A MacIver Institute Perspective by Bill Osmulski

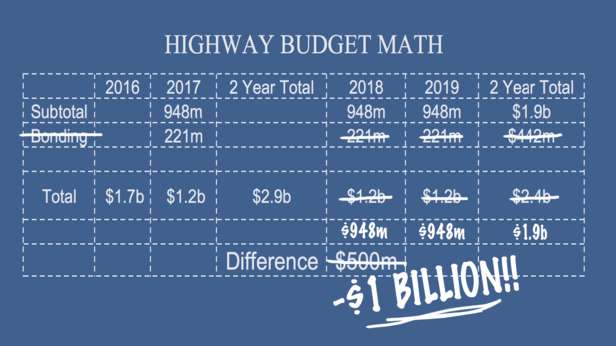

A billion-dollar shortfall in the next transportation budget started the debate about raising Wisconsin’s gas tax, which was so explosive, no one seemingly had the time to confirm there is a billion-dollar shortfall. If they had, the current debate might not be centered on the gas tax, but instead on how we fund roads in the first place, because there’s only a shortfall if you change the way Wisconsin funds transportation.

The current 2015-2017 state budget spends $2.8 billion on highways, and $855 million of that comes from bonding. That means about 30 percent of everything Wisconsin spends on roads is borrowed, and there are those who believe the state should not be borrowing at all to pay for roads. That was the cover story for a peculiar request the Legislative Fiscal Bureau received last summer.

Even though the DOT was about to submit a new budget request in less than two months, Fiscal Bureau was asked to project what the DOT’s budget would look like under an unlikely set of circumstances. The request wanted the Fiscal Bureau to omit all bonding under a cost-to-continue scenario. The result was a $939 million difference between the current budget and the next.

The billion-dollar transportation deficit was born.

That number started the narrative that Wisconsin has a transportation funding crisis. It didn’t matter that two months later the DOT presented its actual budget request that included spending projections, revenue estimates, current federal funding commitments, and existing bonding. That request also indicated there would be a shortfall, but at $449 million, it was less than half of the previous projection. When Governor Walker presented his budget proposal, he included $500 million in new transportation bonding to fill that gap, which would be the lowest amount since the 2001-2003 budget. It would also mean no delays on major projects currently underway.

Still, the fabricated billion-dollar deficit dominates coverage of the transportation budget, and it continues to frame the debate over the gas tax. Framing the transportation debate this way benefits those who want to raise the gas tax. However, they will still readily point to bonding as an underlying concern.

“It is more conservative to pay for projects today than it is to borrow the money and make our children pay the price. But for far too long under Democratic and Republican leadership, the state has relied too heavily on bonding. According to the Legislative Fiscal Bureau, Wisconsin will spend roughly 20 cents on every transportation dollar on debt service for this fiscal year,” Vos said in a September 15, 2016 press release.

The Walker Administration, on the other hand, argues that transportation bonding is no different than taking out a mortgage for your house. The idea is you spread out the expense over the amount time you plan to use it.

Bonding is the one of the most common ways states fund transportation projects. There are only five states that don’t use transportation bonds at all. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) released a report in November that found bonding to be one of the most successful approaches to transportation funding and finance.

Meanwhile, heavy reliance on fuel taxes is considered one of the least successful approaches to transportation funding according to AASHTO. In fact, many experts say fuel taxes are becoming obsolete as people drive less and cars become more fuel efficient. Even the supporters of raising the gas tax in Wisconsin admit it’s not a perfect solution.

“Even though a lot of conversations have been about the gas tax being a declining revenue source or a dying revenue source long term, there are limitations to every different option that’s out there,” Representative John Nygren, Co-chair of the Joint Committee on Finance, told the Milwaukee Press Club at a luncheon on January 11th.

When it comes to options, Wisconsin has 19 different sources of revenue for its Transportation Fund. That’s more than any other state in the country, according to AASHTO. These include aircraft registration fees, airline property tax, drivers and vehicle records fees, driver’s license and state ID card fees, fines for truck size and weight violations, fuel tax, general funds, interest income, outdoor advertising revenues, oversize/overweight truck permit fees, passenger rail station sponsorship, passenger vehicle fees, petroleum inspection fund revenues, property sales, railroad property taxes, state rental vehicles fees, taxes on alternative fuels, taxes on aviation fuels, and truck registration fees. This is expected to bring in a total of $3.5 billion over the next biennium. When it comes to user fees specifically, Wisconsin’s collections of user fees per lane mile are comparable to its neighbors.

Wisconsin has 19 different sources of revenue for road funding. More than any other state in the country. pic.twitter.com/y4wG8KI0qW

— MacIver News Service (@NewsMacIver) March 2, 2017

Wisconsin raises similar revenue from user fees per paved lane mile of road as neighboring states. pic.twitter.com/6UohbcLBqP

— MacIver News Service (@NewsMacIver) March 2, 2017

However, when we compare total highway spending (including administrative and debt service costs) per lane mile to road quality, we see that Wisconsin spends more for poorer quality roads. The state is clearly not getting a good deal on its roadwork, and it begs the question why? Fortunately, lawmakers sensed something was not right at DOT and ordered an audit last year.

Why does Wisconsin pay more for poorer roads? pic.twitter.com/fcUtH0ycNg

— MacIver News Service (@NewsMacIver) March 2, 2017

That audit came back in January 2017, and it was, in a word, devastating. The auditors found the DOT regularly breaks state law in budgeting, negotiating, communicating, and managing contracts. Among these statutory violations: the department does not always solicit bids from more than one vendor, it does not spread out solicitations throughout the year, it does not post required information on its website, its cost estimates to the governor are incomplete, and it skips steps in the evaluation process for selecting projects. These practices manifest themselves through an inescapable reality: the cost of major projects tends to double after the DOT gets approval from the governor and legislature to proceed. The auditors looked at 16 current highway projects and found they are over-budget by $3.1 billion.

Assembly Speaker Robin Vos said the audit indicates the state isn’t spending enough on transportation.

“Construction delays are driving up costs unnecessarily, our road conditions are only getting worse and a long-term solution is needed. It’s clear Wisconsin is trying to do too much with too little and taxpayers are not getting their money’s worth,” he said in a release.

When the Joint Audit Committee held a hearing about the DOT on February 21, 2017, Rep. Nygren described the audit as “the tip of the spear” in the transportation funding debate. However, after acknowledging the need for reforms, he, too, claimed the audit suggests the need for even more transportation funding.

“Could it also be interpreted that because costs are not being estimated appropriately, that the actual projected shortfall that we’ve discuss of about a billion dollars is actually underestimated?” he asked the auditors. They answered that was outside the scope of their investigation.

Senator Chris Kapenga responded that “giving them more money would just absolutely be the wrong thing to do at this point,” until the new DOT Secretary has a chance to reform the agency and the legislature implements new oversight measures.

This light sparring has been typical of the DOT debate so far. That’s because the bottom line is we don’t know what the bottom line is. The side arguing for more highway spending hasn’t provided a solid figure. We often hear about that fabricated billion-dollar deficit, but now there are some, like Rep. Nygren, who say even that might not be enough. On the other hand, Rep. Vos has suggested $300 million might be a realistic amount given the governor’s budget criteria.

The governor has been firm and public in his opposition to raising taxes or fees for transportation. However, in December he made a comment that the only reason he might reconsider is if there were tax cuts in other parts of the budget to offset it. Vos took that comment and ran with it. He announced the $300 million target a month later, and Walker quickly clarified there was no deal to begin with.

Hypothetically, if Wisconsin were to boost highway funding by $300 million and it all came from a gas tax increase, the state’s gas tax would have to go from 32.9 cents to 37.7 cents a gallon. That would give Wisconsin the eighth highest gas tax in the country. Of course, Vos’ plan could spread that $300 million out across various taxes and fees in order to soften the blow. No one’s really talked about that $300 million for over a month now, but then again, Vos and his allies are playing this very close to the vest.

When Nygren was asked about his side’s lack of a definitive proposal to increase transportation funding at the Milwaukee Press Club luncheon, he simply responded, “We have been more about keeping all options on the table and having that dialogue, rather than choosing one path or one plan over the other.”

Yet, the only option we continue to hear is raise the gas tax, and the best evidence to support that option is the fabricated billion-dollar shortfall. And nobody has definitively promised if we raise the gas tax, there will be no transportation bonding – which supposedly initiated this debate in the first place.