[bctt tweet=”As the budget committee prepares to vote on K-12 funding, MacIver reminds you how detrimental @GovEvers’ plan would have been in our latest analysis. #wiedu #wiright #wipolitics” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”The K-12 spending increase that Finance Republicans will pass becomes their negotiating position with @GovEvers. How high over current spending will they go? #wiedu #wiright #wipolitics” username=”MacIverWisc”]

May 22, 2019

By Ola Lisowski

Gov. Tony Evers – once educator, then bureaucrat, and now Wisconsin’s governor – has dedicated his life to public education. His gubernatorial campaign largely centered on the question of equity and progress in K-12 education. Yet his 2019-21 budget proposal, up for a Thursday vote in the state’s Joint Finance Committee (JFC), would have turned back the clock on the very values he claims to hold dear.

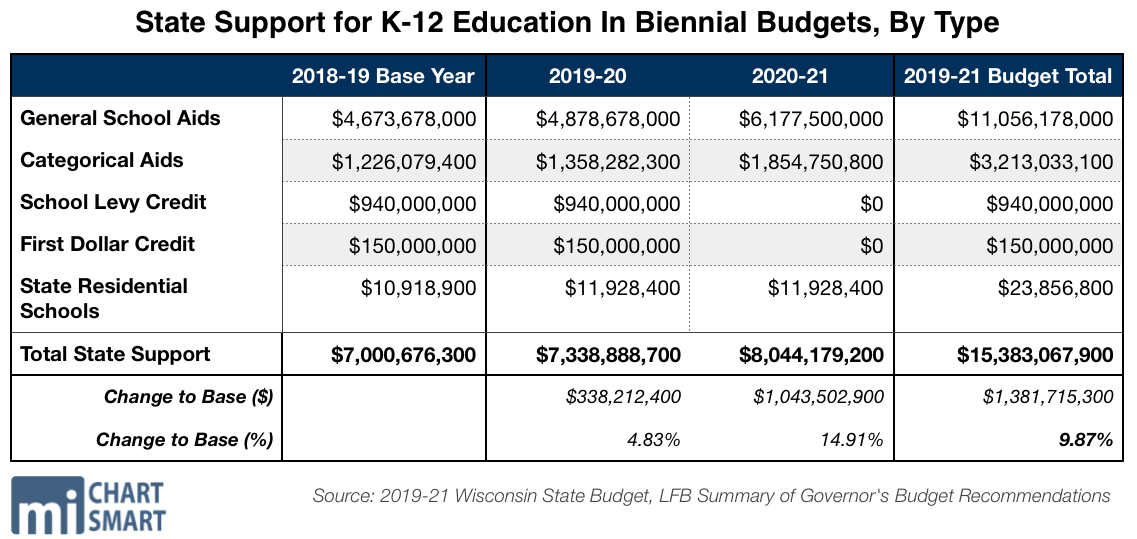

What Evers Proposed on Choice

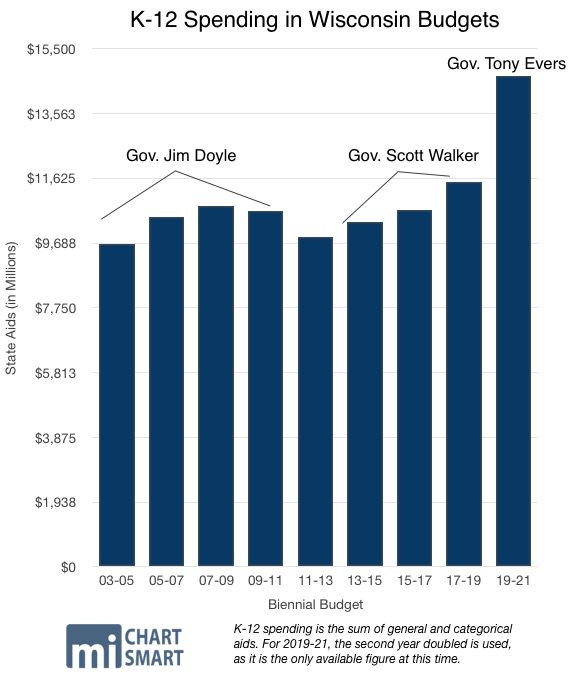

As proposed, Evers’ budget would have added $1.6 billion over current funding to the Department of Public Instruction (DPI), the department he led until January. DPI would receive more than $15.83 billion over the biennium. That’s on top of the record-high increases in the last budget, which added over $630 million more.

While many conservatives and moderates balked at the sheer sum of money in question, the governor’s numerous attacks on school choice access were of particular concern.

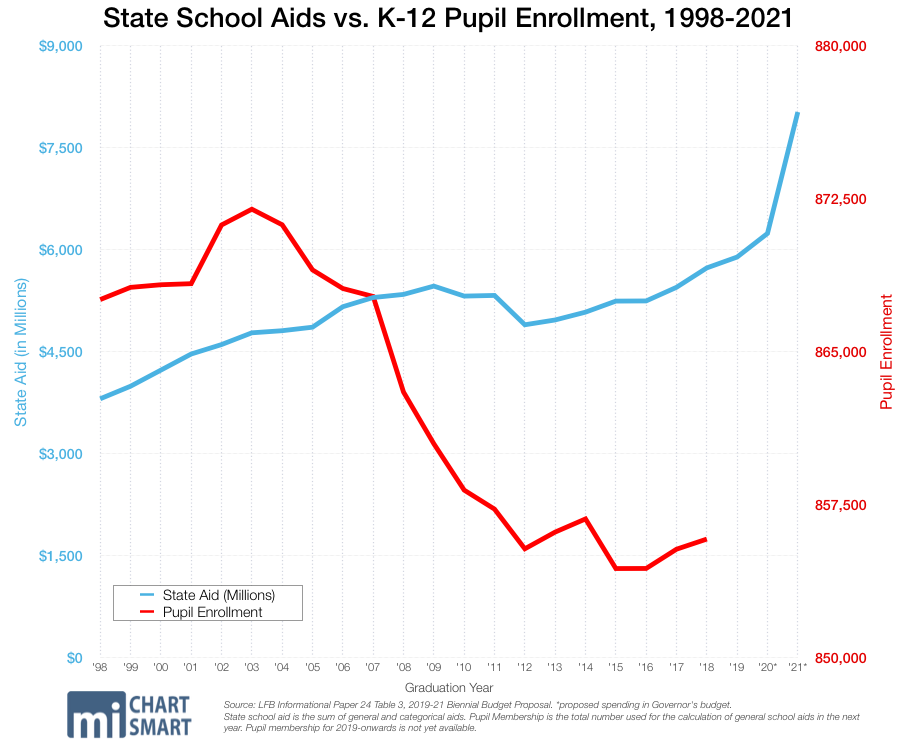

In the current school year more than 853,000 children attend Wisconsin public schools, a figure that has fallen for years. At the same time, K-12 investments have grown. The state continues to spend more money to educate fewer children.

Thanks to JFC, all of Evers’ proposals on school choice have already been stripped out of the budget document. Many of his changes to the school finance formula, like the elimination of property tax credits, are also gone. The powerful budget-writing committee will vote on what’s left for DPI on Thursday.

Still, it’s crucial to remember where we started this process, and what an unaltered Evers budget would have looked like.

Evers’ proposal would have frozen enrollment in the state’s popular school choice programs – the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (MPCP), the Racine Parental Choice Program (RPCP), and the statewide Wisconsin Parental Choice Program (WPCP).

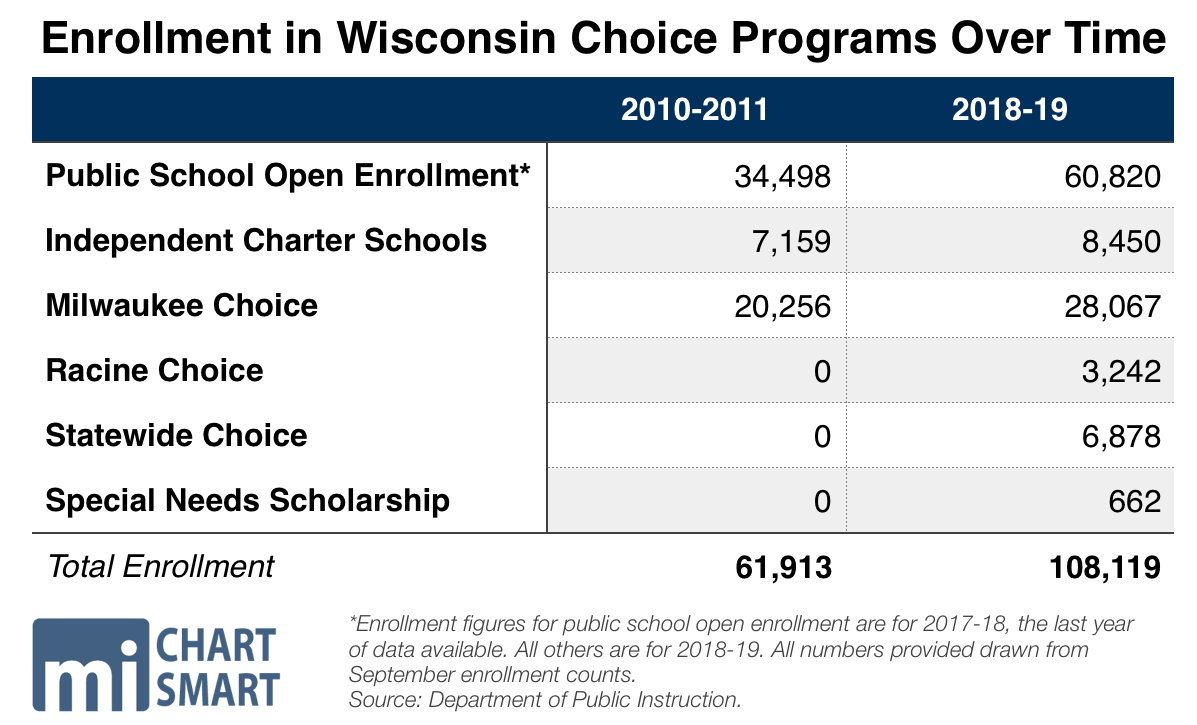

Today, more than 38,000 students are enrolled in private schools thanks to those three programs, an 89 percent increase from the 2010-11 school year. Students can only participate in the parental choice programs if their family incomes are below certain limits. In Milwaukee and Racine, families can earn up to 300 percent of the federal poverty level to qualify. For a family of four, that amounts to $75,300 for the 2019-20 school year. Outside of those two cities, the limit is 220 percent of the poverty level, or $55,220 for a family of four.

If families exceed the cap, their options are to either attend public schools or pay out-of-pocket for a private school education. Wealthy families already have the power to choose educational options for themselves. Until school choice, poor families didn’t. Evers would have turned back the clock on educational access for the most disadvantaged among us.

The programs aren’t just popular. They’re successful, too. Mountains of research nationwide have shown the academic, social, and fiscal benefits of school choice programs, including a robust study published Monday by the Cato Institute and Reason Foundation.

That study examined cost-effectiveness of private schools in the choice programs, and independent charter schools, compared to traditional public schools in the 2017-18 school year. Private and independent charter schools tend to be more cost-effective than district-run public schools in the state overall and in the majority of cities. In layman’s terms – the programs do more with less. In Milwaukee, private schools are 50 percent more cost-effective. Racine’s private schools are 75 percent more cost-effective.

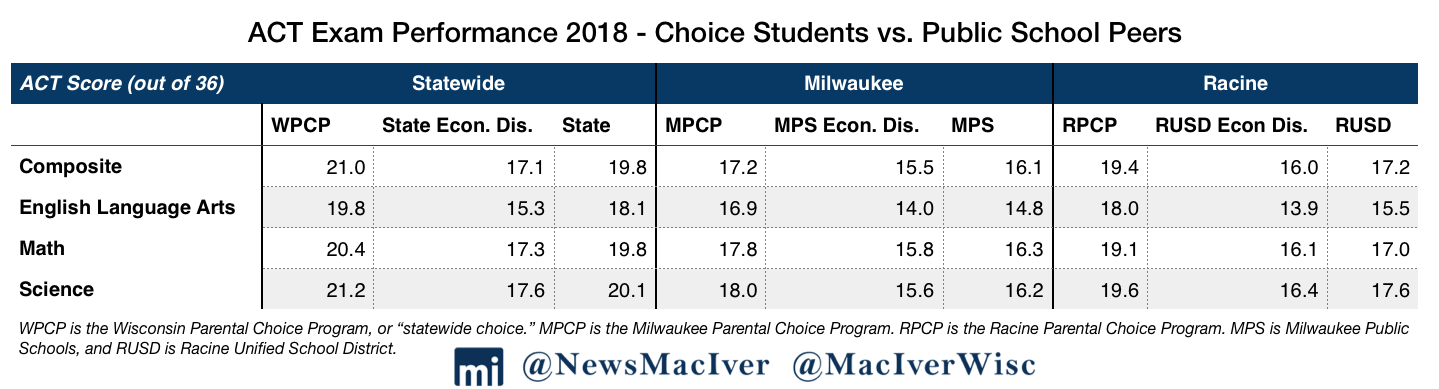

Raw test scores show the powerful academic impact of school choice as well. Participating students consistently post better academic outcomes than their public school peers, including on the most recent ACT Exams in 2018. The most recent DPI report cards also show this impact. Of the 17 schools at Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) that received five stars on 2018 report cards, 10 are private choice and four are charters. Just three traditional public schools at MPS received five stars in 2018.

While the governor flipped back and forth on how he’d treat vouchers while on the campaign trail, he came out swinging with his budget document. He claimed that freezing enrollment wouldn’t affect current students, but ignored the impact on their younger siblings and the fact that school doors would almost certainly shutter had his idea become law.

It’s also important to note what Evers wouldn’t have changed. His budget made no similar changes to public school open enrollment, the state’s largest form of school choice. That program, utilized by nearly 61,000 young people, lets students attend public schools outside of their own districts. You rarely hear complaints about open enrollment from the very vocal opposition to choice and charter. That’s because their many complaints are about politics, not policy.

A separate portion of Evers’ budget proposal would add more than $600 million for special education initiatives. No doubt, the most vulnerable of our population need extra help, and that’s certainly true in the classroom.

Evers would have closed the door on tens of thousands of economically disadvantaged children who have left public schools in pursuit of better options.

But Evers also would have ended the Special Needs Scholarship Program (SNSP) after the current school year, with no new students allowed to participate beginning in 2020-21. That program lets students with special needs attend the private school of their choice with a scholarship from the state. While Evers would have opened the door for more children in the public schools, he would have shut that door on students who already know the system doesn’t work for them at all. That’s a shame, and it’s far from the equity he so often speaks about.

His budget also would have barred independent charter schools authorizers from starting new charter schools until 2023. Those authorizers include any UW System chancellor, the city of Milwaukee’s common council, any tech college board, the Waukesha County executive, tribal authorities, and the UW System’s Office of Educational Opportunity. Under Evers’ proposal no new schools could be authorized by any body other than a school district until 2023.

He would have closed the door on tens of thousands of economically disadvantaged children who have left public schools in pursuit of a better option. Thanks to Republicans on JFC, none of these ideas are in the budget document anymore, though there will certainly be plenty of debate on them during Thursday’s executive session.

What Evers Proposed on the School Funding Formula

Evers has long pushed a rewrite of the state’s education finance mechanism. To be sure – it’s a broken, ineffective, overly complicated system. But his idea for fixing it would have stripped away crucial property tax controls, almost certainly ending the property tax freeze. Again, much of what he proposed was pulled out by JFC, but not all of it.

His original document would have eliminated the School Levy Tax Credit and the First Dollar Credit. Together, both credits total more than a billion dollars of property tax relief. Evers would have instead sent that funding through the equalization aid.

The majority of K-12 dollars flow through equalization aid, also known as general aid, which exists to even out funding disparities in local property taxes. Property-poor districts such as MPS receive disproportionately high amounts of equalization aid. Forms of aid like the school levy tax credit and the first dollar credit are considered categorical aid, and are distributed equally across school districts. JFC struck that change.

Other changes included an increase in the revenue limit adjustment by $200 in the first year and another $204 in the second year, with future increases indexed to inflation. The plan also increases the low revenue adjustment from $9,100 under current law to $9,700 in 2020 and $10,000 in 2021. That will allow school districts across the state to levy millions more in local property taxes. Both of those issues remain in the budget and will be huge points of debate on Thursday.

Another big aspect of Evers’ plan remains, though this one is more symbolic than anything else. Evers would restore the two-thirds funding promise, which commits the state to covering two-thirds of all school expenditures, with the rest covered by locals. That idea was originally put into law by Republican Tommy Thompson and stripped by Democrat Jim Doyle. In recent years, former Gov. Scott Walker slowly increased the state share of spending as the state’s fiscal picture improved. In the current budget year, 2018-19, the state covers 65.4 percent of school funding, a hair shy of two-thirds.

Republicans on JFC also maintained Evers’ proposals for poverty aid. Under that plan, Evers would have eliminated the $16.8 million high poverty aid program and reallocated the funding into the general school aid formula. Any economically disadvantaged pupil would be counted as 1.2 full time students instead of 1.0, building in more funding for any school with impoverished students.

Other changes to public school finance include a number of grant increases for target areas. Student mental health needs would be funded by more than $63 million for in-school pupil services, staff training, and other related initiatives. A new Urban Excellence Initiative would spend more than $15 million on closing achievement gaps in the state’s five largest public school districts. Rural schools would get more help, too, with a reworking of sparsity aid. Republicans are likely to act on all of those proposals.

The Plan that Doubled Down on a Lie

Apart from all of Evers’ proposals, much of the debate has been predicated on falsehoods, starting with the idea that public education was underfunded for years under Walker. They continue with the claim that school choice does not and has never shown positive results.

The data disagree with both points. As we’ve written before, Walker’s first budget cut agency funding across the board. Those cuts were made even bigger by the fact that his predecessor’s budget had been built on one-time federal stimulus funding.

But there’s also rarely a mention of the long-declining enrollment in public schools. In the current school year, more than 853,000 children attend Wisconsin public schools, a figure that has fallen for years. At the same time, K-12 investments have grown. The state continues to spend more money to educate fewer children.

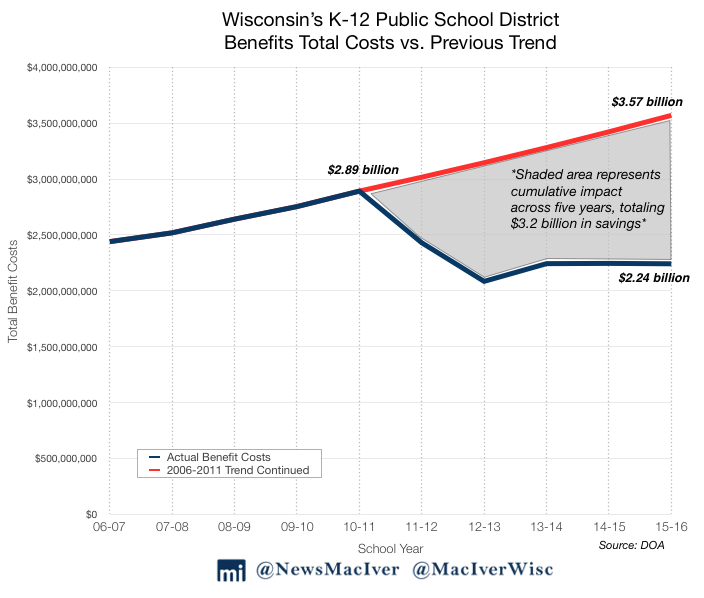

Prior to Act 10, benefits costs to districts had been increasing by 4.3 percent annually. Had that trend continued, taxpayers would be paying almost 60 percent more today.

And for all the claims Evers has made on what he believes to be the harmful effects of Walker’s Act 10, his budget does nothing to strip back those reforms. School districts have saved at least $3.2 billion on benefits plans since 2011 thanks to their newfound flexibilities. Even so, the majority of the taxpayer-funded plans are still incredibly generous, especially compared to the private sector.

Those savings are still reverberating. In March, Kenosha School District saved nearly $30 million on health care plans alone by switching providers. The district’s taxpayers will spend 41 percent less than their projections, and individual teachers will come out contributing even less toward their monthly premiums.

At 26 percent of districts, employees pay less than 12 percent toward monthly premiums on single plans. Years after Act 10’s requirement that public sector employees contribute at least 12 percent toward health care costs, just 74 percent of school districts comply with the rule for premiums. Prior to Act 10, benefits costs to districts had been increasing by 4.3 percent annually. Had that trend continued, taxpayers would be paying almost 60 percent more today.

That money adds up. In many cases, districts freed up dollars to go to the classroom by adjusting their benefits plans, Wauwatosa School District and MPS among them.

None of those savings are accounted for in state figures that show how much Walker put toward education. It is billions of dollars, previously locked down, that districts can now spend on their own priorities. Walker’s public sector collective bargaining reform legislation bent the cost curve for school and ultimately, for taxpayers. While spending on health care has exploded across the country, Wisconsin bucked the trend because of Act 10.

Why does this matter? Simply put, if school districts saved $3.2 billion on health care and retirement benefits, that money should have been directed to other education programs.

Finally, DPI’s own figures show just how little districts spend on those priorities. State figures show just 54 percent of district spending goes toward instruction. Just a slim majority of all K-12 education spending reaches the classroom.

If top-heavy overhead were reduced, the teachers doing the vast majority of meaningful work in schools could perhaps be better compensated. Instead, the many secondary and tertiary roles schools have taken on directly compete with the primary reason for schools’ existence: educating children.

Act 10 gave districts the tools to save money, and the flexibility to put it where it’s needed.

Still, a broken system will always demand more money. On Thursday, Democrats are likely to argue that Evers is simply attempting to fix eight years of Walker reforms. Republicans aren’t likely to go along with all $1.6 billion in new spending for schools, though they will certainly make new investments. But it’s important to remember where we were, and how far we’ve come.

Evers would turn the dial back – not only for taxpayers, but for the students who need help the most. School choice supporters can likely rest easy now that the worst of his budget is gone, but it’s a debate that is always worth revisiting.

As always, we’ll be there. Thursday’s executive session begins at 11 a.m. Follow @MacIverWisc and @NewsMacIver for live coverage, and stay tuned for more wrap-up coverage as the first major issue of the 2019-21 budget is finalized.