And taxpayers are left picking up the pieces

There are plenty of cautionary tales about the failures of city-owned broadband networks around the country. Will Mayor Soglin and city leaders in Madison learn from them?

MacIver News Service | Aug. 17, 2018

By M.D. Kittle

MADISON – Mayor Paul Soglin’s broadband-for-all vision turned into another big-government nightmare in the light of some hard fiscal reality.

Earlier this summer, Madison’s Digital Technology Committee learned just how much a city-owned broadband network would cost, and it wasn’t pretty.

The estimated expense to build Madison’s broadband network is expected to cost north of $150 million – $173.2 million all told when bonding costs are added in.

The estimated expense to build a so-called “dark fiber” Fiber to the Premises (FTTP) network that “passes each residence and business” in Madison, is expected to cost north of $150 million – $173.2 million all told when bonding costs are added in, CTC Technology & Energy, the consultant contracted to track projected costs of the proposed project, said.

More so, an expensive pilot program that was supposed to bring city-led, low-cost, high-speed internet service to four low-income neighborhoods failed miserably, signing up a paltry 1 percent of participants.

“I had this fear that we were trying to solve a problem that maybe didn’t exist,” committee member Tom Mack said at a meeting of the City Council’s Digital Technology Committee in June.

The meeting focused on “Lessons Learned” from the city’s expensive experiment thus far. What Madison’s bureaucrats should have learned after three years of studies and disconnections is what so many taxpayers in communities across the country already know: Municipal broadband is a very costly endeavor, often unnecessary in communities like Madison that are already highly connected thanks to private sector broadband providers.

A cautionary tale

A 2017 analysis by University of Pennsylvania professors Christopher Yoo and Timothy Phenninger, “Municipal Fiber in the United States: An Empirical Assessment of Financial Performance,” examined scores of city-owned FTTP systems. The findings offer a cautionary tale to communities like Madison.

“These results suggest that municipal leaders should carefully consider all of the relevant costs and risks before moving forward with a municipal fiber program,” the study’s executive summary asserts. “Underperforming projects have caused numerous municipalities to face defaults, bond rating reductions, and direct payments from public coffers.”

Beyond the fiscal issues, the study’s authors note, troubled municipal broadband ventures “take a toll on community leaders in terms of personal turmoil and distraction from other matters important to citizens.” In other words, such costly projects, despite the insistence by some that high-speed internet service is an inherent right of all citizens, take away time and capital from traditional government priorities and critical services.

To be sure, the analysis has its critics, particularly from think tanks and other institutions that have long advocated for government-led broadband projects. Blair Levin of the Brookings Institution took particular aim at some of the study’s findings, declaring it “swings and misses on communities and next generation broadband.”

Perhaps the biggest complaint from municipal broadband advocates is that such government projects aren’t about profits.

“Cities invest in many facilities that are not designed to make a profit, from sports stadiums and convention centers to airports and museums,” Levin wrote. “Cities are not indifferent to the economics of such projects, but the bottom line is not strictly enterprise solvency.”

But shouldn’t profitability, at least return on taxpayer investment, be at the top of the government goals list?

Yoo’s and Phenninger’s study, among others, outline too many cases where taxpayers have been burned by municipal fiber projects that have turned out to be far from solvent or sustainable.

Bad bets

As of 2016, more than 450 communities were estimated to have some form of taxpayer-funded, government-owned internet service, including more than 80 cities with large-scale FTTP broadband networks, according to the Taxpayers Protection Alliance. The nonpartisan group, according to its website, is in the business of educating the public about “the government’s effects on the economy.”

TPA, like most free-market organizations, has been attacked by the left as being a front group for big business. The nonprofit asserts that its goal is to hold politicians and government officials accountable for the impacts of their policies.

The city had secretly loaned $16.9 million to Burlington Telecom, which the provider failed to repay. A credit downgrade followed, as did a lawsuit from Citibank seeking damages north of $33 million.

TPA’s most recent report on government-owned broadband networks, “The Dirty Dozen,” hammers what it sees as the biggest offenders of the taxpayer’s trust and money.

“Construction costs for broadband networks frequently go over budget, customer subscription numbers rarely meet projections, bonds used to finance the projects often strain budgets for decades, credit ratings often plunge as a result of fiscal difficulties related to the projects, and quickly changing technology often leaves the networks obsolete after just a few short years,” the TPA 2016 report states.

Topping the list of the “Dirty Dozen” is Burlington Telecom, the debt-ridden, government-owned Internet network of Burlington, Vt. Taxpayers were buried in millions of dollars in debt after the municipal system’s profits began to dry up a decade ago.

In 2009, the city was forced to admit it had a debt problem. It had secretly loaned $16.9 million to Burlington Telecom, according to reports. The public Internet provider failed to repay. The massive, secret bailout led to the resignation of the city’s chief financial officer.

A credit downgrade followed, as did a lawsuit from Citibank, seeking damages north of $33 million. Eventually, in 2014, the city agreed to sell Burlington Telecom and split the proceeds to pay of its debt. That sparked an internecine war among government officials and some taxpayers, who earlier this year fought the sale to a private company.

“Waste and misuse of the City’s resources will result if the Petition is granted,” a lawyer for the group wrote in March. Waste and misuse has already long dogged the government-owned network.

The University of Pennsylvania study found several municipal broadband systems generating negative cash flow in the five-year assessment period.

“Unless these projects substantially improve their performance, they will not be able to cover the costs of current operations, let alone generate sufficient cash to retire the debt incurred to build the project,” the analysis states.

Many have been forced out of the market. Marietta, Ga., for instance, sold its $35 million broadband system for $11.2 million, a loss of $24 million. When the dust settled on the municipal network failure, Marietta’s mayor admitted the investment was a bad idea.

Provo, Utah, ended up selling its system for a buck to Google after launching the failed municipal system on the back of $39 million in bonds.

Provo, Utah, ended up selling its system for a buck to Google after launching the failed municipal system on the back of $39 million in bonds. Quincy, Fla., racked up $5.1 million in debt and another $56 million in operating losses before shifting ownership of its system to a private provider. And the list goes on and on.

There are very good reasons why so many communities have gotten out of the broadband business and transferred ownership to for-profit internet service companies. The private sector, simply put, can build, expand, and maintain broadband more efficiently and effectively than government can.

Even the big-government argument of broadband equity is disappearing.

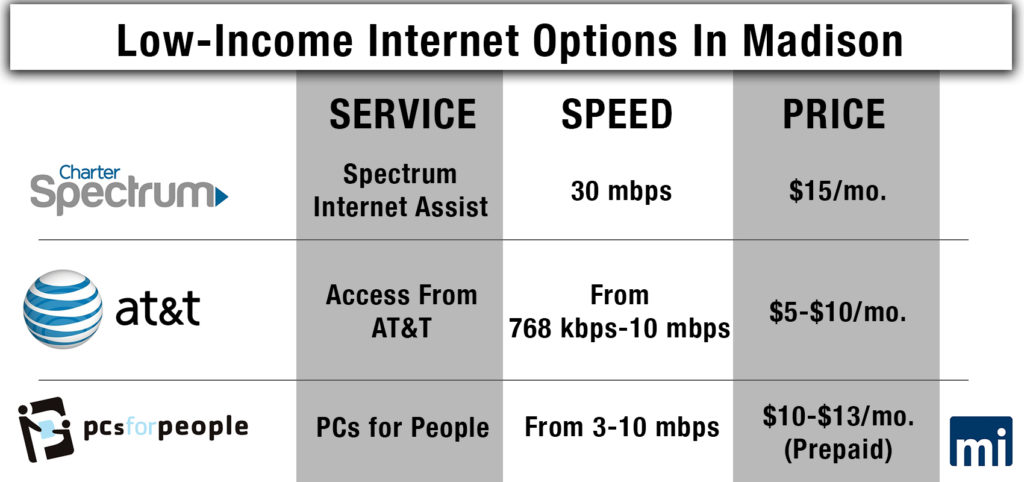

In recent years, private providers have rolled out low-cost, high-speed broadband service aimed to serve the low-income populations city leaders say they want to help. In Madison, AT&T and Charter Spectrum both offer service options for low-income households.

The Sun Prairie problem

You don’t have to travel too far from Madison to find examples of municipal broadband failure.

In 2017, Sun Prairie, a suburb of Madison, sold its costly fiber system to TDS Telecommunications Corp. for $2.88 million, just a bit more than the city’s outstanding debt on its assets, according to the Wisconsin State Journal. Madison-based TDS announced it would build a FTTP network with 1 gigabit-per-second downloads speeds to serve Sun Prairie area residents.

The private sector, simply put, can build, expand, and maintain broadband more efficiently and effectively than government can.

Sun Prairie Utilities built the broadband network’s first fiber ring in the late 1990s, connecting city buildings and public schools. The seed money – $600,000 – came from a loan from the city’s electric utility.

The network, which made the Taxpayers Protection Alliance 2015 map of “broadband boondoggles,” was eventually built out to residential and business customers. By 2016, the network was serving customers in about 500 homes and apartment buildings and about three dozen businesses – an anemic market penetration rate of about 5 percent.

And therein lies one of the big problems for municipal broadband.

Members of Madison’s Digital Technology subcommittee got a cold shot of fiscal reality in June when they heard the price estimate from CTC Technology & Energy, the consultant contracted to track projected costs of the city’s proposed fiber to the premises project.

CTC’s model estimates a 30 percent “take rate,” the percentage of solicited customers purchasing city-based broadband service.

Even in the rosiest scenario of Madison residents flocking to sign up, most of the funding would have to come from assessments on properties. Ben Chase, CTC staff engineer, said none of the bids from the private broadband service providers interested in partnering with the city “would cover the entire bonding amount.”

None comes close, according to the report. Private provider fees to link high-speed Internet service to customers who seek it would bring in about $52 million, less than a third of the total cost for the build-out alone.

The remaining $121.2 million would have to be paid for by assessments, socking taxpayers with a massive bill for a service nine out of ten residents already have.

The remaining $121.2 million would have to be paid for by assessments, socking taxpayers with a massive bill for a service nine out of ten residents already have.

CTC’s report noted the proverbial fly in the ointment of government-controlled broadband. Madison, Chase reaffirmed, is a “mature” broadband market. An earlier survey found that about 95 percent of city respondents had some form of Internet connection, with 89 percent reporting home Internet service.

Beyond the implementation costs and market realities is what the researchers at the University of Pennsylvania described as the “emotional energy” that a struggling public broadband system can consume.

“The adverse impact of financial problems is reflected not only in a city’s balance sheet and tax rates, but also in the initiatives that are not undertaken because of city leaders’ need to focus on addressing any problems associated with broadband operations,” the report states. “Decision makers must consider the risk that a struggling municipal broadband network might consume much of their time while in office.”

The question now is, will Madison learn from the failures of others, or will they continue down this costly and risky path?

[bctt tweet=”There are plenty of cautionary tales about the failures of city-owned broadband networks around the country. Will Mayor Soglin and city leaders in Madison learn from them? #wiright” username=”MacIverWisc”]