[bctt tweet=”Here’s what tax-and-spend Madison should have learned from its failed broadband-for-all initiative: Big government has no business in the private sector Internet space. #wiright #wipolitics” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”Here’s what tax-and-spend Madison should have learned from its failed broadband-for-all initiative: Big government has no business in the private sector Internet space. #wiright #wipolitics” username=”MacIverWisc”]

MacIver News Service | June 15, 2018

By M.D. Kittle and Chris Rochester

MADISON, Wis. – The city of Madison spent a half million dollars of taxpayer money on a failed pilot program to bring broadband to four low-income neighborhoods.

So what did bureaucrats learn from this crash-and-burn experiment?

“I had this fear that we were trying to solve a problem that maybe didn’t exist,” committee member Tom Mack said Thursday at a DTC meeting.

Not nearly enough, it seems.

“It is these lessons learned from the Digital Divide Pilot Project that will assist us in laying the foundational pieces for a stronger contract with the City of Madison’s next ISP (Internet Service Provider) partner,” sanguinely declares a “Lessons Learned” report (a thin four pages at that) from the city’s IT staff.

What these seemingly unfazed bureaucrats should have learned is that the pilot program and a broader, $173 million, city-owned broadband network is a huge waste of taxpayer money. It’s also an unnecessary pursuit in a highly connected city in which private broadband providers are already offering low-cost, high-speed internet options.

Some members of the city’s Digital Technology Committee get it.

“I had this fear that we were trying to solve a problem that maybe didn’t exist,” committee member Tom Mack said Thursday at a DTC meeting.

Committee member Samba Baldeh summed up the botched pilot program.

“A half million dollars for almost zero results,” he said.

In the end, the ISP partner that won the contract to lead the pilot program signed up just 19 customers out of a total of 979 potential subscribers in the low-income neighborhoods. Two of those subscribers were dropped for nonpayment, according to Herb King, technical services manager for the city’s Information Technology department.

“Only 1 percent of subscribers participated in the Digital Divide Pilot,” the “Lessons Learned” report forlornly notes.

The report’s recommendation for next time? Ask the residents of the neighborhood if they have any interest in the service. It evidently didn’t occur to anyone shepherding the project to ask questions like this first.

One of the big issues, according to the report, was the low count of signed rights of entry. The contractor could not secure any operational rights in the Kennedy Heights neighborhood, and only 50 percent in the Brentwood and Allied Drive neighborhoods. Turns out, the low-income neighborhoods already had contracts with other broadband providers.

Committee member Samba Baldeh summed up the botched pilot program: “A half million dollars for almost zero results,” he said.

That’s probably something the players in this doomed government-led partnership should have have known before going in.

The recommendation moving forward is to “perform an analysis of the neighborhood property owners’ willingness to allow other vendors to provide service.”

Mack said rights of entry should have been a significant consideration going in.

“Those things warrant more insight in this, what we as a committee give to the council or whoever this goes to,” he said. “It concerns me that all these lessons learned, the cost estimates, the plan, and providing wireless and that. You can get all those right next time and still have a 1 percent subscription rate. So you will have done the project perfect, but you won’t have accomplished anything.”

Mack asked the city’s techies if they looked at existing options in the marketplace and their costs, and whether they reached out to the property owners involved. They didn’t.

“I just feel that’s a kind of fundamental analysis before” launching an initiative. “I don’t see that as a big endeavor…making a few phone calls.”

In 2015, ResTech Services, a private telecom provider, was tapped to lead the pilot. Expected to reach hundreds of underserved customers through the city’s subsidized broadband-for-all initiative. It didn’t go so well.

The “Lessons Learned” report criticizes the vendor for not having a “clear project plan.” ResTech, according to the IT crew, failed to clearly define the project schedule, and they found the vendor’s communication skills lacking. At a meeting in April, committee members noted, without going into much detail, ongoing litigation in the matter.

ResTech President Bryan Schenker told MacIver News Service last year that the biggest challenge was trying to bring broadband to apartment complexes that already have service agreements with other providers, particularly exclusive agreements. He called it a “competitive barrier,” but those providers simply got there first.

Schenker said those fixed positions were “something people didn’t generally understand” going into the test. The “people” in this case would be common council members and bureaucrats.

Some basic economic principles seemed to have been lost on the Internet-for-all crowd. They weren’t lost on ResTech.

“One of the challenges we run into as an industry is how to figure out how to pay for and service low-income residents,” Schenker said. “If it was just a matter of economic interest why would ResTech or any provider invest in low-income properties?” It’s a return-on-investment question. And that’s why such markets are underserved.

In true big government boondoggle form, other issues raised in the report include project delays, electronics not delivered in a timely manner, work on the fiber optic network not being completed on time, low-balled cost estimates, and lack of access to wireless modems. Add to that another concern raised by committee members: lax oversight by the city’s teeming IT bureaucracy.

The city also conducted a mail-in survey of the 19 subscribers in the pilot project. Five surveys were returned, all generally giving the service high marks. At $100,000 per returned survey, that was at least one bright spot.

It’s no shock that the pilot had so few takers. Broadband experts say Madison is one of the most digitally connected cities in the country, thanks to the private sector, not the government. An earlier survey found that about 95 percent of city respondents had some form of Internet connection, with 89 percent reporting home Internet service.

IT staff members eager to put the pedal to the metal on a city-owned broadband network struggled to counteract the growing feeling among committee members that the project is a disaster waiting to happen.

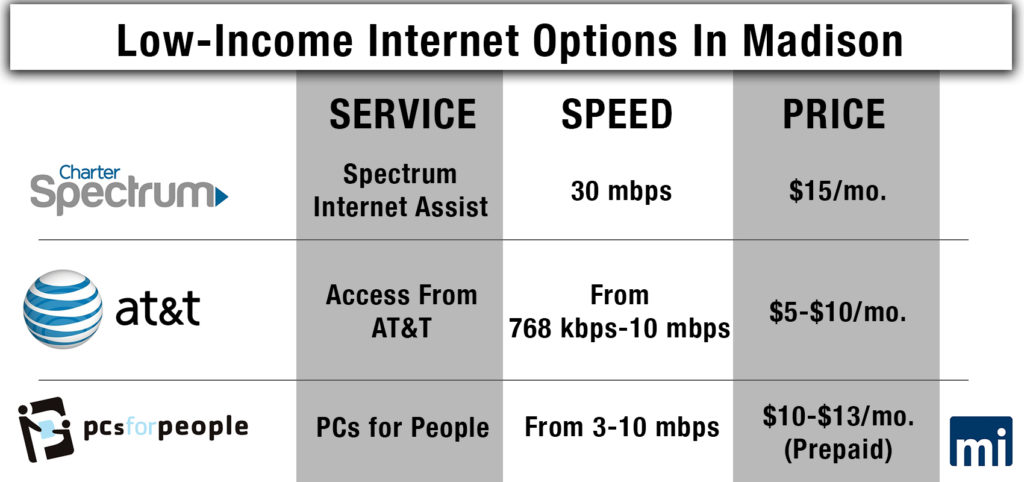

And in recent years, private providers have rolled out low-cost, high-speed broadband service aimed to serve the low-income populations city leaders say they want to help. In Madison, AT&T and Charter Spectrum both offer service options for low-income households.

IT staff members eager to put the pedal to the metal on a city-owned Fiber to the Premises (FTTP) broadband network struggled to counteract the growing feeling among committee members that the project is a disaster waiting to happen.

Just last week, members of a Digital Technology subcommittee got a cold shot of fiscal reality when they heard a price estimate from CTC Technology & Energy, the consultant contracted to track projected costs of a proposed “Fiber To The Premises” project that builds off the failed pilot.

The estimated expense to build a so-called “dark fiber” FTTP network that “passes each residence and business” in Madison, is estimated to cost north of $150 million – $173.2 million all told when bonding costs are added in, CTC said.

And even in the rosiest scenario of Madison residents flocking to sign up, most of the funding would have to come from assessments on properties. Ben Chase, CTC staff engineer, said none of the bids from the private broadband service providers interested in partnering with the city “would cover the entire bonding amount.”

None comes close, according to the report. Private provider fees to link high-speed Internet service to customers who seek it would bring in about $52 million, less than a third of the total cost for the built-out alone.

The remaining $121.2 million would have to be paid for by assessments, socking taxpayers with a massive bill for a service nine out of ten residents already have.

Madison’s ultra-liberal mayor Paul Soglin could be an unlikely roadblock for the broadband boondoggle. He recently came out with budget instructions urging spending restraint. In the instructions to city department heads, issued in May, Soglin notes the city’s general obligation debt has more than doubled over the past 10 years and debt service has “increased much faster than the overall budget.”

“Projects that extend the life of or replace existing infrastructure should be given higher priority over new facilities and projects that increase operating costs,” the mayor advised department leaders.

Soglin didn’t respond to MacIver News Service’s question: Does he believe ubiquitous, city-owned broadband is a “higher priority?”

Several members of the Digital Technology Committee are beginning to wonder.

Any proposal to move the costly fiber project to the full City Council has been pushed back to October.