[bctt tweet=”.@GovEvers’ 2019-21 budget: A Liberal’s Wish List, A Nightmare For The Wisconsin Taxpayer. Billions in new spending, massive tax hikes, and much more bad news. MacIver breaks it all down. #wibudget #wiright #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”.@GovEvers’ 2019-21 budget: A Liberal’s Wish List, A Nightmare For The Wisconsin Taxpayer. Billions in new spending, massive tax hikes, and much more bad news. MacIver breaks it all down. #wibudget #wiright #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

A Liberal’s Wish List, A Nightmare For The Wisconsin Taxpayer

Billions more in spending, a multitude of tax increases, hundreds of new government positions, untold amounts of borrowing to pay for it all and the roll back of nearly all taxpayer-friendly reforms.

March 4, 2019

A MacIver Institute Preliminary Analysis Based on the Budget In Brief From the Department of Administration

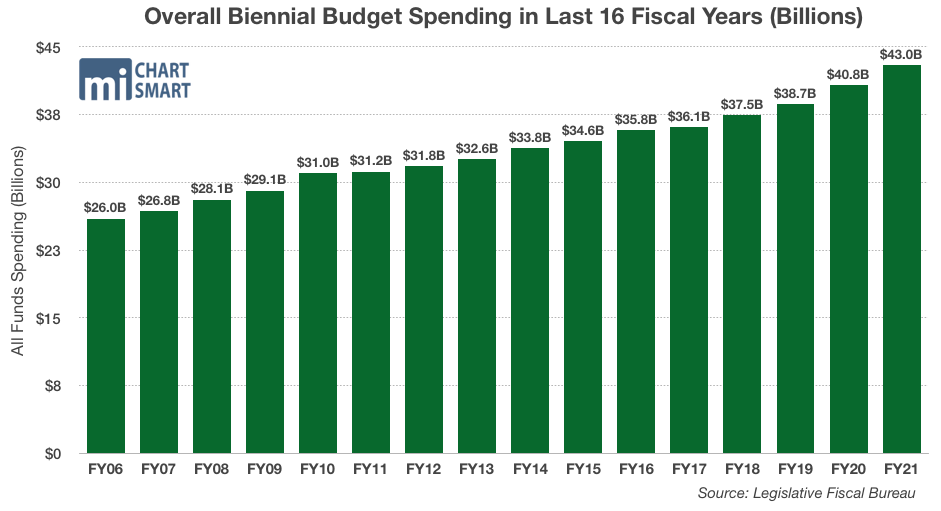

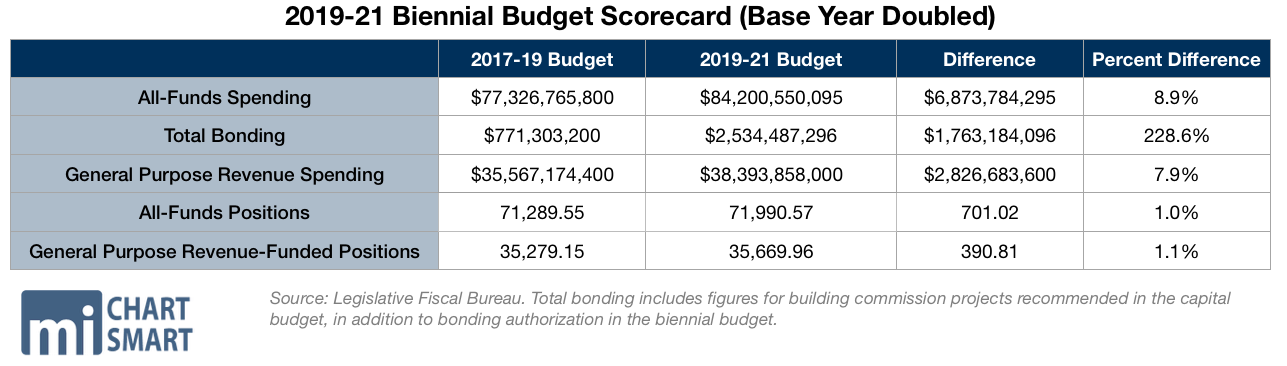

Gov. Tony Evers introduced his 2019-21 biennial budget proposal Thursday night. The sweeping document would spend $83.5 billion over two years, at least $7 billion more than former Gov. Scott Walker’s last budget.

The proposal has been described by Speaker Robin Vos as a “big liberal wish list.” Looking at the expansive list of progressive policies that vastly grow the size and scope of government, it is hard to argue with that description. From Medicaid expansion, the end of recent welfare work requirements, an unneeded increase in the state’s minimum wage, a green pipe dream to make the state carbon free, the creation of many new government programs, an assault on proven education reform programs, the decriminalization of small amounts of marijuana, to the end of the property tax freeze — this budget is full of liberal dreams. These changes, and many more that we will detail later, will be paid for with a slew of tax increases and hundreds of millions of dollars in new bonding.

While we sift through the thousands of pages of the budget document line by line, we thought it would be helpful to produce a preliminary analysis of the Governor’s budget based off the Budget In Brief produced by the Department of Administration. As the name implies, the BIB is not comprehensive and we won’t know what the total picture of this budget looks like until our exhaustive examination is complete.

Gov. Evers’ budget seeks to undo many of the reforms championed by Walker’s administration, including repealing right-to-work, restoring the state and local prevailing wage, and rolling back numerous tax protections that have led to a property tax freeze in recent years. The document claims that the property tax bill for the median value home will grow under the rate of inflation, but allowing local units of government more power to raise property taxes will most certainly negate that.

First, let’s go through the basics of spending, borrowing, and overall government positions.

The Basics

In total, the budget proposal includes a flurry of provisions that would increase property tax bills across the state. It makes income taxes more progressive by targeting more income tax relief on lower tax brackets, while increasing income taxes for higher earners. How about spending, positions, and borrowing?

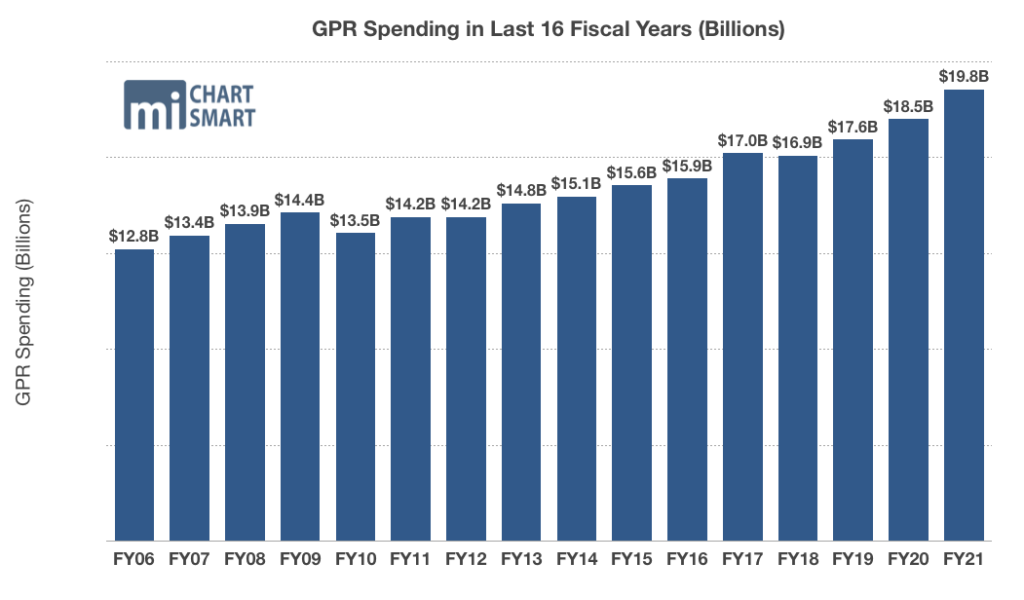

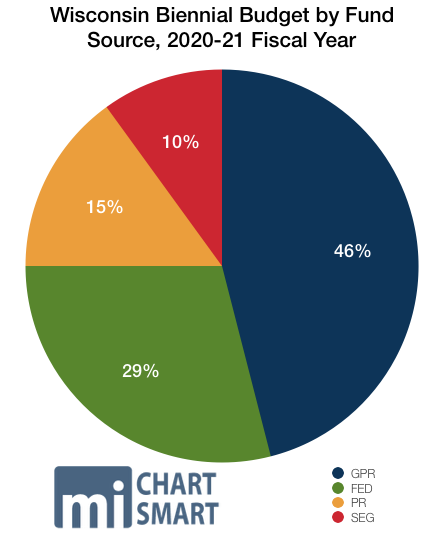

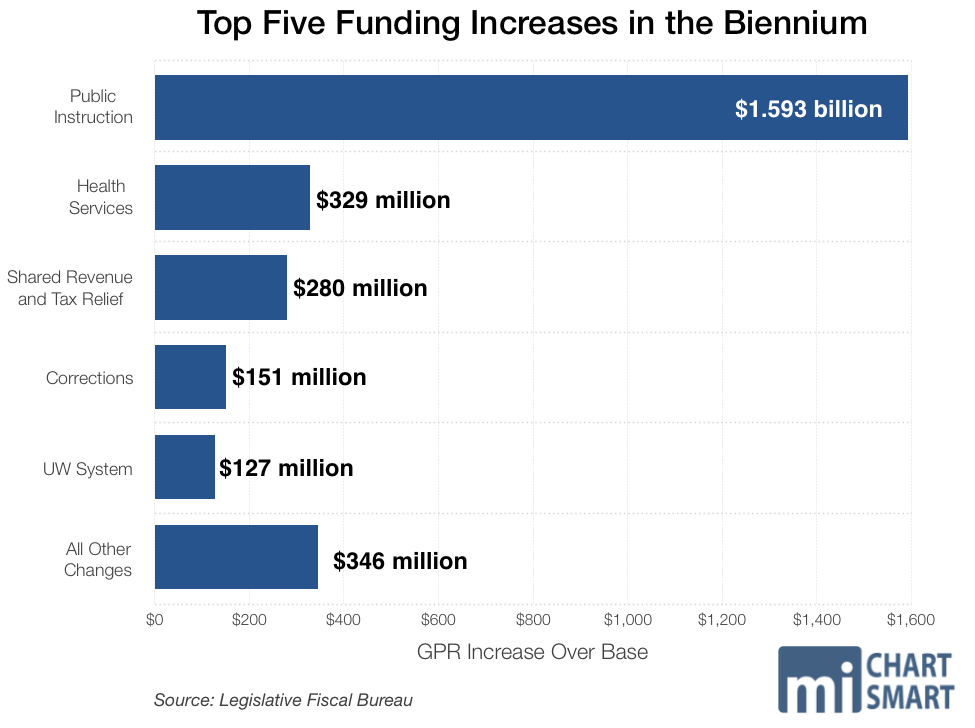

General purpose revenue (GPR) spending would increase by 7.6 percent, to $38.3 billion in the proposal, $2.7 billion more than current spending.

The budget proposal would increase total all funds positions to nearly 71,991 in the second year, a 701-position increase of government jobs from all funding sources from the current budget. GPR positions would increase to 35,670 by the second year in the biennium, a position increase of 391 from current levels.

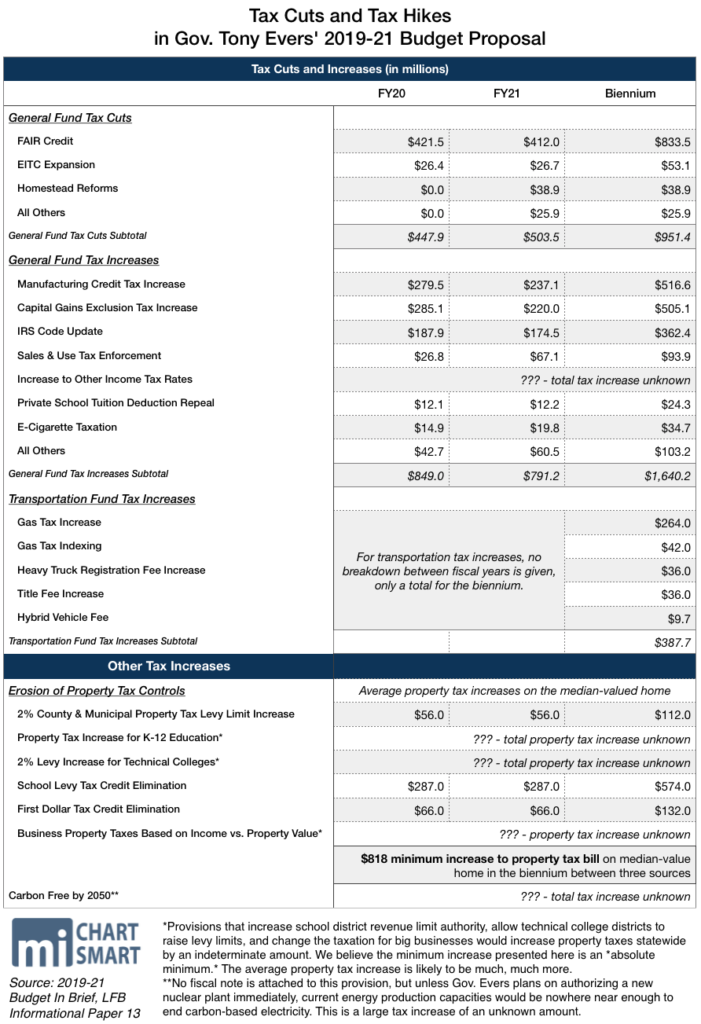

Taxes in the general fund would increase by a total $1.64 billion over the biennium. Tax cuts in that fund, including a brand new middle-class tax credit and expansion of other already-existing credits, total $951.4 million. That means in all, the net tax increase to Wisconsin taxpayers would be $688.7 million over the next two years. However, many other tax increases such as the proposed gas tax hike and removal of property tax controls will push this total much higher.

The budget uses a form of trickery called “base year doubled.” Under that method, the new base for the next budget is simply double the second year in the prior budget. In reality, base year doubled is a slight of hand trick that guarantees the constant growth of government spending.

Let’s pretend that the government spends $200 total in one budget. The first year of the budget spends $50, and the second year spends $150. You might think that the base for the next budget is $200, since that is what we spent. It’s not. The base is instead the second year doubled, in this case $300.When setting up assumptions for the next budget, it looks like we just spent more than we did, and so of course we have to spend even more. Anything less than $300 now looks like a cut, even though that’s already $100 more in overall spending. Assumptions casually shift, inflating the base cycle after cycle and fleecing taxpayers time after time. Most of the time, governments back-load more of their spending in the second year, as this document does. That means next budget, the base will be even more inflated.

We see that play out with calculations for this budget. The 2017-19 budget is counted as $77.3 billion. However, actual dollars spent paint a different picture. If total actual spending in the two previous fiscal years is added together, the total comes to $76.4 billion. In that light, the actual dollar spending increase in Evers’ budget comes to over $7 billion. Using the base year doubled method is standard, but it’s also one way that automatic growth of government is built into the state budgeting process.

The document analyzed in this piece is called the “Budget In Brief” and does not include the statutory, legal language that would eventually become law if approved by the Legislature. That’s why some dollar figures, such as overall bonding, are unclear.

However, the full budget document, which we are still examining line-by-line, shows that the budget proposal would increase borrowing by more than $440 million in the biennium. That includes borrowing for a number of conservation projects as well as roads.

The Governor’s capital budget adds another $2.5 billion in bonding. That recommendation is more than double the average borrowing amount, $1.157 billion, from 2011 through 2019. We wrote about the capital budget in detail here.

Other provisions may not be highlighted within the Budget In Brief but will become clear in the weeks and months to come. The most curious among these is an apparent lack of reference to Walker’s signature 2011 reform, Act 10, which was repeatedly slammed by the now-Governor on the campaign trail and in years past. Nowhere does the Budget In Brief seek to roll back taxpayer protections created by the law, including increased contribution levels for public sector employee benefits or annual union recertification votes.

The Legislative Fiscal Bureau has begun its work translating the Budget In Brief to a more formal analysis, which will be published by the end of the month. After that, the Joint Finance Committee will get to work parsing through the document, agency by agency.

*April Editors’ Update: LFB has now published its fiscal analysis of the document. Major charts in this piece have been updated to reflect that work. See more with ChartSmart here.*

Tax Increases, Tax Cuts

Evers’ budget proposal introduces myriad tax hikes to at least partly pay for massive spending increases. First on the docket is a tax increase introduced by his office several weeks ago — a partial rollback of the Manufacturing and Agriculture Tax Credit (MAC). That change would limit the job credit for manufacturers to the first $300,000 of qualified income. The move would raise $516.7 million in tax revenue over the biennium by raising taxes on those manufacturers.

According to one recent analysis by the Tax Foundation, nearly 70 percent of Wisconsin manufacturing firms pay the individual income tax rate instead of the corporate tax rate. Since those companies are organized as pass-through businesses, all of their business income is taxed as individual income.

In other words, a manufacturer who earns $300,000 or more may appear to be part of Wisconsin’s upper-echelon of earners — but all of that business-owner’s equipment and inventory is included in the figure. As Joint Finance Committee co-chair Sen. Alberta Darling (R-River Hills) recently said on the Senate floor, “You know a farmer is dealing with a budget that might be 1, 3, 5 or 6 million dollars. They’re not taking that money home. Those are just the expenses they have to deal with.”

Another change would increase the long-term capital gains tax. Under current law, long-term capital investment gains are taxed at a 5.355 percent rate. The budget proposal removes part of an existing exclusion, so that those gains are taxed at the top individual income tax rate of 7.65 percent for certain earners. Individuals earning less than $100,000 and married-joint filers earning less than $150,000 would keep paying the capital gains tax at the 5.355 percent rate, while earners above them would move to 7.65 percent.

[bctt tweet=”#wibudget: If a retiree cashes in a stock they’ve held for years, those earnings will again be taxed at the highest rate available, punishing taxpayers who are successful or preparing for retirement to the tune of $505.1M more in taxes.” username=”MacIverWisc”]

If a retiree cashes in a stock they’ve held for years, those earnings will again be taxed, this time at the highest rate available. That move punishes taxpayers who are successful or preparing for retirement to the tune of $505.1 million more in taxes.

Evers’ budget plan includes changes to align Wisconsin to federal law under the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The state would close nearly all divergences with federal law, raising tax collections by $362.4 million.

Two dozen new auditors would be hired by the Department of Revenue, alongside 12 compliance-related positions. Those new hires would be charged with collecting any taxes already owed but not yet collected by the state, raising an estimated $36.4 million over the biennium.

The proposal would also extend the cigarette tax to e-cigarettes and related vapor products, arguing that the new technology amounts to a substitute that should be taxed the same way. That change would raise taxes by $34.7 million over the biennium. “Cigarillos,” or little brown cigars, are targeted in a similar manner, with a proposed tax increase on the brown cigarettes of $6.8 million.

Other tax increases include a change to the taxation of out-of-state broadcasters, who would see $29.5 million more in taxes over current levels. The deduction for private school tuition would also be eliminated, raising $24.2 million for the state in the biennium.

Late in his campaign, Evers announced plans for a 10 percent tax cut on the middle class. On Thursday, the public saw specifics for the new tax credit for the first time. The administration is proposing a tax credit called the Family and Individual Reinvestment (FAIR) credit. Individuals earning below $80,000 and married-joint filers earning below $125,000 will receive a tax credit of 10 percent of their net tax liability or $100, whichever is greater. The credit phases out at $100,000 for single earners and $150,000 for married-joint filers.

That amounts to $833.5 million in income tax cuts over the biennium. The average recipient of the credit would see an annual income tax cut of $217, while the median family of four could receive more than $500 annually.

Another new tax credit would be created for child and dependent care, beginning in the second year of the budget. That credit would be 50 percent of the same credit available federally. The same year, the tax deduction for child care would be eliminated. That change adds up to $10 million in tax cuts annually.

Other tax cuts targeted at low- and middle-class earners are expansions on already-existing programs. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) would be expanded so that filers with one dependent child could claim up to 11 percent of the federal credit, up from 4 percent. Filers with two dependent children could increase their EITC credit to 14 percent, up from 11 percent. Those changes amount to $53.1 million in tax cuts.

Eligibility for the Homestead Tax Credit (HTC) would be increased to $30,000 in household income in the second year of the biennium, and the credit would become indexed to inflation that year. Approximately 160,000 new filers would be eligible for the tax credit, while more than 100,000 current filers would receive larger credits, totaling $38.9 million in tax reductions. Only seniors, those with disabilities, and those on earned income may claim the HTC.

Individuals who qualify for the EITC or HTC are income-limited, so the majority of the funding for the credits comes from other taxpayers.

Evers’ budget would also change tax cuts already in law. During December’s Extraordinary Session, lawmakers passed across-the-board income tax rate reductions using funds from online sales tax collections, following a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision. The budget proposal officially requires the state to begin collecting those funds, raising $93.9 million in the biennium.

Thursday’s proposal would focus the income tax rate reductions passed in December solely on the bottom-most income tax bracket. Currently, the lowest tax rate is 4.0 percent for single earners making up to $11,230 and married-joint earners making up to $14,980. The change that lawmakers passed in December would split the reductions across tax brackets.

Wisconsin’s marginal tax rate system means that every taxpayer’s first earned dollars, up to the cutoff ($11,230 or $14,980), is taxed at the same rate. For that reason, everyone paying taxes in the state would benefit at least slightly from the measure. However, the Budget In Brief document does not state the proposed rate for this particular change.

One final note on taxes: apart from the minor shift on income taxes described above, Evers’ budget does not raise the general sales, corporate, or individual income tax rates. For all the tax increases tucked into other parts of the budget, the Governor stayed away from a Doyle-style ramping up of individual income tax rates. Consider us pleasantly surprised on this front.

Health Care

Evers’ budget accepts the federal Medicaid expansion under Obamacare while significantly increasing spending on a wide range of programs. The Medicaid expansion has been a costly proposition for states that accepted it. Medicaid spending in Ohio, for example, skyrocketed 35 percent in four years – from $18.9 billion to $25.7 billion between fiscal year 2013 and 2017. And in Minnesota, premiums increased 50-67 percent, forcing the state to implement a reinsurance program costing taxpayers at least $800 million so far. The federal dollars that follow a Medicaid expansion are anything but “free money,” as advocates persistently claim.

Despite these and many other stark cautionary tales, the Evers budget proposes expanding Medicaid eligibility to everyone earning between 0-138 percent of the federal poverty level. In 2019, that income level is $34,638 for a family of four, making 82,000 more people eligible for the program. However, with 92 percent of the population already insured—the vast majority of them through employer-based insurance — it’s likely a sizable share of those 82,000 newly eligible for government assistance already have insurance through their employers. That means many people who join the program would be moving backward, from self-sufficiency to dependence on government health care.

The budget asserts that expanding Medicaid will save $325 million in GPR across the biennium because of the federal government’s enhanced 90 percent match versus traditional Medicaid, a tenuous stream of dollars from a federal government already drowning in $22 trillion in debt. As with traditional Medicaid and its notoriously low reimbursement rates, the federal government is likely to back off that enhanced match in the future and leave state taxpayers holding the very expensive bag. Nonetheless, Evers’ budget proposal accepts and then immediately spends the $325 million—plus a lot more—on increased payments to health care providers and other new spending.

In all, the budget directs $580 million in additional dollars back to health care providers catering to Medicaid patients through the BadgerCare Plus program.

The budget spends $365 million more on reimbursement payments to hospitals serving Medicaid patients through five different, more traditional reimbursement avenues. That includes $142 million more in payments to hospitals handling a larger number of Medicaid patients than most; $100 million more for payments to acute care and critical access hospitals; $20 million more for payments to pediatric hospitals; and $1.2 million more for rural hospitals.

The proposal also hikes spending on considerably less-traditional “health” spending. It spends $45 million more for “non-medical services to reduce and prevent health disparities that result from economic and social determinants of health” such as “housing referral services, stress management, nutritional counseling, transportation coordination, etc.” It’s a significant expansion of the left’s beloved cradle-to-grave set of government programs, paid for using $45 million of precious tax dollars meant for actual health care.

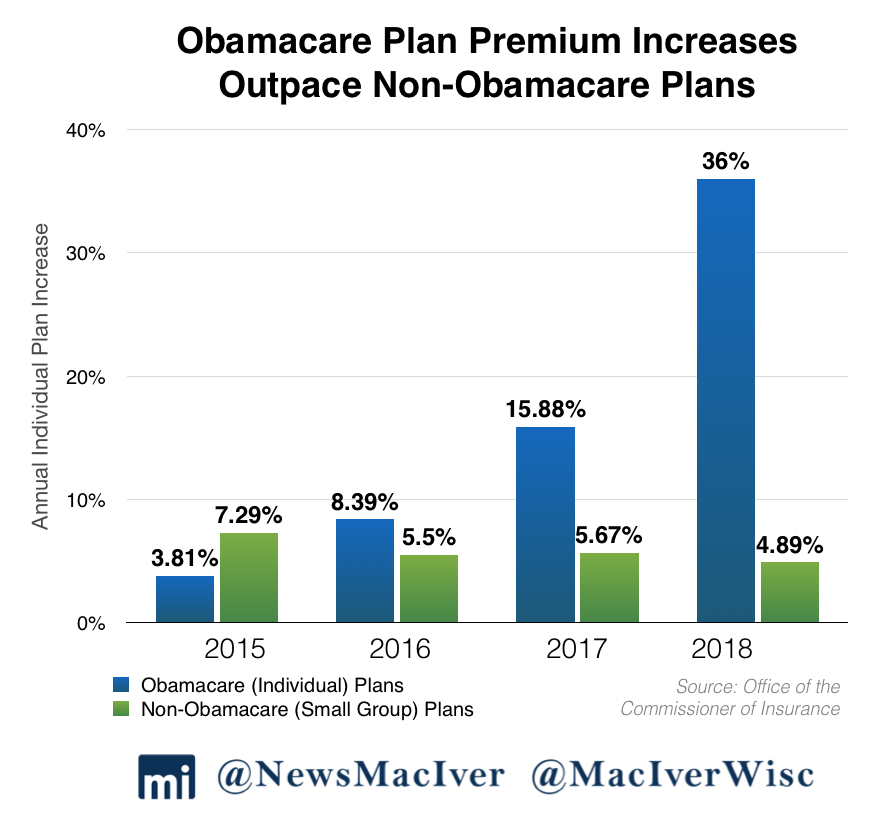

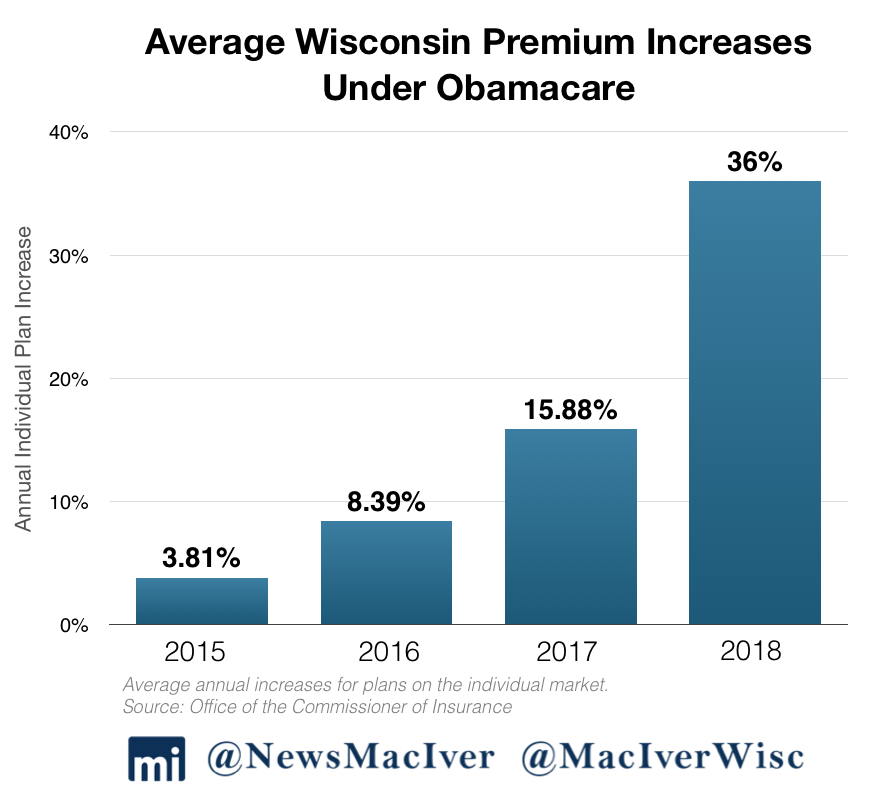

The budget builds off Gov. Walker’s reinsurance program, aimed at holding down premiums on the individual health insurance market in the era of Obamacare’s skyrocketing premiums. The continuation of this Walker-era program is a not-so-subtle admission that Obamacare has failed spectacularly to “bend the cost curve down,” and that failure is costing Wisconsin taxpayers dearly. The budget buttresses the program with $200 million in all funds spending for the Office of the Commissioner of Insurance in the second year of the budget. While the Walker administration, when he rolled out the plan, said it would cost taxpayers $34 million out of state coffers, Evers’ plan hikes the OCI budget by more than $72 million in the second year of the budget in state spending, or GPR — and by more than $200 million in all funds in the budget’s second year — to “fully fund” the program.

[bctt tweet=”#wibudget: Overall spending is significantly higher, especially with federal Medicaid dollars in the mix. In 2020, all funds DHS spending jumps more than $1 billion (an 8.5% increase), and more than half a billion dollars more in 2021.” username=”MacIverWisc”]

The spending plan includes an effort to lower prescription drug prices, in large part through government mandates. It proposes requiring drug companies to justify price increases, disclose proprietary information like production and marketing costs, and requires the OCI to post the information in the name of transparency. It also requires pharmacy benefit managers to register with the state and “disclose price concessions they receive from drug companies” and calls for importing generic drugs from abroad to Wisconsin.

The budget makes an effort to expand access to dental care, an area in which Wisconsin lags the nation. It spends a lot of money to do so—$43 million. The plan implements a dental therapy license in Wisconsin to increase the dental professional workforce, a market-driven option MacIver summarized in a policy brief last year, but Evers’ proposal also comes along with a hefty price tag. It spends $1.5 million to subsidize educational institutions that add a dental therapy program, with the goal to “put Wisconsin on the cutting edge of this emerging career field…” In addition to expanding spending to the tune of tens of millions of dollars for dental care under BadgerCare Plus and Medicaid, the budget also increases spending on a series of programs aimed at in-need populations and at grants for dentists who practice in rural areas or provide care to the disabled.

A series of critical Medicaid reforms enacted under Gov. Walker are also repealed wholesale by Evers’ budget, despite protections enacted during December’s extraordinary session. Work requirements and health risk assessments for childless adults seeking Medicaid are struck. Walker increased from 20 to 30 hours a week the time that able-bodied adults (ages 19 to 49) without children must be working, training for work, or looking for work to receive BadgerCare health insurance. That’s the federal maximum, as even Democrats in Congress recognize that 30 hours is not too much to ask for. Evers’ budget rolls that back.

Nominal premiums of $8 for households earning from 51-100 percent of the federal poverty level are struck; requirements that recipients be in compliance with child support orders are struck; copays for non-emergency medical services are struck; and Medicaid Health Savings Accounts are eliminated entirely.

In addition, the proposal includes a variety of provisions aimed at behavioral and mental health care and substance abuse treatment; it spends $69 million more for reimbursement rate increases for Medicaid recipients seeking mental and behavioral health care.

In all, the budget proposes to increase the Department of Health Services’ (DHS) budget by $36.7 million in 2020 and $255.7 million in 2021, GPR. The Office of the Commissioner of Insurance (OCI), charged with implementing the reinsurance program, is held steady in 2020, but receives a $72.3 million GPR bump in 2021.

Overall spending is significantly higher, especially with federal Medicaid dollars in the mix. In 2020, all funds DHS spending jumps more than $1 billion (an 8.5 percent increase), and more than half a billion dollars more in 2021. The all funds OCI budget jumps $200 million in 2021 to keep the Walker reinsurance program in place.

The Long-Anticipated Gas Tax Increase

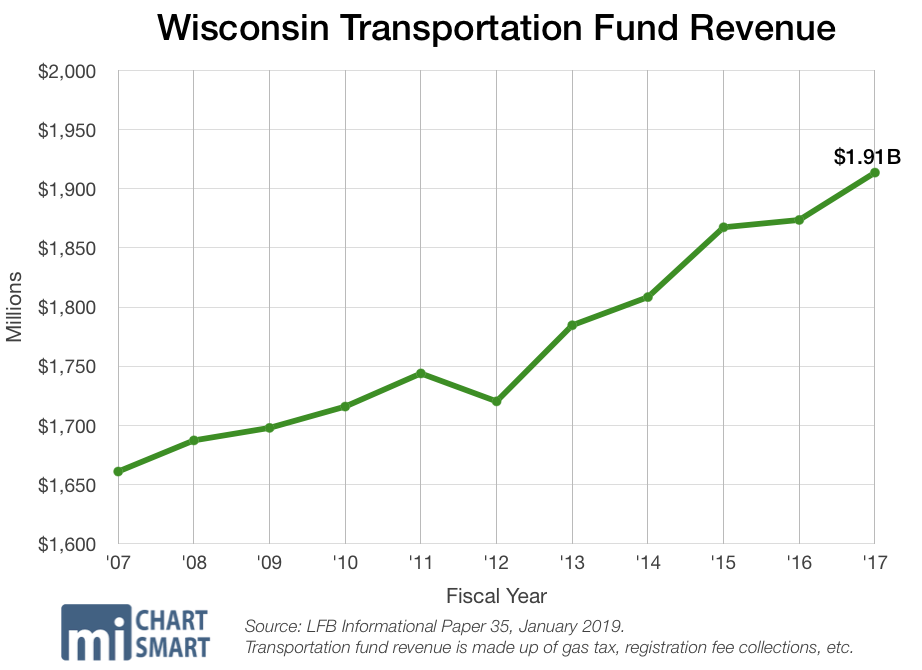

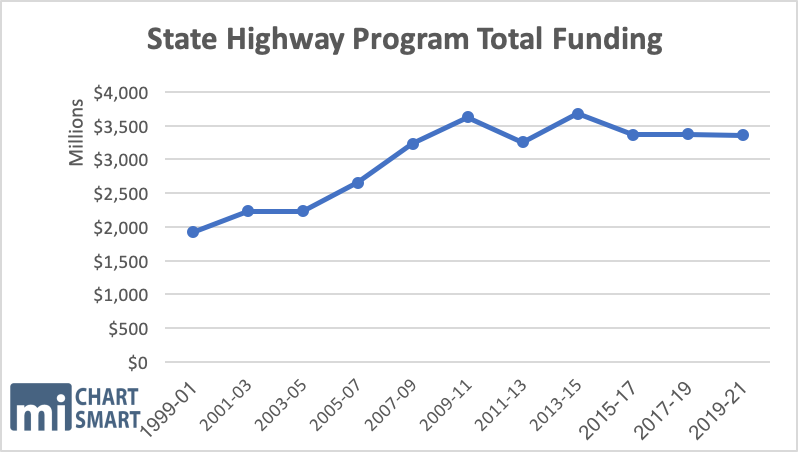

The Department of Transportation gets a $627 million boost in the governor’s budget, bringing the total up to $6.63 billion from last budget’s $6 billion.

That increase will be funded with an eight cent gas tax up front, raising $264 million, plus another one cent increase as a result of indexing starting in April 2020. Many lawmakers like indexing because it’s an automatic tax; it increases transportation tax revenue without forcing legislators to actually cast a vote on the hike. In essence, taxation without representation. Evers also wants to increase vehicle registration fees by $10, heavy truck fees by 27 percent, and create a new hybrid vehicle fee. He claims these increases will be offset by eliminating the minimum markup on fuel. The minimum markup law is a Depression-era relic that sets a price floor on numerous products, including prescription drugs and gasoline. The minimum markup on products other than gas is maintained in Evers’ proposal.

The budget proposal would cut funding to major highway projects by $5.5 million, and to the highway “mega projects” category by $203.7 million. Most of Evers’ attention in the state highway program goes to the state highway rehabilitation program, which he increases by $225.7 million over the 2017-19 budget.

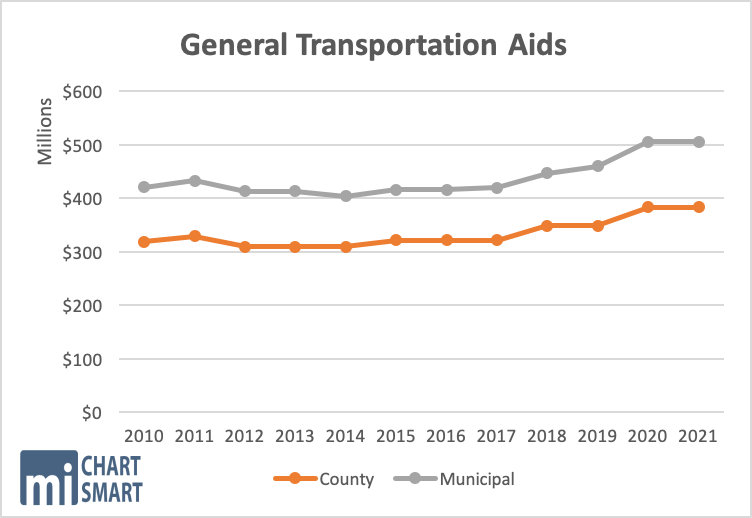

His main priority with road funding is on increasing road aids to local governments. Most local transportation aid comes in the form of general transportation aids (GTA) and is disbursed according to the calendar year as opposed to the fiscal year, which runs July to June. This year, the state will distribute $348,639,300 to municipal governments and $111,093,800 to county governments. Evers wants to boost that by 10 percent. That comes out to $383,503,200 for municipalities and $122,203,200 for counties next year. He also wants to increase the mileage aid to $2,628 per mile.

The transportation budget includes $338 million in additional bonding authority for transportation over the current budget.

Evers’ budget would do away with the “Fed-Swap” law, which requires DOT to consolidate federal funding into as few major highway projects as possible. The axed reform saves money by limiting the number of projects subject to the more stringent and costly federal requirements, including prevailing wage.

The budget would allow the DOT and DNR to use eminent domain to build bike paths and sidewalks.

The End of the Property Tax Freeze

In addition to all the ways Evers’ budget would raise taxes at the state level, his plan would also allow local governments to increase property taxes in several different ways. When combined into individual tax bills, property owners could be in for a real shock next year.

First, Evers would eliminate the school levy tax credit and the first dollar tax credit. Those credits would provide about $2 billion in property tax relief over the next two years without the change. School districts would also be able to hold referendums whenever they want, doing away with several important controls on property taxes at the state level.

[bctt tweet=”#wibudget: Evers’ plan would also allow local governments to increase property taxes in several different ways. When combined together into individual tax bills, property owners could be in for a real shock next year.” username=”MacIverWisc”]

Next, Evers would adjust revenue caps for municipalities, counties, and tech school districts. Currently, they can only increase their levy by their percentage of net new construction from the previous year. The budget proposal would set a minimum increase of 2 percent. Most communities currently have less than 1 percent growth each year, and the state average for 2018 was 1.62 percent. As a result of this change, 85 percent of Wisconsin communities would see the municipal, county and tech college portions of their property tax bills grow at a faster rate year after year than they do now.

On top of all that, local governments could exceed those higher caps to fund emergency dispatch centers and establish mass transit routes to neighboring communities.

The plan would also increase property taxes on big businesses, by allowing municipalities to base property taxes on the basis of that business’ total income rather than the value of a given property. Individuals who own homes aren’t charged property taxes based on their income — they’re charged based on the value of their home or land. This shift would fundamentally change how property taxation is calculated in Wisconsin.

Finally, local governments would be allowed to raise fees without having to lower their tax levies in exchange. This means local governments could start charging residents for things like garbage pickup and recycling without having to lower property taxes. In other words, if you’re not paying for things like garbage pickup right now, chances are you will be.

Big Labor

Evers’ first budget handsomely rewards his Big Labor allies, and is a full-on assault on worker freedom.

“The budget reverses many changes made over the past eight years that have weakened the state’s tradition of championing workers, collective bargaining and local control,” the budget documents states.

What Evers plans to do is bring back forced union dues, reinstate artificial wage floors that cost taxpayers big, and force the return of union exclusivity contracts.

The budget restores the prevailing wage law for state and local public works projects. Evers asserts bringing back the Great Depression-era relic “ensures that workers are not underpaid relative to other workers performing similar in the area.”

[bctt tweet=”#wibudget: What Evers plans to do is bring back forced union dues, reinstate artificial wage floors that cost taxpayers big, and force the return of union exclusivity contracts.” username=”MacIverWisc”]

Wisconsin’s previous prevailing wage statute, which tied wages on taxpayer-funded construction projects to inflated rates paid by unions, was repealed for local projects in the 2015-17 state budget in a compromise. Walker subsequently signed legislation that repealed the union-led, artificial wages for state projects. The changes allow markets to set wage rates for local construction projects, saving taxpayers from well-documented cost overruns.

Evers’ budget also would eliminate what the document describes as Wisconsin “so-called” right-to-work law. It’s called right-to-work precisely because it prohibits private-sector labor organizations from making compulsory union dues a condition of employment. In 2015, Wisconsin became the 25th right-to-work state in the nation when Walker signed the worker freedom legislation into law. Big Labor immediately challenged the law in court, and lost. With Evers, organized labor is found, and their vendetta against right-to-work is now being carried out by the Democratic governor.

In more payback for unions, Evers is pouncing on another Walker-era victory. His budget plan permits the project labor agreements for public works projects that the former governor signed out of existence in 2017.

PLAs stipulate that only union firms can bid on a project, and many units of government required them — shutting out non-union shops.

The Republican-led reform law prohibits a government from requiring a PLA as a condition to bid on a taxpayer-funded project — a big win for the free market and the taxpayers who benefit from increased competition. Democrats have argued the law is yet another attack on unions and that it limits local control.

Curiously, no mention of Walker’s signature reform, Act 10, is made in the Budget In Brief document. Despite continuous attacks on the campaign trail and earlier, Evers’ document does not appear to make changes to reforms such as increased benefits contributions for public employees, or union recertification votes. However, it’s possible that such changes are included in the document’s legal language but not the brief. Still, for a governor who campaigned on championing collective bargaining and undoing years of conservative reforms, one would think changes to Act 10 would be front and center.

The governor’s budget plan also gets rid of a reform law aimed that ends the patchwork of employment laws statewide. Evers’ provision would repeal preemption of costly local government ordinances on family and medical leave, wage claims, employee benefits, hours of work and overtime, and solicitation of prospective employees’ salary histories. The preemption reforms require such employment regulations to be governed by uniform statewide policy, not created through the whims of local governments, at business and taxpayer expense.

K-12 Education

Property tax levels are largely driven by spending in schools — another issue area where this proposal would spend vastly more.

Evers’ budget proposal for K-12 education largely mirrors the budget request submitted last fall by the Department of Public Instruction (DPI), when he was the head of that agency. The total changes would increase DPI spending by nearly $1.6 billion over the biennium, more than the DPI budget request. It’s also more than twice the dollar amount of the last budget’s increase to K-12 education. That bill upped spending by more than $630 million in the biennium, the highest dollar amount in history at the time.

The majority of K-12 dollars flow through equalization aid, also known as general aid, which exists to even out funding disparities in local property taxes. Property-poor districts such as Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) receive disproportionately high amounts of equalization aid. Forms of aid like the school levy tax credit and the first dollar credit are considered categorical aid, and are distributed equally across school districts.

Under Evers’ plan, the school finance formula would significantly change, and billions more dollars would flow through equalization aid. The school levy tax credit and first dollar credit would be eliminated in the first year, with that funding instead moving to general aid. That move alone is likely to increase property taxes, since money that is now used to offset local property taxes will instead flow directly to schools. The plan includes a hold harmless provision so that no district will receive less in state funding than current law.

[bctt tweet=”#wibudget: The total changes would increase DPI spending by nearly $1.6 billion over the biennium, more than the DPI budget request, and more than twice the dollar amount of the last budget’s increase to K-12 education.” username=”MacIverWisc”]

Limits on school district referenda implemented in recent years would be done away with. School districts would no longer be limited in the number of referenda they may hold in a calendar year, another measure certain to increase property taxes across the state.

Other changes to K-12 funding include an increase in the revenue limit adjustment by $200 in the first year and $204 in the second year, with future increases indexed to inflation. The plan also increases the low revenue adjustment from $9,100 under current law to $9,700 in 2020 and $10,000 in 2021. That’ll allow school districts across the state to levy millions more in local property taxes. Assembly Republicans have pushed to increase the low revenue adjustment in recent years, including during the previous budget debate. The Assembly Republican plan in 2017-19 would have increased the low revenue adjustment by much less than Evers’ plan, and would have allowed local property taxes to increase by up to $92.7 million statewide. Evers’ plan, of course, goes much further than that, signaling even bigger property tax increases down the road.

The budget would also spend more than $600 million on students with special needs, while also limiting many of those students’ options. The majority of the hike would go toward increasing the state reimbursement level for special education costs by $606 million over the biennium. The high-cost special education program would be made sum sufficient, and special education transition readiness grants would increase from $1,000 per pupil to $1,500 per pupil, increasing spending by more than $7 million on those grants.

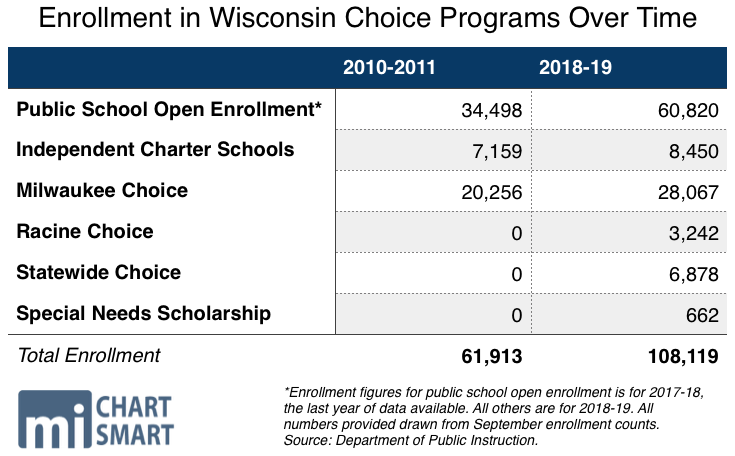

While students with special needs who attend public schools are rewarded in the proposal, students in the Special Needs Scholarship Program (SNSP) would be shut out of their educational options. That program, established in the 2015-17 budget, allows students with special needs to attend private schools with scholarships from the state. No new students could join the program after the 2019-20 school year.

Currently, 662 students participate in the program, more than triple the enrollment just two years ago when the SNSP first began. A 2019 audit by the nonpartisan Legislative Audit Bureau (LAB) showed that parents reported strong satisfaction with the program, including improved behavior from their children and more positive relationships with peers compared to their experiences in public schools. In the audit, one respondent is quoted, saying that SNSP “has made it financially possible for my child to receive the appropriate, individualized education to which he was entitled but not receiving in his public schools.”

Other rollbacks to educational choice include freezing enrollment in the popular private school choice programs in Milwaukee, Racine, and statewide. Total seats available would freeze after the next school year. Students could join the programs when others graduate or otherwise leave. An estimated 38,187 students across the state participate in the three programs, with nearly three-quarters in Milwaukee.

The programs exist to allow impoverished students go to the schools of their choice using vouchers from the state. Students earn higher ACT and Forward Exam scores than their public school peers, and families report higher levels of satisfaction compared to public school. The vouchers are worth less than average aid to public schools. Another budget provision would require individual property tax bills to include the total figure spent on vouchers.

The Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (MPCP) is the country’s oldest voucher program, and the student enrollment cap was lifted in 2011. Since then, participation has steadily grown, making it the largest choice program in the state. Nearly 29,000 students are enrolled in the MPCP today.

The number of independent charter schools would freeze under the proposal, with a ban on authorizations of new schools by entities other than public school districts until 2023. Under current law, any chancellors of the UW System, the City of Milwaukee’s common council, tribal authorities, any technical college district board, the Waukesha County Executive, and the UW-System Office of Educational Opportunity can authorize independent charter schools.

Already-existing charter schools would be allowed to continue operating and adding new students. In the current school year, 8,450 students attend independent charter schools.

The best-rated school at MPS is a charter school, though it was authorized by MPS itself. Milwaukee Excellence received 94.3 out of 100 points on the 2018 report cards, with math proficiency double that of the district average.

Choice and charter programs have been remarkably successful in Wisconsin, showing strong proficiency rates despite higher levels of student poverty. Of the 17 MPS schools receiving five stars on the most recent state report cards, 10 are in the private choice program, four others are charter schools, and just three are traditional public schools. On the other end of the scale, 50 MPS schools received one star in 2018, or “failing to meet expectations” designations. Ten of those schools are in the private choice program, while three are charters and 37 are traditional public schools.

[bctt tweet=”#wibudget: According to the budget, students currently participating in choice programs would not be affected by proposed changes. However, the ban on adding new seats or students will almost certainly lead to school closures.” username=”MacIverWisc”]

According to the budget document, students currently participating in choice programs would not be affected by proposed changes. However, the ban on adding new seats or students will almost certainly lead to school closures.

Public school open enrollment, the state’s most popular form of school choice, is not targeted by the budget proposal. That long-standing program allows students to move to other public schools if they so choose.

Other changes to public school finance include a number of grant increases for target areas. Student mental health needs would be funded by more than $63 million for in-school pupil services, staff training, and other related initiatives. A new Urban Excellence Initiative would spend more than $15 million on closing achievement gaps in the state’s five largest public school districts. Teachers would be required to have 45 minutes or a single class period in planning time every day, whichever is greater.

The budget proposal includes myriad of other, comparatively smaller initiatives that nevertheless total millions of dollars in spending, including the recommendations of the Blue Ribbon Commission on School Funding. A future MacIver analysis will examine this budget proposal’s K-12 education spending in closer detail.

University of Wisconsin System

Evers’ budget proposal for the UW System would continue the popular tuition freeze for in-state undergraduate students. The UW System would see a boost in funding to the tune of $175 million over the biennium.

Spending increases at the UW System include $10 million for fellowships and loan forgiveness for certain nursing candidates who commit to teaching in the system for three years after graduating. Student support services for the UW Colleges would see $5 million, and 20 more employees would be hired for UW-Extension county-based representatives. Need-based grants for Wisconsin students attending the UW System, tech colleges, private universities or tribal colleges would be funded by $17.3 million in GPR.

The proposal sets up a study committee to examine creating a state-run student loan refinancing authority. The committee is charged with making recommendations by late 2020, for inclusion in the 2021-23 state budget.

Students who are citizens of other countries but who graduated from a Wisconsin high school, lived in Wisconsin for three continuous years before high school, or have applied for a permanent resident visa would qualify for in-state tuition.

All told, Evers’ budget spends $5.9 million more than the UW System requested in last fall’s agency budget request, and creates 219.84 new full time positions.

The Wisconsin Technical College System would also receive a funding increase of 7 percent in each year, totaling $18 million over the biennium.

The budget proposal eliminates the Early College Credit Program, which allows high school students to take university classes under a cost-sharing agreement. Students can earn high school credit, college credit, or sometimes both. Instead, the budget requires that the UW System implement a program to provide tuition-free classes for high school students. The budget gives similar treatment to a program that lets high school students take classes at tech colleges, instead requiring the tech colleges to provide them for free.

Welfare and Other Government Reforms

The budget rolls back some of Walker’s reforms to the state’s welfare systems. Able-bodied adults with dependents aged six to 18 would no longer need to satisfy work requirements in order to receive FoodShare. Drug testing for most public assistance programs is eliminated.

However, in a nod to the success of the Walker administration’s changes, childless able-bodied adults would still be required to satisfy job requirements in order to get FoodShare. That became compulsory in April 2015.

Evers’ budget includes $5.3 million to help welfare recipients in the Wisconsin Works (W-2) program “access affordable Internet.”

“On behalf of these families, the Department of Children and Families will work with W-2 agencies to reimburse the appropriate Internet service providers on a monthly basis,” the budget document states.

It’s another big-government initiative, that looks a lot like the city of Madison’s failed broadband-for-all pilot program for low-income neighborhoods. Evers’ $5.3 million seems all the more excessive given that free Internet access is as close as the local library, neighborhood school, or any number of retailers and restaurants.

Minimum wage for state employees would increase to $15 per hour in 2021. For everyone else, the state minimum wage would increase to $8.25 in 2020, followed by 75-cent increases annually until 2023. Once the minimum hourly wage reaches $10.50 in 2023, it would become indexed to inflation. The governor’s budget proposal also creates a task force to study how to get the state to a $15 per hour minimum wage.

Most state employees would see a wage increase of 2 percent in each year of the biennium, totaling $82.1 million in GPR. Another $12.1 million would be provided for targeted increases to certain state employees.

Wisconsin would make a statutory goal for all electricity produced in the state to be completely carbon-free by 2050. That’s pulled right out of the Green New Deal, which argues that the entire world should become carbon-free by 2050. As temperatures dipped below freezing in much of the state this weekend, a similar move enacted today would mean death by frost. Thirty years changes a lot, but it seems likely that Wisconsin will still be a cold northern state by 2050.

Other changes would limit the changes in law the Legislature passed during December’s Extraordinary Session, including the ability of the Attorney General settle cases without the approval of the Legislature. The Legislature would no longer be able to intervene in lawsuits as a matter of right.

Vast criminal justice and health-related reforms would decriminalize medical marijuana, while legalizing small amounts of recreational marijuana and expunging drug offenses under a certain amount. Seventeen-year-old offenders would also be moved from the adult justice system to the juvenile justice system. That includes violent and repeat offenders, a proposal much more expansive than other ideas floated in the past.

The MacIver Institute released a report in 2016 studying the fiscal effects and feasibility of returning only non-violent, first time 17-year-old offenders to the juvenile system. Since young people are less likely to reoffend and return to prison if originally processed through the juvenile system, the state is likely to see savings in reduced recidivism. The Governor’s plan would also give $5 million to counties, who oversee the juvenile system.

The state would vastly expand its spending on broadband grant programs, spending $78.6 million in the biennium through the Public Service Commission. It would create a new statutory goal for minimum broadband speed across the state, and spends $5.3 million on internet access for welfare recipients.

The budget plan strips a number of key government reforms codified in state law by Walker and the Republican-led Legislature.

The Governor restores administrative language that gives deference to state bureaucrats’ interpretations of law. Republican reforms prohibited the practice of state courts simply accepting agency conclusions of the law. So did the state Supreme Court, which recently affirmed so in northern Wisconsin property rights case.

“We have ended our practice of deferring to administrative agencies’ conclusions of the law,” Justice Rebecca Dallet wrote for the majority in cementing the court’s position change first declared in a decision last June. Interpreting the law, under Wisconsin’s constitution, is the judicial branch’s domain, not the executive branch’s.

And Evers rolls back legislative reforms on agency use of so-called guidance documents used by bureaucrats to set policies. Critics of the practice say agencies use the documents to bypass legislative oversight and review. The same problems occurred during the Obama administration, when agencies stopped creating rules and instead issued “guidance.”

Evers’ office will soon introduce a capital budget bill that will include recommendations for spending and borrowing for state buildings. The Budget In Brief also commits to at least $75 million in bonding in the capital budget for energy conservation programs.

All told, the budget document sets forth a wildly different view of government compared to the administration of the last eight years. The proposal creates many new government offices, programs, and credits, while increasing taxes on certain earners and hiking state borrowing by $448 million. It would eliminate hallmark reforms such as the right-to-work, bring back the state prevailing wage, and accept federal Medicaid dollars for expansion.

Since its release, Republican lawmakers have largely rebuffed the document, calling it a “liberal wish list.” The real work will begin when LFB releases its nonpartisan analysis later this month. Afterward, agencies will appear before the Joint Finance Committee to discuss their budgets and allow JFC to learn more. Then, finance will parse through the massive spending document, agency by agency, before it passes onto the full Legislature.

Evers has already indicated that he would be open to vetoing the entire budget if Republicans strip out too many of his reforms.

Taxpayers, hold onto your hats. It’s about to be a bumpy spring and summer. As always, MacIver will be here every step of the way. Look forward to more detailed analyses of individual budget sections in the days and weeks to come.