[bctt tweet=”As Joint Finance prepares for a big day Tuesday, tackling Medical Assistance, FoodShare and other related programs, we remind taxpayers what @GovEvers proposed in his original budget. #wibudget #wiright #wipolitics” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”As Joint Finance prepares for a big day Tuesday, tackling Medical Assistance, FoodShare and other related programs, we remind taxpayers what @GovEvers proposed in his original budget. #wibudget #wiright #wipolitics” username=”MacIverWisc”]

June 3, 2019

By Ola Lisowski & Chris Rochester

Wisconsin’s powerful budget-writing committee will be taking up agency budgets for the Department of Health Services (DHS) and Department of Children and Families (DCF) on Tuesday. Before the Joint Finance Committee (JFC) dives into specifics, it’s a good opportunity to remind taxpayers what exactly Gov. Tony Evers proposed in his 2019-21 budget for these crucial issue areas.

In short, Evers’ proposal seeks to encourage people to leave their private plans and seek increased dependence on a government program with poor health outcomes.

The cornerstone of Evers’ budget proposal is Medicaid expansion, an issue that was key to his gubernatorial campaign. However, in its first motion for the 2019-21 cycle, the Republican-led JFC pulled that provision out of the budget as a non-fiscal policy item. During Tuesday’s debate, expect the issue to be front and center, despite the fact that whatever omnibus motion Republicans pass will not include Medicaid expansion.

Health Care

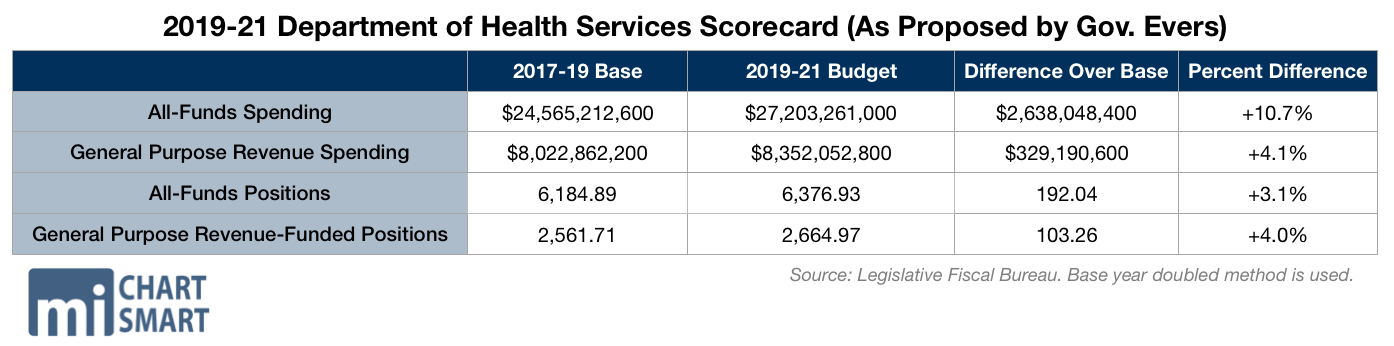

Evers’ proposed spending plan allocates $13.3 billion all-funds spending in 2020 and $13.9 billion all-funds in 2021 to DHS. The 2021 funding level is a $1.6 billion, or 8.5 percent increase, over the 2019 adjusted base budget in all-funds.

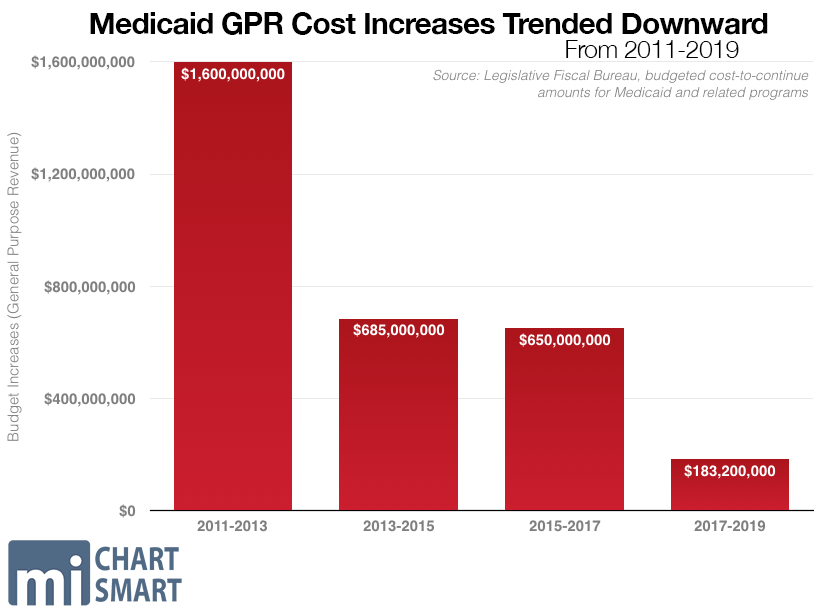

The massive increase is a sharp deviation from the trend during the administration of former Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican. The 2019 adjusted base spending for the second year of the governor’s final DHS budget is actually $293 million less than Walker’s recommendation, meaning spending came in lower than expected. While Walker’s budgets consistently increased spending on DHS—which administers the massive Medical Assistance program, including Medicaid—the size of the spending increases had been going down budget after budget.

From state coffers, or general purpose revenue (GPR), the Evers budget proposes spending just over $4 billion GPR on DHS in 2020, a 0.9 percent hike; but it spends $4.3 billion in 2021, a 6.3 percent increase.

In total, over two years, Evers’ budget spends $27.2 billion all-funds, and $8.4 billion in GPR, on DHS. That’s an 11.5 percent increase over the $24.4 billion all funds, and a 6.3 percent increase over the $7.9 billion GPR, allocated in the last budget. It also adds 192.04 full-time equivalent positions over two years.

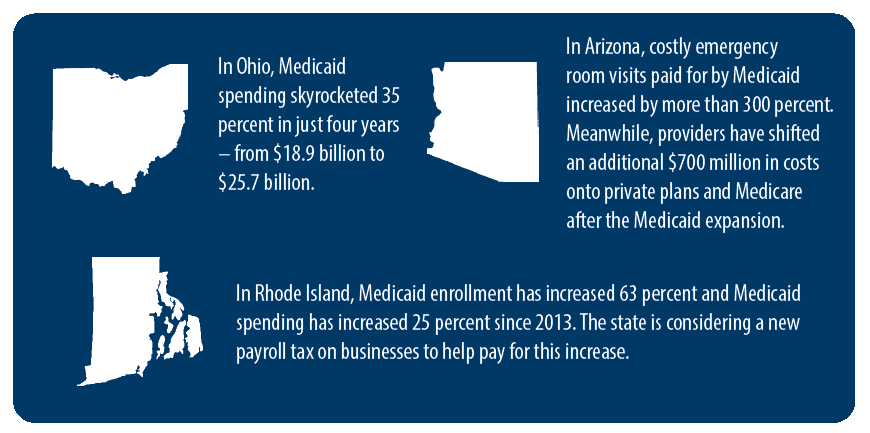

Evers’ budget accepts the federal Medicaid expansion under Obamacare while significantly increasing spending on a wide range of programs. The Medicaid expansion has been a costly proposition for states that accepted it. Medicaid spending in Ohio, for example, skyrocketed 35 percent in four years – from $18.9 billion to $25.7 billion between fiscal year 2013 and 2017. Other states have had similar experiences with out-of-control enrollment and costs to taxpayers.

The federal dollars that follow a Medicaid expansion are anything but “free money,” as advocates persistently claim.

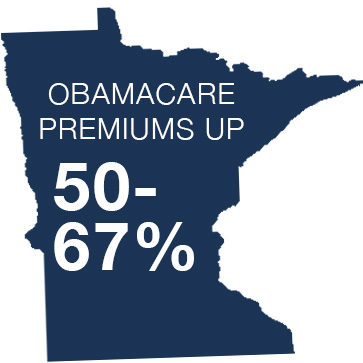

In Minnesota, individual market premiums increased 50-67 percent after Medicaid expansion, forcing the state to implement a reinsurance program costing taxpayers at least $800 million so far.

Hardly a role model to emulate, Minnesota’s embrace of “free” federal Medicaid money is actually a case study in failure. In 2017, after Obamacare’s implementation and Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton’s decision to expand Medicaid, the state found itself at risk of losing all the insurers on its individual market. On the brink of collapse, state bureaucrats allowed insurers to increase premiums by a staggering 50-67 percent.

While lower-income Minnesotans didn’t feel the pinch because of federal subsidies for the poor, the state’s middle class was due to take a financial beating. That’s why state lawmakers were forced to implement the costly reinsurance program, which to date has cost state taxpayers north of $830 million — on top of the taxes they already pay to prop up Obamacare.

Health care costs have been used as a political bludgeon, with rampant distorted claims about costs. Then-candidate Tony Evers claimed that Wisconsinites pay 50 percent more for health coverage than Minnesotans, a claim rated as “Mostly False” by Politifact. Evers was only looking at a small slice of the population – those on the so-called Second Lowest Cost Silver Plan (SLCSP) on the individual market.

But the majority of people get their coverage through their employers. In Wisconsin, 3,191,800 individuals get their coverage through their workplace, or 57 percent of the population, the same proportion as in Minnesota.

And contrary to the rhetoric, costs are virtually the same. The average annual premium in 2017 in Wisconsin was $5,868 for an individual and $18,785 for a family; in Minnesota it was $5,832 and $18,507, respectively. Employee contributions to the cost of their plans were virtually identical between the two states.

By accepting the Medicaid expansion as Minnesota did prior to the near-implosion of its individual health insurance market, Evers’ plan travels a dangerous path for taxpayers.

Despite these and many other stark cautionary tales, the Evers budget proposes expanding Medicaid eligibility to everyone earning between 0-138 percent of the federal poverty level. In 2019, that income level is $34,638 for a family of four, making 82,000 more people eligible for the program. However, 92 percent of the population is already insured—the vast majority of them through employer-based insurance.

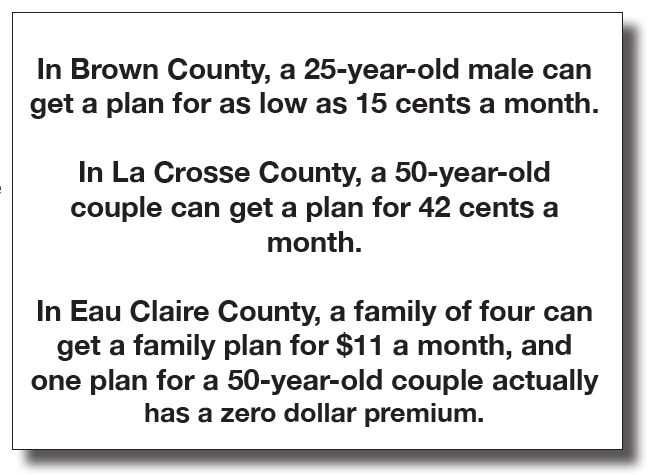

And for those not covered by their employers, subsidized plans are available for as low as 15 cents per month for those in the Medicaid expansion income range, so the 82,000 newly eligible for government assistance already have access to low-cost insurance.

That means many people who join the program would be moving backward, from self-sufficiency to dependence on government health care.

The budget asserts that expanding Medicaid will save $325 million in GPR across the biennium because of the federal government’s enhanced 90 percent match versus traditional Medicaid, a tenuous stream of dollars from a federal government already drowning in $22 trillion in debt. As with traditional Medicaid and its notoriously low reimbursement rates, the federal government is likely to back off that enhanced match in the future and leave state taxpayers holding the very expensive bag. Nonetheless, Evers’ budget proposal accepts and then immediately spends the $325 million—plus a lot more—on increased payments to health care providers and other new spending.

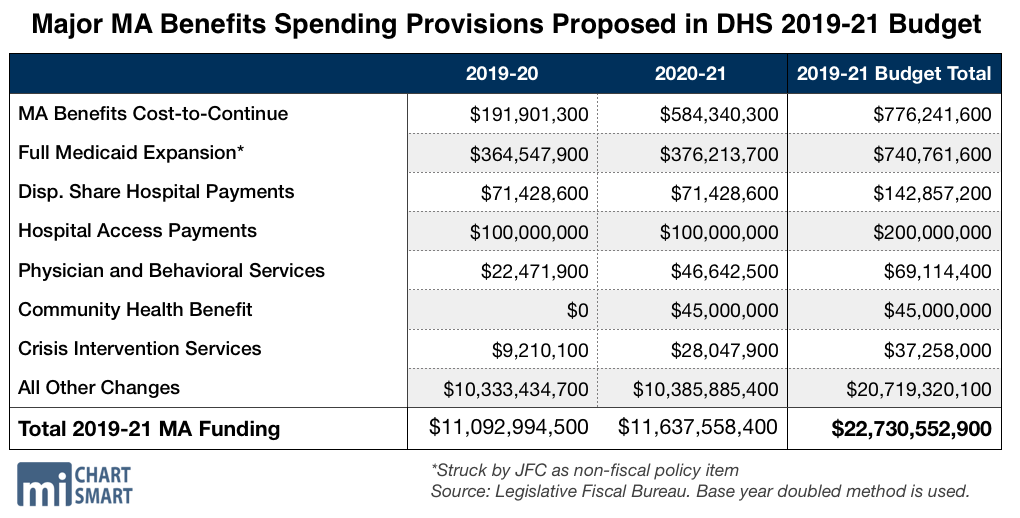

In all, the budget directs $580 million in additional dollars back to health care providers catering to Medicaid patients through the BadgerCare Plus program.

The budget spends $365 million more on reimbursement payments to hospitals serving Medicaid patients through five different, more traditional reimbursement avenues. That includes $142 million more in payments to hospitals handling a larger number of Medicaid patients than most; $100 million more for payments to acute care and critical access hospitals; $20 million more for payments to pediatric hospitals; and $1.2 million more for rural hospitals.

The proposal also hikes spending on considerably less-traditional “health” spending. It spends $45 million more for “non-medical services to reduce and prevent health disparities that result from economic and social determinants of health” such as “housing referral services, stress management, nutritional counseling, transportation coordination, etc.” It’s a significant expansion of the left’s beloved cradle-to-grave set of government programs, paid for using $45 million of precious tax dollars meant for actual health care.

The proposal also hikes spending on considerably less-traditional “health” spending – $45 million is spent on a slate of decidedly “non-medical,” cradle-to-grave programs.

The budget builds off Walker’s reinsurance program, aimed at holding down premiums on the individual health insurance market in the era of Obamacare’s skyrocketing premiums. The continuation of this Walker-era program is a not-so-subtle admission that Obamacare has failed spectacularly to “bend the cost curve down,” and that failure is costing Wisconsin taxpayers dearly. The budget buttresses the program with $200 million in all funds spending for the Office of the Commissioner of Insurance in the second year of the budget, $34 million of that GPR.

The spending plan includes an effort to lower prescription drug prices, in large part through government mandates. It proposes requiring drug companies to justify price increases, disclose proprietary information like production and marketing costs, and requires the OCI to post the information in the name of transparency. It also requires pharmacy benefit managers to register with the state and “disclose price concessions they receive from drug companies” and calls for importing generic drugs from abroad to Wisconsin.

The budget makes an effort to expand access to dental care, an area in which Wisconsin lags the nation. It spends a lot of money to do so—$43 million. The plan implements a dental therapy license in Wisconsin to increase the dental professional workforce, a market-driven option MacIver summarized in a policy brief last year, but Evers’ proposal also comes along with a hefty price tag. It spends $1.5 million to subsidize educational institutions that add a dental therapy program, with the goal to “put Wisconsin on the cutting edge of this emerging career field…” In addition to expanding spending to the tune of tens of millions of dollars for dental care under BadgerCare Plus and Medicaid, the budget also increases spending on a series of programs aimed at in-need populations and at grants for dentists who practice in rural areas or provide care to the disabled.

In addition, the proposal includes a variety of provisions aimed at behavioral and mental health care and substance abuse treatment; it spends $69 million more for reimbursement rate increases for Medicaid recipients seeking mental and behavioral health care.

Welfare Reform

DHS runs programs such as FoodShare and FoodShare Employment and Training (FSET) as well as the behemoth Medical Assistance program that includes BadgerCare.

DCF runs programs like Wisconsin Works, a job training program for low-income parents and pregnant women. All-funds spending at the agency would increase by $213 million to $2.83 billion, an 8.1 percent increase. In terms of state dollars alone, the agency would spend $957 million GPR over the biennium, an increase of $27 million or 2.9 percent. Positions at DCF increase by just two full-time equivalents over the biennium, to 988.16 total government jobs at the agency.

Welfare reforms enacted under Walker also attempted to nudge people off government health care and into private plans offered through employers.

But a series of critical Medicaid reforms enacted under Walker are also repealed wholesale by Evers’ budget, despite protections enacted during December’s extraordinary session.

Medicaid work requirements largely mirror those for FoodShare benefits and expand on the mantra that people seeking expensive help from their fellow Wisconsinites should be expected to make an effort to be self-sufficient.

Among the reforms struck by Evers’ budget are work requirements for Medicaid eligibility. Walker increased from 20 to 30 hours a week the time that able-bodied adults (ages 19 to 49) without children must be working, training for work, or looking for work to receive BadgerCare health insurance. That’s the federal maximum, as even Democrats in Congress recognize that 30 hours is not too much to ask for. Evers’ budget rolls that back.

The work requirements largely mirror those for FoodShare benefits and expand on the mantra that people seeking expensive help from their fellow Wisconsinites should be expected to make an effort to be self-sufficient.

Walker had also sought the federal government’s permission to charge a small amount of money for Medicaid benefits for a subset of those below the poverty level. The nominal premiums of $8 for households earning from 51-100 percent of the federal poverty level would give recipients at least a small financial stake in their own benefits and are a step toward reducing the “benefits cliff” that strikes people who climb the economic ladder but are faced with losing generous benefits. Evers’ budget strikes that reform.

The budget also goes easy on child support scofflaws—it eliminates a requirement that Medicaid recipients be in compliance with child support orders. JFC pulled that item out as non-fiscal policy in early May.

It also eliminates minor co-pays for non-emergency medical services, and Medicaid Health Savings Accounts are eliminated entirely. Both were enacted with the intent of injecting consumer choice into government health care by forcing recipients to shop around for providers. That, in turn, sought to put a crimp on providers who offered poorer quality services at inflated prices. Those ideas were pulled by JFC, as well.

Walker made welfare reform a focus of his administration, especially as the economy improved and made it easier for people on this program to achieve self-sufficiency.

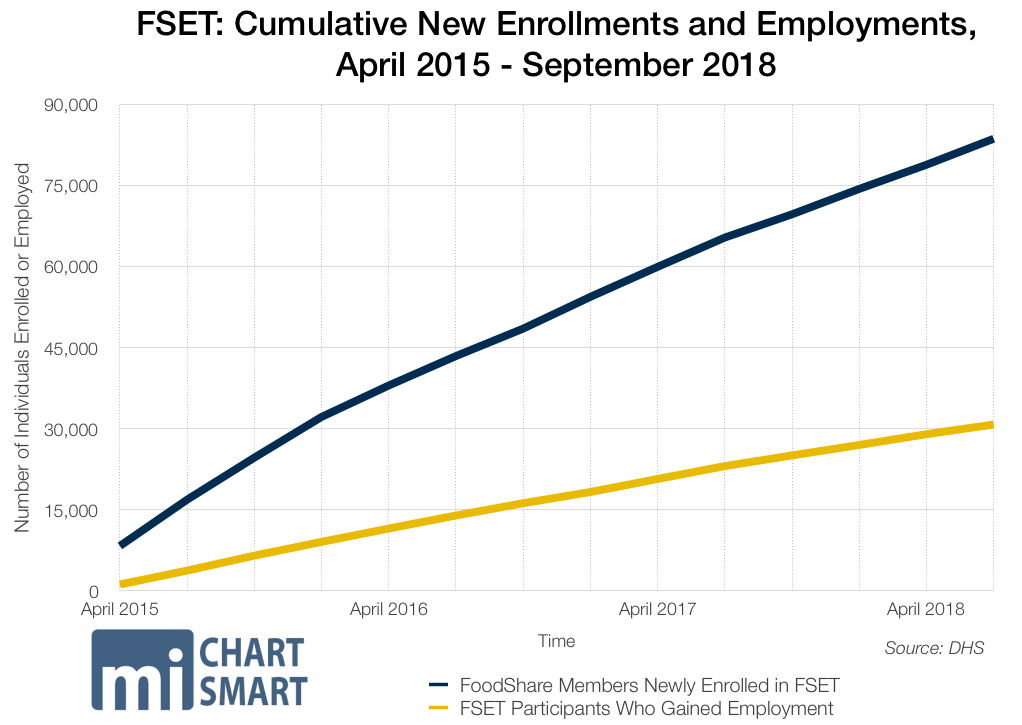

In April 2015, certain able-bodied individuals had to begin satisfying work and drug screening requirements to receive FoodShare, colloquially known as food stamps. Individuals who did not comply with work requirements for three months in a 36-month period become ineligible for those benefits. Individuals would have to work, receive job training, or a combination of both for an average of 80 hours per month to retain benefits.

In short, they would have to make an effort to earn what the taxpayers of Wisconsin were generously providing them.

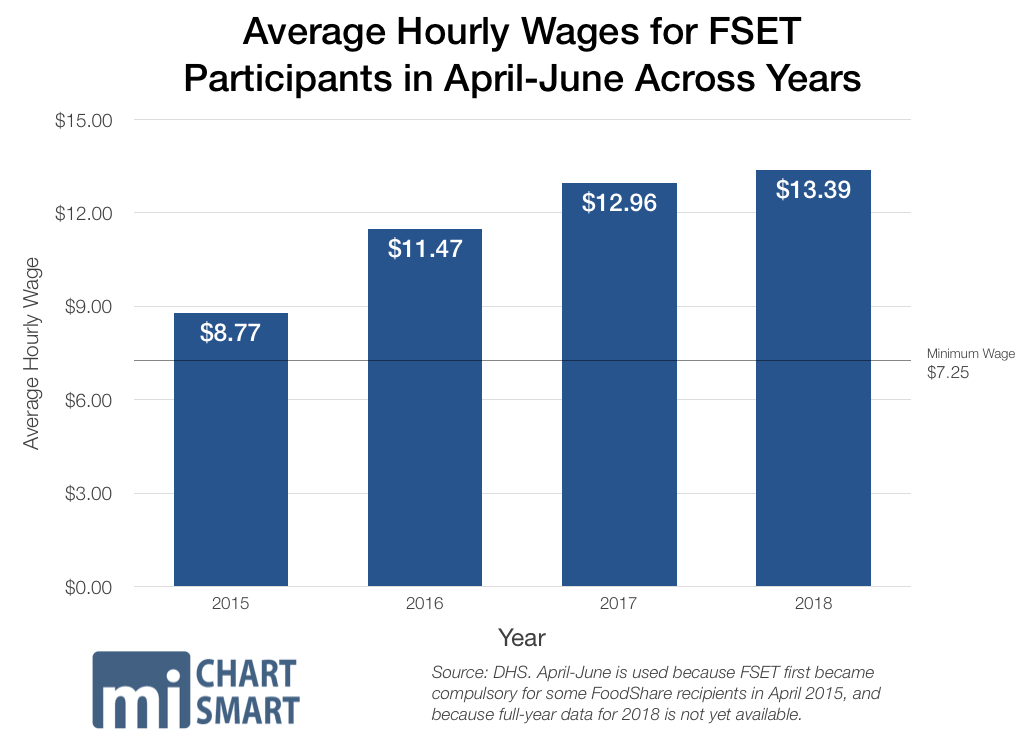

The largest job training program in the state is the FoodShare Employment Training (FSET) program. Wisconsin’s DHS has regularly reported on average FSET wages and weekly hours, both of which have increased consistently. FSET participants earned an average $13.64 per hour, nearly double the state minimum wage, according to the most recent data available.

Almost 31,000 FSET participants have gained employment since the state began tracking data in 2015.

Originally, able-bodied adults with no dependents were the only individuals required to work or participate in job training for a total of 80 hours per month. That pool later expanded to able-bodied adults with school-aged dependents (ages six to 18).

Evers’ plan strips back some of the work requirements for FoodShare participants. Able-bodied individuals with school-aged dependents would no longer have to satisfy work requirements; only those without any dependents will still have to comply.

While Evers rolls back the vast majority of welfare reforms made under the Walker administration, keeping work requirements for able-bodied adults without dependents could be considered a casual nod to the success of those reforms. Still, the remaining requirements are a far cry from the robust employment training prioritized under Walker.

In addition, all drug screening requirements are repealed under the proposal. And like in his Medicaid proposal, Evers’ plan also repeals the requirement that individuals be in compliance with child support orders in order to receive FoodShare benefits.