No push to return all children to in-person instruction or what we do to make up for the lost year of learning

Massive spending increases, attacks on school choice, and paving the way for property tax hikes

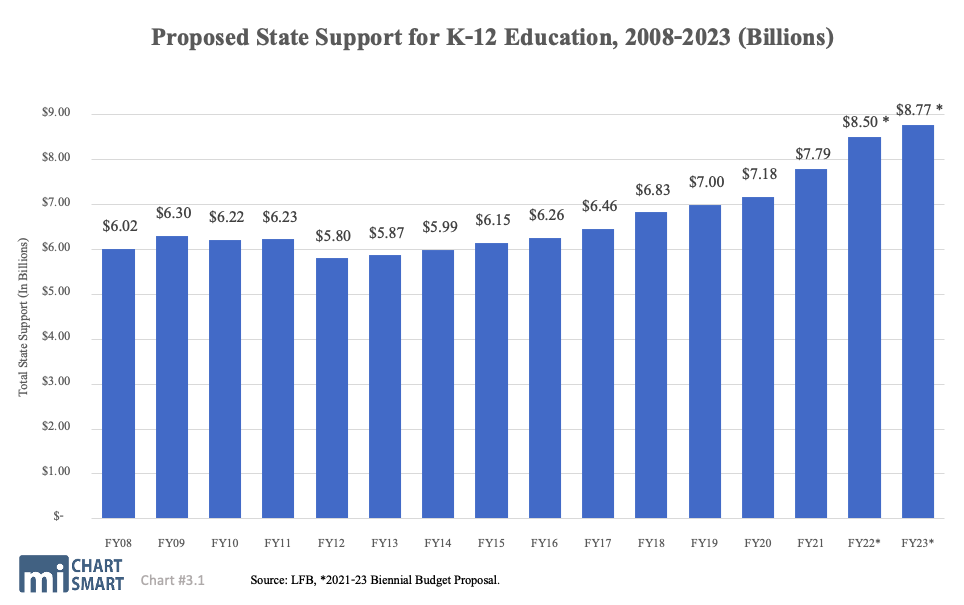

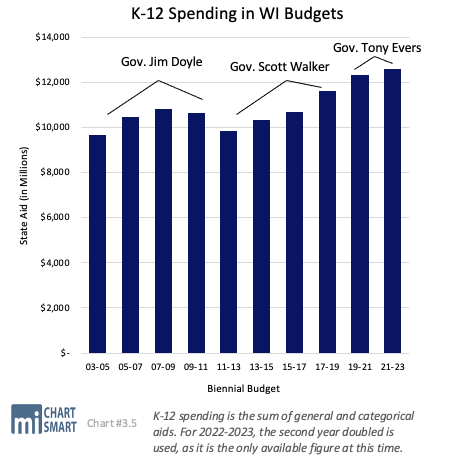

Historic spending increase would be on top of large K-12 funding increase included in the last two budgets

Special Education funding to increase by an astounding 158%

March 3, 2021

By Ola Lisowski

Gov. Tony Evers’ second biennial budget is out, and it’s a doozy for taxpayers. We’ve already covered what you, the taxpayer, need to know about the budget as a whole, and now it’s time to examine the important issue of K-12 education.

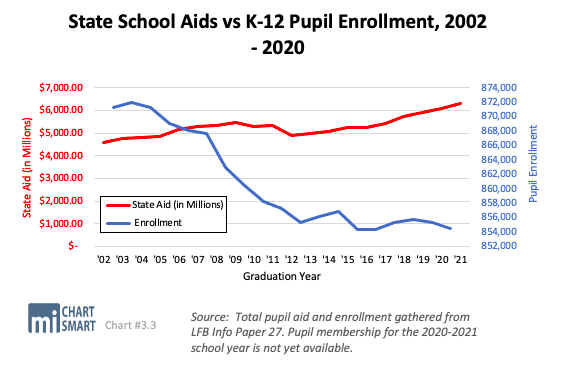

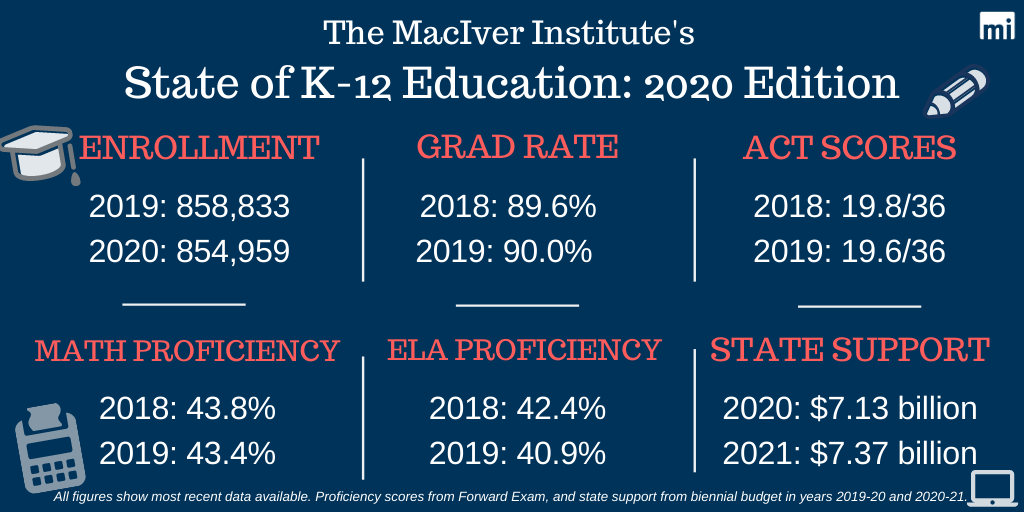

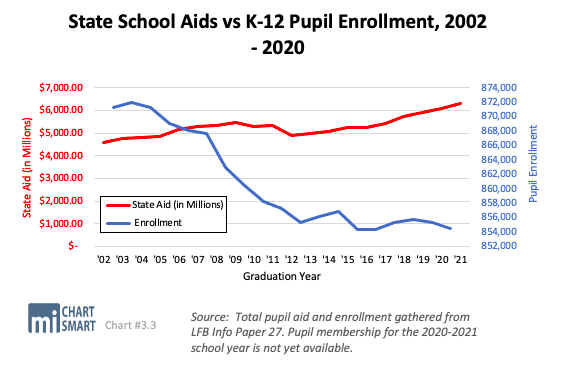

Evers was the state superintendent for the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) before becoming governor, so it’s no surprise that he’s offering plenty of costly funding increases to public schools, despite plummeting public school enrollment and more than $220 million in CARES Act funding. The governor again takes the opportunity to attack the popular school choice programs in more ways than one.

It’s also surprising how little the former superintendent’s budget discusses the negative impacts that COVID-19 and virtual learning have had on Wisconsin children and their academic progress. By now, most Wisconsin students have been learning virtually for almost a full year. The Evers budget doesn’t address that reality, nor does it make any push toward a return to in-person learning. Let’s dive in.

The Basics

Evers’ massive spending plan would send more than $17.3 billion to DPI over the biennium. In base year doubled math, that’s a $1.7 billion, or 11 percent, increase over the prior budget. The agency would hire one more position, bringing total full-time equivalent (FTE) employees at DPI to 644.

That’s right—in a year when thousands of students left public schools in pursuit of other options, the state of Wisconsin wants to send $1.7 billion more to those schools.

Not surprisingly, Evers’ proposal picks up much of what DPI itself asked for in its agency request several months ago. Namely, the governor would increase general aids to schools in both years of the budget, and restore a requirement that the state pay at least two-thirds of school revenues.

The largest single line-item increase in DPI’s budget is for special education categorical aid, which would increase by $710 million over the biennium. That funding would bring reimbursement rates to 45 percent in 2022 and 50 percent in 2023. The previous budget increased that fund by $96.9 million, for reimbursement rates to 26 percent in 2019 and 30 percent in 2020, which brought special education funding to $450 million.

Evers would increase general aids by $612.8 million over the biennium. He would also increase per pupil categorical aids $55.8 million to fund a per pupil payment of $750 in both years, plus another $75 for every economically disadvantaged student.

His proposal would also increase high-cost special education reimbursement to 40 percent in 2022 and 60 percent in 2023, for a total of $9.56 million.

The bulk of state school funding goes through what’s called general aids or the “equalization aid formula,” which is meant to “equalize” local school funding. In other words, most of that funding goes toward property-poor districts like Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS). Categorical aid, on the other hand, is only tied to student enrollment, and is sent to all districts equally regardless of wealth.

Property Tax Hikes Coming

As we wrote in our budget overview, the era of Gov. Walker’s commitment to freezing property taxes is over. Evers’ budget would open the door for property tax increases in more ways than one, including letting local units of government raise property taxes by at least 2 percent. A slew of property tax hikes tied to K-12 schools could also be on its way.

Aside from state aids, local property taxes are the other major source of K-12 school funding. In order to keep the lid on local property taxes, the state put revenue limits in place back in the 1990s. Revenue limits contain spending increases at the school district level, protecting local property taxpayers from large tax increases every year. Increasing revenue limits means at the state level that school districts can tax more per student at the local level. It’s extraordinarily rare for districts not to levy as much as the state allows, which means that property taxes statewide are very likely to increase with the total increased levy authority.

Evers would increase revenue limits by $200 per student in the first year and another $204 per student in the second year. His budget would also tie the revenue limit adjustment to inflation beginning in 2024, so this local property tax increase will automatically occur every year without a vote of the Legislature.

The budget would also increase the low revenue ceiling from $10,000 to $10,250 in the first year of the budget, and $10,500 in the second year. Evers’ first budget raised the revenue ceiling from $9,400 in fiscal year 2019, to $9,700 in 2020, and $10,000 in 2021. According to the Evers Administration, 140 districts out of the 421 total districts across the state would be allowed to increase their property taxes under this provision.

Legislators have long pushed for that change, arguing that certain districts which spent less when revenue caps were put into place have been disadvantaged since the 1990s. Gov. Walker’s commitment to lower property taxes each year was one of the biggest obstacles for those who would increase revenue limits.

The nonpartisan Legislative Fiscal Bureau (LFB) has not yet released its estimate showing how much these changes would increase statewide revenue limit authority and average property bills, but we anticipate that for taxpayers, it won’t look pretty. After a year when hardworking Wisconsinites lost their jobs and struggled to keep food on the table, the state is poised to increase property taxes once again.

Using Pre-COVID Enrollment Counts to Skew Funding

Before COVID-19 hit, public school student enrollment had been steadily falling for years, by about 0.5 percent of total headcount each year. In the last year, public school enrollment plummeted as families fled in search of other options.

Full-time total enrollment (FTE) at public schools, which currently stands at 809,104 full-time-equivalent students, fell by 32,845 in 2020, a 3.9 percent drop from 2019. Enrollment drops varied between age groups, with 4K and pre-kindergarten enrollment falling the most, at 15.6 percent compared to last year.

A 4 percent fall might not sound like much, but compared to an average of just 0.5 percent, the change is quite dramatic.

However, Evers wants to fund public schools based on pre-COVID headcounts. That means schools would receive millions of dollars for students they are not educating.

DPI’s budget request suggested allowing districts to use the greater of 2019 or 2020 pupil count for revenue limit purposes, eliminating the impact of the enrollment drop in funding levels moving forward. Funding to schools is based on a three-year enrollment average.

In justifying the changes, DPI’s budget seemed to assume that public school enrollment will rise back to pre-COVID levels after the health crisis is over. Evers’ proposal makes the same assumption.

Evers wants to fund schools based on pre-COVID headcounts. That means schools would receive millions of dollars for students they are not educating.

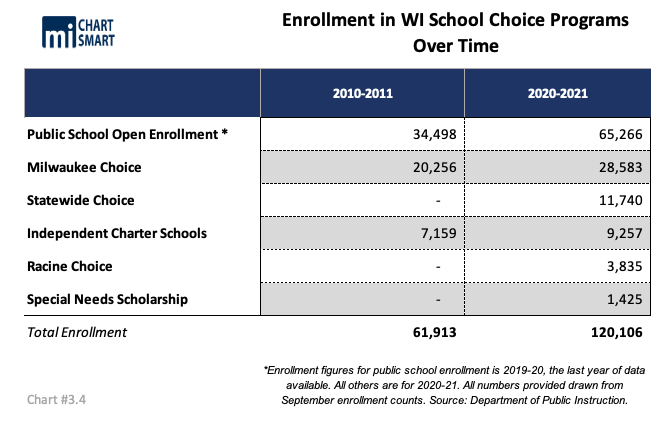

While public school enrollment fell this year, enrollment at parental choice programs and independent charter schools increased, albeit at lower levels than typically seen. Independent charter schools saw their total headcounts increase by 1.6 percent overall. Enrollment in parental choice programs increased by 5.9 percent. A total of 45,954 students now participate in Wisconsin’s private school choice programs, and 9,257 students are enrolled in independent charter schools.

Evers would put the brakes on those programs, even as Wisconsinites have shown their interest in using educational choice amidst the public health crisis. As of the most recent headcount last fall, 28,583 students participate in the Milwaukee choice program, 3,835 in Racine’s choice program, 12,111 in the statewide choice program, and 1,425 in the Special Needs Scholarship Program (SNSP). Notably, participation in the statewide program increased by a stunning 24 percent this year, and participation in the SNSP increased by 36 percent.

Parental Choice

Despite their popularity, for the second budget in a row, Evers is proposing to halt enrollment in Wisconsin’s popular school choice programs.

Beginning in 2023, his budget would freeze enrollment at 2022 levels in the Milwaukee, Racine, and statewide programs, as well as in the SNSP. In addition to capping SNSP enrollment, the budget would also require that new schools entering the SNSP also participate in another choice program at the same time.

Many private schools have proceeded with in-person instruction all year while many public schools decided to start the year with virtual instruction and some remain closed to in-person learning today. This provision to cap choice enrollment would make sure that more students don’t leave their public schools for options that might better suit them.

DPI did not include any of these changes in its agency request of Gov. Evers, but actually proposed numerous small changes that school choice supporters have asked for.

Evers is proposing adding more information about private choice programs on a taxpayers’ property tax bill. That plan has long been pushed by critics of the school choice programs.

The budget would require that all teachers who teach at private schools in any of Wisconsin’s parental choice programs be licensed by DPI, beginning in 2024.

He would also eliminate the Office of Educational Opportunity, which authorizes independent charter schools when a local school board will not.

New Programs, Increased Funding to Existing Programs

Evers plans to increase sparsity aid by $19.96 million, and create a new tier of funding for sparsity aid, an idea which legislators have supported in past years.

Under the proposal, DPI would create a new tier of funding so that districts with student enrollment of 746 up to 1,000, and fewer than 10 students per square mile, would receive an extra $100 per student. Plus, if a district loses eligibility for sparsity aid because it no longer meets sparsity requirements, it would qualify for a one-year “stopgap” payment of 50 percent of the prior year’s payment.

Reimbursement rates for pupil transportation aid would go up, and high-cost transportation aid would increase by $4 million.

Evers proposes creating several new programs, too. One new grant program would spend $20 million to support out-of-school time programs. Another line item would spend $20 million to create another energy efficiency grant program just for schools.

The state would also create a new categorical aid program for driver education, worth $2.9 million, as well as a new supplemental nutrition aid program for $4.86 million. One new program would spend $750,000 to support professional development to license more computer science teachers.

The budget would create a new Agency Equity Officer position in the Office of the Superintendent, totaling $144,800.

Evers would also spend $400,000 in tribal gaming revenue to create a grant program that assists school districts in replacing race-based nicknames, logos, mascots, and team names.

Other funding proposals in the plan include:

- $46.5 million to expand the School Mental Health Categorical Aid Program

- $28 million for English Learners

- $7 million for School-Based Mental Health Services Grants

- $6.5 million for public library systems

- $5 million for school breakfast reimbursements

- $1.5 million for the Special Education Transition Readiness Grant

- $1.4 million for transportation aid for open enrollment and Early College Credit program participants

- $1 million for mental health training programs

- $1 million for academic and career planning

- $750,000 for a new grant program to expand licensing of bilingual and English as a Second Language teachers

- $380,000 to expand City Year Milwaukee, a non-profit student support organization

Several policy items don’t come with state funding attached, including one provision which recommends incorporating climate change information, and the human impact on climate change, into model academic standards. The budget also recommends increasing American Indian studies curriculum in Wisconsin school districts, and would require that schools in the parental choice program provide instruction on American Indian studies in elementary and high school grades.

One of the few policy items that could potentially save taxpayers money is a provision requiring the Group Insurance Board to study the impact of requiring all school districts to participate in the State of Wisconsin Group Health Insurance Program. The Group Insurance Board would conduct an actuarial study to assess potential costs and savings to school districts and plan participants if they were added to the state health insurance plan.

Overall, Evers’ second budget proposal shows his eagerness to hike taxes and government spending as Wisconsinites struggle to stay afloat. The request makes no mention of the hundreds of millions in CARES Act funding that schools received, nor does it mention the massive education funding increases in the last three state budgets. Potential savings realized from Act 10 are nowhere to be seen, nor is any commitment to returning students to in-person learning as soon as is practicable.

Instead, the document pledges for more of the same. For Wisconsin students and taxpayers who have been hurting over the last year, that’s too bad.