Giveth and Uncle Sam Taketh

He Giveth

Under the pandemic health emergencies declared by the Trump Administration, two major coverage changes impacted the Medicaid program. First, the federal match rate (FMAP) was increased by 6.2%; Wisconsin typically gets roughly a 60% FMAP, and for the last three years we have gotten roughly 66%. In a program that spends just under $13 billion a year all funds, a 6% boost from the feds is in the neighborhood of $800 million dollars annually that doesn’t have to come from state coffers. But there was a catch.

He Taketh

The second major change was the requirement that states could not remove anyone from the Medicaid rolls after March 18, 2020. It didn’t matter if, or how high, their income level rose above legal ineligibility levels. It didn’t matter if they got a job that offered insurance, if they qualified for a low- or no-cost on the exchange, or if they won the Mega-bucks lottery. If someone was eligible and enrolled at any point in the past three years, they stayed on MA, and they’re still on MA. This resulted in huge growth in Medicaid enrollment across the nation.

Here in Wisconsin the MA population went from 1,181,833 in December 2019 to 1,635,378 in December 2022. That is more than 450,000 additional enrollees: a 38% increase. We went from about 20% of the state’s population on Medicaid to 28%.

The average yearly cost of MA recipients varies by age and group – children are the least expensive, the elderly and disabled are the most costly. At a rate of $7,000 each (average enrollee cost), 450,000 MA recipients would cost something like $3.1 billion per year – and with 66% (currently) picked up by FMAP, that leaves about $1 billion for state taxpayers to pick up.

Able-bodied, working-age, childless adults make up the largest portion of the increased enrollees; their numbers doubled in the past 3 years. For the first time in the history of the state we reached a point where fewer than 2 people are actively employed for every person receiving Medicaid. In January 2010 there were more than three employed workers for every recipient. The trend is unsustainable.

Planned Phaseouts and Planned Panic

States may begin disenrolling Medicaid recipients who are no longer eligible on March 31. States should have been able to begin restoring program enrollment integrity immediately since every state has had ample time and opportunity to communicate with recipients that coverage of people who no longer quality would eventually end.

That’s not happening. In 2020 CMS told state Medicaid programs they were required to develop plans to operationalize a return to normal processes; in January 2022, 41 states said they planned to take up to a year to move ineligible people off the MA rolls, and 46 states said they were ‘taking steps’ to update mailing addresses of recipients. Since states didn’t have to check eligibility, they just stopped keeping contact information for enrollees and now must track addresses down.

Unsurprisingly, Wisconsin is one of the states moving slowly. DHS plans to send one-time letters to MA recipients this month explaining a change is coming. In May 2023 the first renewal notices go out, and by May 2024 they plan to have returned to normal operations – where only legally eligible people receive benefits.

The federal government will begin phasing down the enhanced FMAP through December 2023 when it will return to normal levels – again, a financial incentive from the federal government to keep people on welfare who do not qualify. The additional (steadily decreasing) FMAP dollars will end 5 months before DHS plans to be back to normal operations. And let’s not forget, beyond the fact that Wisconsin taxpayers are the source of the federal money, our state tax dollars continue to pay for the state match.

While DHS could have started communicating with MA recipients months ago – or even all along – they did not. Instead, the initial renewals will be sent, and due, during the same 6-week period the legislature will be voting on the state budget. With so little front-end effort to prepare 1.6 million people – many of whom have not had to lift a finger to continue their enrollment for 3 years – that they must produce evidence of eligibility, a look at the DHS “unwinding” timeline looks a lot like May and June will be peppered with planned panic.

A somewhat rocky transition is entirely predictable when transitioning over a million and a half people from zero expectations to some expectations. It’s even more predictable when there has been no attempt to communicate frequently and consistently about the coming expectations.

But they didn’t lay groundwork to make sure recipients knew what was coming. Instead, when discontinuation letters arrive in mid-May after just a couple of contacts following years of silence, there is going to be confusion and uproar. DHS plans to increase staff, particularly in call centers, to help deal with the increased level of contacts and need for assistance, which certainly will be necessary. The department is unlikely to have a catastrophic failure like we witnessed at DWD’s unemployment call center, but 28% of the state’s population is on the program. There are going to be glitches, along with confused and angry people. Many of them will contact their legislators, and/or the media.

The heat map below shows the relative percent of each county’s population currently enrolled in MA. For context, Marathon County has roughly the same enrollment as the state average.

The mainstream media has already taken the position that it’s outrageous to expect people who don’t qualify for welfare to…not be on welfare. In the coming months, – even though they know there is more than a year before the rolls are dialed back to those legally eligible – they’ll treat us to overwrought stories about the thousands of people unceremoniously booted off their insurance, their cancer treatments halted, with nowhere to turn, and it will all be because the legislature won’t just expand Medicaid like the governor keeps begging them to do.

They will almost certainly not mention that the expansion population in Wisconsin is expected to number 80,000 people, only a fraction of the half a million added to rolls since 2020, perhaps because they haven’t bothered to understand expansion, and perhaps because it makes a better story if it’s left out.

COVID’s Covert Medicaid Expansion

More than a decade into the “Affordable Care Act” there are still nearly a quarter of states, Wisconsin among them, that have declined to expand. Wisconsin is unique in that we have no coverage gap; that is, low-income people in the state are eligible for either MA, or for heavily subsidized private health insurance coverage on the exchange. In many of the other states that did not expand, there are sometimes substantial gaps where a person makes too much to qualify for their own state MA program – and it’s commonly misunderstood that every state has the same eligibility requirements – but do not qualify for coverage on the exchanges.

A note about why the “Affordable Care Act” exchanges do not allow people below FPL to obtain subsidized, even free, private coverage: ObamaCare was rather cynically designed to exclude them, in order to push states to expand MA and put more people on welfare. In other words, people living in poverty were considered acceptable collateral damage by the left in the broader goal of moving toward universal, government-run health care.

Expansion is commonly misunderstood, and often deliberately misrepresented. Expansion does none of the following things:

- It doesn’t cover more children.

- It doesn’t cover more elderly people.

- It doesn’t cover more disabled people.

- It doesn’t increase or expand the benefits covered by the program.

Expansion only adds a population that was not previously covered to the existing benefit package. In some states with much less expansive eligibility limits, the expansion population was hundreds and hundreds of thousands of people.

Expansion in Wisconsin would only extend coverage to two groups both of which are eligible for heavily subsidized private insurance plans in the exchange (insurance plans that pay higher reimbursement rates to providers helping to stabilize insurance costs):

- Able-bodied, working-age, childless adults earning above the federal poverty level (FPL) but under 138% of FPL. This population would be eligible to receive the much-touted enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) rate of 90% (rather than the current ~60%).

- This is the group the ballot measure will ask about on April 4.

- This population could and should be working in a 3% unemployment economy. This is not a minimum wage problem, it’s an unwillingness to work problem.

- Only 1.6% of Wisconsin workers earn minimum wage or lower (most of them 16-24 years old); 28% of the population is on Medicaid.

- In order to qualify for MA, an able-bodied working age adult would need to limit their work to just 2 days a week in a desperately needed certified nursing assistant position, earning the state-average $19/hour starting salary in a $39,000/year full-time job.

- An able-bodied, working-age, childless adult would have to reject full-time employment at a $16/hour, $33,000/year full-time warehouse job, and choose to work only half-time or less in order to qualify for MA.

- Able-bodied parents and caretakers with income between 100-138% FPL. This population would not be eligible for enhanced FMAP and would be covered by the normal 60/40 federal/state split. Note: Children are covered in households with income up to 300% FPL; in this group, expansion would only add the working-age, able-bodied parents.

- According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ report on family employment (across all income levels):

- In 2019, 91% of families with children had at least one parent employed; post-pandemic, that has dropped to just 89%.

- In other words, in 11% of families with children neither parent is employed.

- In families with children under 6, 36% of single moms are unemployed.

- The labor force participation rate among parents is also down about a percent from 2019 for both mothers and fathers of children under age 18.

- This means fewer parents are looking for employment at all, and of those in the labor market, there are fewer working despite the low-unemployment rates.

- The availability of generous welfare benefits has made it not only appealing, but comfortable not to work. Coupled with the previously discussed decreased willingness to work, enrollment has grown.

- In 2019, 91% of families with children had at least one parent employed; post-pandemic, that has dropped to just 89%.

- According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ report on family employment (across all income levels):

The Wisconsin expansion population, able-bodied, working-age adults, was estimated by the Legislative Fiscal Bureau to be about 79,000 for 2021-22. That’s about 1/6 the number of people who have been added to the Medicaid rolls since Evers took office.

The federal government had approved the Walker Administration’s plan for a Medicaid Community Engagement requirement – work, school, training – for able-bodied childless adults in 2018. Evers was charged with implementing the program, but Democrats are lockstep in opposition to work requirements even for those with no barriers to work, and even when employers are desperately seeking employees.

The pandemic ended up saving the Evers Administration from slow-rolling implementation of the work requirement. The Trump Administration paused implementation in March 2020 due to the pandemic shutdown and spike in unemployment. The Biden Administration withdrew the approval in April 2021, ending the work requirement in Wisconsin.

This provides context for voters as they answer the April 4th ballot question. Should some people work to provide welfare benefits for a growing group of able-bodied childless adults who choose not to work?

Juiced FoodShare Benefits

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) known as FoodShare (formerly Food Stamps) is federally funded and state-administered and provides benefits to about 1 in 12 Wisconsinites. Typically, families making under 200% of the federal poverty level are eligible, but unlike Medicaid, there are income disregards for things like utilities. A family of 4 can earn $53,000 and qualify for FoodShare.

During the national pandemic Emergency, which ended days ago on March 1, Foodshare benefits were increased, to account for loss of earnings in low-income working families forced out of work by the shutdowns. Benefits were increased for each household a minimum of $95 per month, but for many the increase was much, much higher. The sliding scale was thrown out and every household was given benefits to the maximum of the range for their family size. Estimates put the average pandemic add-ons at about 34%.

The increased benefits have long outlasted the pandemic spike in unemployment and this month, benefits that are returning to normal levels after the temporary boost. Of course, the mainstream media and recipients are characterizing this return to normal as heartless and cruel cuts aimed at mass starvation.

Lacking in these Sturm und Drang stories is mention of the fact that in mid-2021, the Biden Administration instituted the largest permanent increase to FoodShare benefits in history. These increased benefits were piled on top of the already-juiced pandemic. So, when benefits go back to “normal,” they will in point of fact be 27% higher on average than pre-pandemic levels.

ABC News recently featured a Wisconsin family from Marshfield on their national coverage of “cuts” coming to SNAP benefits as the temporary increases end. This family of 4, 2 adults, 2 children saw their benefits increase from $200 a month to over $900 a month because of the pandemic add-on. Now their benefits will go down based on their income. ABC failed to mention the 27% average base increase that means their benefits will be substantially higher than pre-pandemic. The family said they wouldn’t be able to afford fruit and vegetables any longer and would be forced to buy pasta.

Criticism of benefits that are meant to be a helping hand, not a way of life, is becoming more common.

Wisconsin Public Radio produced a story last summer featuring a 39-year-old woman who had been on FoodShare for 15 years, since she was 24, complaining the benefits are not generous enough and limit her food choices. She expressed disgust at stories she had heard about Food Stamp recipients being provided surplus cheese (the first Food Stamp program was designed to provide surplus food to those in need which is why the program is run by the US Department of Agriculture). She says lower FoodShare benefits cause her physical problems, making her tired and negatively impacting her digestion.

WPR did mention Biden’s 27% base increase in this story but followed it by tying Republican efforts to reinstate the work requirement to increased food insecurity. Yes, really. Work. Driving food insecurity.

Work and FoodShare

FoodShare’s work training program in Wisconsin, FSET, has had a part-time work requirement for able-bodied adults 18-49, with exemptions for households with children, for those who are caregivers, on unemployment, in school, or in treatment for drug or alcohol addiction. FSET requires 80 hours monthly of work, or work training, for childless adults 18-49, and was the state’s largest job training program.

But the work requirement has been waived since October 2020 as part of the federal government’s pandemic efforts, and despite low state unemployment numbers has not been reinstated. The waiver does not expire until September 30, 2023, and it’s likely the Evers Administration will ask for a further extension from the Biden Administration, so it’s possible – even likely – this could be extended further.

Given the unwillingness to allow work requirements for able-bodied childless adults in Medicaid, it is clear both the Evers and Biden Administrations will do little if anything to move able-bodied workers from the dole to the workforce.

Work, Welfare and Wisconsin

Welfare, as many feared back in the 80s – when a far smaller percent of the population was government-dependent – has become an entrenched, generational way of life.

Work, on the other hand, is increasingly being considered optional and unnecessary. You have only to read stories about the “great resignation” or talk to friends and family with grown unemployed children still living at home, check out the low labor force participation rate and the low employment rate of the able-bodied, working-age adults on welfare to see this. In the past 25 years Wisconsin’s population has grown 13%, but the number of employed has only increased 5%, even with near-historic low unemployment.

The left sees any suggestion that people who can work should work, as meanness, racism and insensitivity.

Our current level of work-avoidance and welfare-adherence is not sustainable and moreover, not fair to the working taxpayers who not only pay their own way, but increasingly pay the way for more and more people who could be doing the same.

The right has often been complicit in the increase in welfare dependency. Part of it is the fear of being labeled cruel, and part of it is an increasing susceptibility to sad stories, and we also see it in things like wanting to eliminate “fiscal cliffs.” A ‘fiscal cliff’ is a term the left has used to great effect that simply means “eligibility limit.” Welfare programs need to have a cutoff, or everyone is eligible for welfare. Eliminating fiscal cliffs is code for expanding eligibility, and the right has either not fully recognized this or is happy to go along with the expansion.

There is nothing wrong with expecting able-bodied people to work, even less wrong with expecting them to work if they want to receive welfare benefits funded by the sweat of the brows of people who do work.

In April, voters have the opportunity to weigh in on whether they want able-bodied childless adults to get into the workforce if they want to receive taxpayer-funded welfare benefits. We at MacIver believe they should.

But that vote is only part of the state and national discussion that will be in the headlines over the coming months on the issue of welfare, welfare benefits, and the cost to taxpayers of the dependence of a growing number of welfare recipients who increasingly treat welfare as a way of life rather than temporary help in a time of need.