[bctt tweet=”Today, MacIver takes a closer look at Gov. Evers’ K-12 budget, which spends nearly $1.6 billion more while drastically limiting #schoolchoice. #wiright #wiedu #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

[bctt tweet=”Today, MacIver takes a closer look at Gov. Evers’ K-12 budget, which spends nearly $1.6 billion more while drastically limiting #schoolchoice. #wiright #wiedu #wipolitics ” username=”MacIverWisc”]

A whole lot more money, and a whole lot less choice

By Ola Lisowski

March 13, 2019

As former state Superintendent of the Department of Public Instruction (DPI), Gov. Tony Evers has made K-12 education a top priority in his 2019-21 biennial budget proposal. That is, as long as students attend the types of schools he prefers.

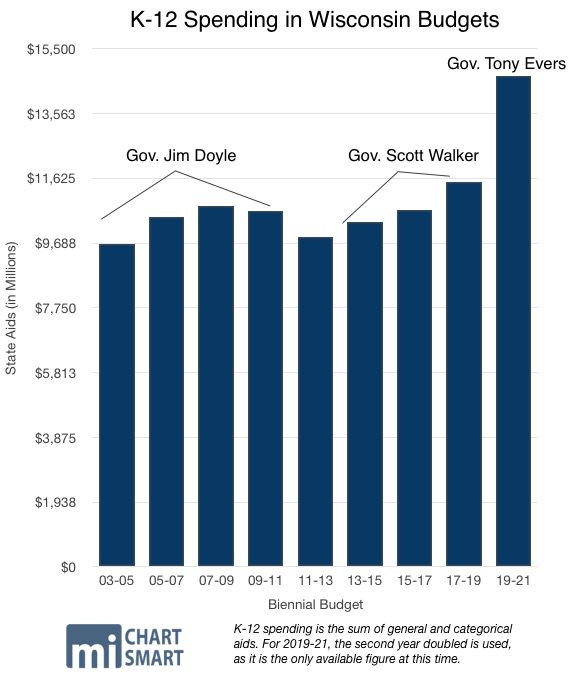

The budget would spend an estimated $15.5 billion for DPI’s programs and operations, an 11.5 percent, or $1.6 billion, increase from the current base of $13.8 billion.

The massive spending plan calls for nearly $1.6 billion more for DPI over the biennium, another record hike over the prior budget’s increase of more than $630 million. It would dramatically rework the school funding formula, based on a proposal long-championed by Evers called “Fair Funding for Our Future.” It would also drastically restrict access to educational choice.

DPI sees the largest increase in state aids of any agency in the budget proposal. Looking at general purpose revenue (GPR) alone, the budget would spend an estimated $15.5 billion for DPI’s programs and operations, an 11.5 percent, or $1.6 billion, increase from the current base of $13.8 billion.

The Legislative Fiscal Bureau (LFB) will soon release its nonpartisan fiscal analysis of the budget document, which is when full funding figures will become clear. For now, all we have to analyze is Evers’ budget document, which directly cites the $1.6 billion increase in GPR to DPI, the largest of any agency. Surprisingly, total positions at DPI actually decrease over the biennium, from 649 to 646.

Another portion of the document shows that general and categorical aids rise to $7.35 billion in the second year of the biennium. Those figures are counted slightly differently than GPR-based state aids. Confusing? We agree. Wisconsin’s school finance formula is notoriously complex. Take a look at the increase over the Doyle and Walker years in the chart below, and keep reading to learn about other policy changes for K-12 education.

A freeze on choice

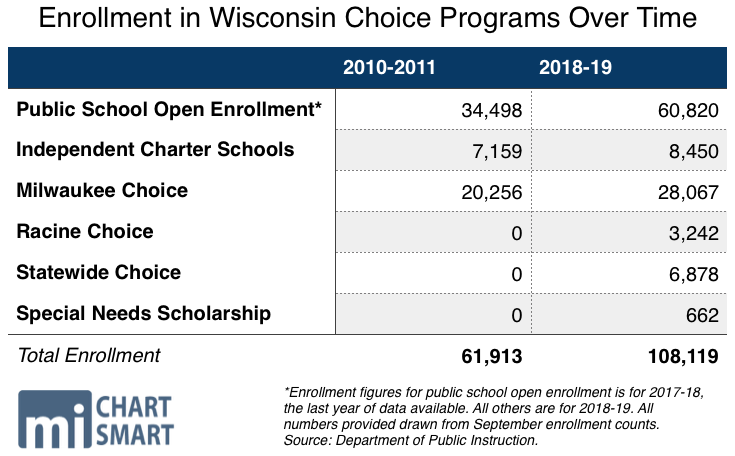

More than 38,000 low-income children attend private schools in the Milwaukee, Racine, and Wisconsin Parental Choice Programs (the MPCP, RPCP, and WPCP, respectively.)

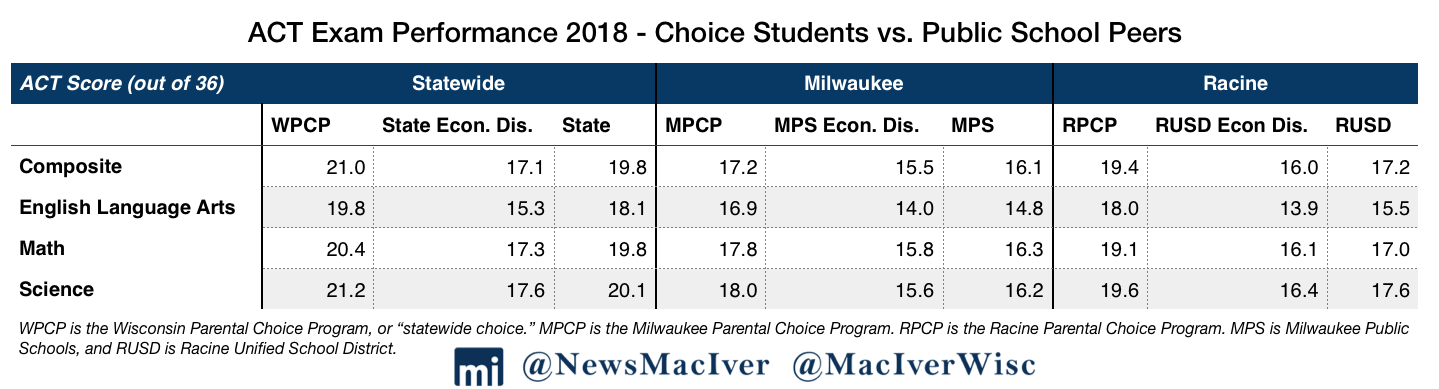

That number would freeze under the Evers plan, with the number of students allowed to participate in the three voucher programs capped at 2019-20 enrollment levels. Moving forward, new students could only attend the programs if others graduate or leave. Research shows that the programs have been incredibly popular among participating families, and students consistently post better academic outcomes than their public school peers.

Hundreds of choice students, parents, and faculty gathered in the rotunda before Evers’ budget unveiling on Feb. 28 to protest the governor’s proposals.

“I want the best school for my kids,” one mother, whose children attend Rocketship Southside Community Prep, a charter school in Milwaukee, told MacIver News Service on the night of Evers’ budget address.

Nelly Hernandez, Manager of Family and Community Engagement at Rocketship, helped translate for her friend. Hernandez added that she was also a founding parent of the school, and she wants it to stay open.

“I’m here to advocate for school choice, to put a face on this voucher, and let people know that these opportunities do mean something. They do matter,” said Kenya Green, a 2014 graduate of Hope Christian High School.

Tammy Olivas, Outreach Director for Hispanics for School Choice, thought the show of support for school choice was “amazing.”

“We got so many families that really understand what it would mean to not have the options that they have here,” Olivas said. “I’m speechless because they spoke for us…we came together to be a family and to just let everybody know that what we have is what we want. Not less.”

Students can only participate in the parental choice programs if their family incomes are below certain income limitations. In Milwaukee and Racine, families can earn up to 300 percent of the federal poverty level to qualify. For a family of four, that amounts to $75,300 for the 2019-20 school year. Outside of those two cities, the limit is 220 percent of the poverty level, or $55,220 for a family of four.

If families exceed the cap, their options are to either attend public schools, or pay out-of-pocket for a private school education.

Another section of Evers’ budget proposal would strike at private schools in a different way, by removing tax deductibility for private school tuition.

The MPCP was established in the 1990-91 school year, making it the nation’s oldest voucher program. That year, the fall headcount was 337 students attending seven schools they could not otherwise afford.

Enrollment caps for the program were lifted in 2011, and participation in the program has since soared to 28,067 students at 129 private schools. Compared to the first year, student enrollment has increased by more than 80-fold.

“I’m here to advocate for school choice, to put a face on this voucher, and let people know that these opportunities do mean something. They do matter,” said Kenya Green, a 2014 graduate of Hope Christian High School. “I want people to have the same choice that I had. Here I am, today, successful because of the opportunities that the voucher provided me.”

“I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with public school, but I’m just saying people should have a choice on where they choose to educate their kids. Public school doesn’t cut it for everyone sometimes. That’s why I’m here – to put a face on this movement and to let people know that we do have results. This voucher does matter to a lot of people.”

Today, the only program with an enrollment cap is WPCP. This year, up to 3 percent of public school students may enroll in the statewide program. If enrollment exceeds the cap, a random lottery chooses who is allowed in and who is placed on a waiting list. Thirty-nine students are currently on WPCP’s waiting list.

According to prior law, that percentage would have to increase by 1 percent annually until it is 10 percent, after which time the cap would be removed.

Evers’ plan would dramatically walk that access back, creating a cap on enrollment in the next school year. As a result, some families may be denied seats for younger siblings if no seats open up, splitting families across different schools.

Jim Bender, President of School Choice Wisconsin, highlighted the higher achievement predominant at participating private choice schools in a statement to MacIver.

“According to [Evers’] own school report card, the vast majority of the 5-star schools in Milwaukee are private schools in the choice program or independent charter schools,” Bender said. “Limiting access to these schools puts the financial and political needs of adults ahead of progress for kids.”

Choice students with special needs would be even worse off under the proposal. Evers plans to axe the Special Needs Scholarship Program after the current year.

Indeed, the most recent DPI report cards show private choice schools and charter schools outperform traditional public schools. Of the 17 MPS schools that received five stars on 2018 report cards, 10 are private choice, and four are charters. Just three traditional public schools at MPS received five stars.

On the other end of the scale, 50 MPS schools received one star last fall. Of those 50 failing schools, 10 are private choice schools, and three are charter schools. The remaining 37 failing MPS schools are traditional public schools. Under Evers’ plan, more students would be forced to attend traditional public schools.

Choice students with special needs would be even worse off under the proposal. Evers plans to axe the Special Needs Scholarship Program (SNSP) after the current year. No new students would be allowed to participate in the program beginning in 2020-21. That program allows students with special needs to attend the private school of their choice with a scholarship from the state.

Evers’ budget document asserts that the program was snuck into the 2015-17 budget without public oversight and “was created without the opportunity for a public hearing.” However, the idea was publicly vetted in 2014, with parents testifying in favor and against the proposal. MacIver was there to capture testimony.

The nonpartisan Legislative Audit Bureau audited the program in 2018. The results were glowing. Parents reported fewer negative experiences for their children compared to their time in public school. More than three times as many parents reported that they were “very satisfied” with participating private schools compared to public schools. While 6.5 percent of respondents said they were “very disappointed” with their child’s private school, 32.8 percent of parents said the same about their child’s public school.

Independent charter schools are also targeted in the budget plan. Under current law, any UW System chancellor, the City of Milwaukee’s common council, any tech college board, the Waukesha County Executive, tribal authorities, and the UW System’s Office of Educational Opportunity are considered independent bodies that can authorize new charter schools.

In Evers’ proposal, no new schools could be authorized by any body other than a school district until 2023.

In Evers’ proposal, no new schools could be authorized by any body other than a school district until 2023. Already-existing charter schools would be allowed to continue operating and adding new students. In the current school year, 8,450 students attend independent charter schools.

One City Schools is authorized by the UW’s Office of Educational Opportunity. This school year was its first operating a charter school for 4- and 5-year-old kindergarten. The school was voted Best in Madison in Child Care by Madison-area voters for Madison Magazine in 2019. One City would purportedly be unaffected by the change, but other schools hoping to follow its model would be turned down.

The most commonly used form of school choice in the state is public school open enrollment. That program, launched in the 1998-99 school year, allows students to attend public schools in a district outside their own.

This year, 60,820 students participate in the program. Public school open enrollment is not frozen in Evers’ budget request.

Other changes to the school choice programs proposed in Evers’ budget include a new requirement for all private school teachers in a participating choice program to be licensed by the state. Schools would also have to be fully accredited, not just pre-accredited as current law requires. Information about state aid that goes to private school choice programs would also be included on property tax bills.

New formula, new grants

Wisconsin’s school finance formula is notoriously complicated. Schools receive money from the state, from local property taxes, from the federal government, and several other sources. The state also sends money to individuals to offset local property tax increases.

That’s the goal of the School Levy Tax Credit (SLTC). The SLTC appears as a property tax credit on homeowners’ bills, deducting from the total amount they must pay in property taxes. The First Dollar Credit (FDC) works in a similar fashion.

Under Evers’ plan, both credits would be eliminated. The more than $2 billion spent on them in the biennium would instead flow through the equalization aid formula.

Equalization aid is designed to “equalize” local property taxes – that is to say, the aid goes mostly toward property-poor districts such as Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS). Categorical aid, such as per-pupil aid, is sent to all districts equally, regardless of wealth.

That change alone is likely to increase local property taxes.

Increasing revenue limits is another path toward higher property taxes. Evers’ budget plan would increase per pupil revenue limits by $200 in the first year and by $204 in the second.

Increasing revenue limits simply means that school districts can levy more (in layman’s terms, tax more) per student at the local level. It’s extraordinarily rare for districts not to levy as much as the state allows, so it’s likely that property taxes statewide will increase by the total increased levy authority.

Evers’ plan also increases the low revenue adjustment, a move championed by Assembly Republicans during the last budget cycle. Their plan, much less far-reaching than Evers’, would have increased statewide levy authority by more than $90 million. Property tax increases under Evers’ proposal can’t be estimated at this time. When the Legislative Fiscal Bureau (LFB) concludes its work analyzing the budget with its nonpartisan pen, we hope to add those figures to this piece.

Students in poverty would get additional weighting in the funding formula under Evers’ proposal, which seeks to add a 0.2x multiplier for poverty. If a student qualifies for free or reduced lunch, they would count as 1.2 full-time equivalent students (FTE). That will increase the apparent pupil amount at districts like MPS, which will then see higher levels of every form of aid to reflect their higher pupil count under the more generous formula.

The budget would also spend more than $600 million on students with special needs. The majority of the hike would go toward increasing the state’s reimbursement level for special education costs by $606 million over the biennium. The high-cost special education program would be made sum sufficient – meaning that the program will be fully funded at whatever level it needs, essentially a blank check. Special education transition readiness grants would increase from $1,000 per pupil to $1,500 per pupil, increasing spending by more than $7 million on those grants.

The plan does away with current restrictions on the number of referenda that a school district may hold in a year, changes that were a part of Walker’s and the Legislature’s push to keep property taxes frozen.

Other changes to public school finance include a number of funding increases, or entirely new programs, for target areas. Many of the proposals are ideas that came from the Blue Ribbon Commission on School Funding, which met this year and last year to discuss ways to change Wisconsin’s school finance formula.

In the second year of the biennium, a new level of sparsity aid would be created to help school districts who stop qualifying because of an increase in enrollment. Sparsity aid is meant to go to rural districts with sparse, spread out student populations. That change would cost $9.8 million.

Student mental health needs would be funded by more than $63 million for in-school pupil services, staff training, and other related initiatives. A new Urban Excellence Initiative would spend more than $15 million on closing achievement gaps in the state’s five largest public school districts. Funding for a host of bicultural-bilingual programs would be increased, including a $35.3 million increase to bilingual-bicultural program reimbursement. A new $2.4 million program that would provide $100 per English learner would also be created.

After-school and out-of-school grants would be created to the tune of $10 million annually. Tribal language revitalization grants, robotics league participation grants, the Special Olympics of Wisconsin, and Very Special Arts of Wisconsin, among others, would see grant funding increased.

Changes with no fiscal note attached include a provision that requires teachers to have 45 minutes or a single class period in planning time every day, whichever is greater.

The plan does away with current restrictions on the number of referenda that a school district may hold in a year. Those changes were ushered in over the past few legislative sessions as part of Walker’s and the Legislature’s push to keep property taxes frozen. Currently, school districts can only pose referenda questions during regularly scheduled general and primary elections. Voters have approved $9.7 billion in tax increases via referenda since 1999, according to a Wheeler Report analysis released last summer.

The Joint Finance Committee will begin its work parsing through the document next month. As always, MacIver will be here with in-depth analysis and coverage.