[bctt tweet=”A Digital Technology Committee votes to end Madison’s pursuit of a $173 million citywide broadband project after costly projections rise and cold, hard reality sinks in. #wiright #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”A Digital Technology Committee votes to end Madison’s pursuit of a $173 million citywide broadband project after costly projections rise and cold, hard reality sinks in. #wiright #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

MacIver News Service | Sept. 28, 2018

By M.D. Kittle and Chris Rochester

MADISON – Madison’s costly broadband-for-all dream has gone out “with a whimper and not with a bang.”

On Wednesday, the city’s Digital Technology Committee approved a motion to not pursue a Fiber to the Premises (FTTP) plan but to explore smaller, more targeted approaches to deal with Madison’s so-called “digital divide.”

[bctt tweet=”In June, the panel learned that the estimated expense to build a so-called “dark fiber” FTTP network that “passes each residence and business” in Madison, is estimated to cost $173.2 million.” username=”MacIverWisc”]

“With a whimper and not with a bang the project comes to an end,” said Barry Orton, chairman of the subcommittee created to explore a city-led effort to bring broadband to every corner of Madison.

What the subcommittee ran into was financial reality.

In June, the panel learned that the estimated expense to build a so-called “dark fiber” FTTP network that “passes each residence and business” in Madison, is estimated to cost north of $150 million – $173.2 million all told when bonding costs are added in.

A consultant’s report found that none of the bids from the private broadband service providers interested in partnering with the city “would cover the entire bonding amount.” None comes close, according to the report. Private provider fees to link high-speed Internet service to customers who seek it would bring in about $52 million, less than a third of the total cost for the build-out alone.

Orton said subcommittee members weren’t surprised by the cost estimates, but they were disappointed. They had assumed that the city’s existing Metropolitan Unified Fiber Network (MUFN), a collaborative metro fiber-optic network, would have offset more of the FTTP development costs.

It was one of many incorrect assumptions Madison broadband-for-all proponents have made over the past few years.

Leaders of the liberal city had high hopes for a $500,000-plus pilot program to bring low-cost, high-speed Internet to four low-income neighborhoods. The program crashed and burned when the city learned that many of the rental properties in the targeted areas already had contracts with private broadband providers. Ultimately, the program signed up just 19 customers.

But the cold shot of reality came from the consultant’s report.

“It really wound down to the fact that we would not only need to borrow money at a significant level,” Orton said, but taxpayers would be on the hook for even more.

The first chunk of the $173.2 million in bonding would be covered through fees from a partner tapped to build out and oversee the network. But the larger part would have to be “borne by citizens” through a special assessment, Orton said. That was apparently a fiber line too far for the committee.

“That special assessment would be to any home or business passed by the network, but that still wound up being a significant amount of money, to the point where the subcommittee at least felt that it was not going to be feasible to discuss with the (City) Council having a particular project,” Orton said.

[bctt tweet=”City officials had expected federal taxpayers to pick up the tab for a significant portion of Madison’s government broadband scheme. Then Donald Trump won the presidency.” username=”MacIverWisc”]

He also blamed the political climate for funding gaps, arguably exposing the thought process of big-government Madison bureaucrats and city leaders.

“We were hoping for some kind of significant support on the federal level,” Orton told the full committee. “If you remember, two years ago when we were discussing this there was a lot of money being talked about for infrastructure.”

“As we all know, the election went to a different individual (Donald Trump) and to a party (Republicans) that has a different approach to infrastructure and its financing and its importance,” he added.

In other words, city officials expected federal taxpayers to pay for a significant portion of Madison’s government broadband scheme.

Some committee members have rightfully asked, is the city trying to create a solution in search of a problem?

Broadband experts say Madison is one of the most digitally connected cities in the country, thanks to the private sector, not the government. An earlier survey found that about 95 percent of city respondents had some form of Internet connection, with 89 percent reporting home Internet service.

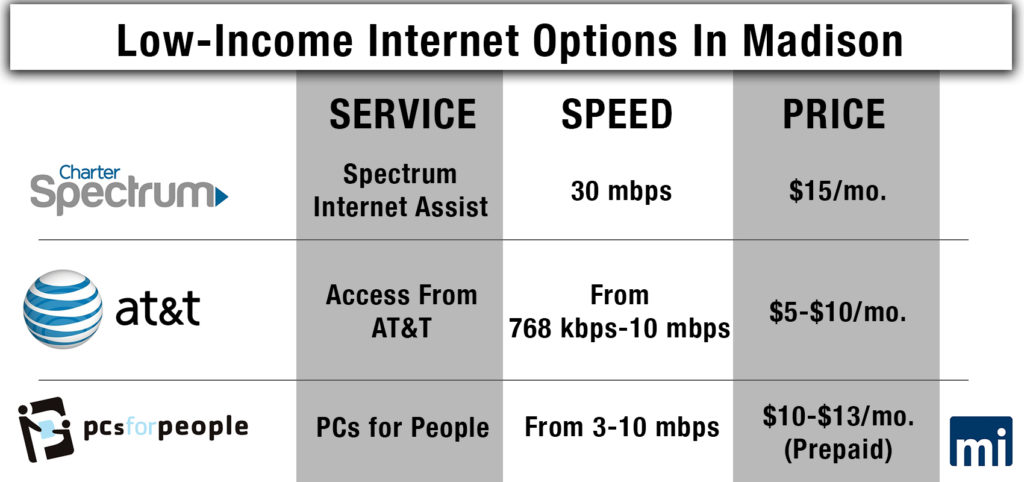

And in recent years, private providers have rolled out low-cost, high-speed broadband service aimed to serve the low-income populations city leaders say they want to help. In Madison, AT&T and Charter Spectrum both offer service options for low-income households.

There are also many painful lessons learned from cities that have been down the troubled road of municipal-controlled broadband. Broadband boondoggles litter the big government landscape. Perhaps the most glaring example is Burlington Telecom, the debt-ridden, government-owned Internet network of Burlington, Vt. Taxpayers were buried in millions of dollars of debt after the municipal system’s profits began to dry up a decade ago.

In 2009, the city was forced to admit it had a debt problem. It had secretly loaned $16.9 million to Burlington Telecom, according to reports. The public Internet provider failed to repay. The massive, secret bailout led to the resignation of the city’s chief financial officer.

A credit downgrade followed, as did a lawsuit from Citibank, seeking damages north of $33 million. Eventually, in 2014, the city agreed to sell Burlington Telecom and split the proceeds to pay of its debt. That sparked an internecine war among government officials and some taxpayers, who earlier this year fought the sale to a private company.

“Waste and misuse of the City’s resources will result if the Petition is granted,” a lawyer for the group wrote in March. Waste and misuse has already long dogged the government-owned network.

Madison’s municipal broadband pushers haven’t given up entirely. They are hoping to pursue smaller connections, building on the MUFN system and working closely with neighborhood associations in expanding broadband.

But the subcommittee’s pursuit of a citywide FTTP system is over. Orton recommended the full committee at a future meeting take up a motion to dissolve the citywide broadband subcommittee.