Wisconsin Union Membership 2017 Update

MacIver News Service | October 20, 2017

By Jake Lubenow

MADISON, Wis. – There have been many lessons learned in Wisconsin’s collective-bargaining reform era. Perhaps the most important takeaway is what has ever been true: When people are allowed the power to choose, they exercise that power.

The laws that have lifted the yoke of compulsory union membership off the backs of Wisconsin workers have empowered employees in the public and private sectors to walk away from big labor.

And they have done so in droves – even in the metropolitan area of the People’s Republic of Madison, where the union membership rate has sunk to 5.4 percent.

Union membership has plummeted in the Badger State in the wake of the Act 10 and the right-to-work reforms led by Gov. Scott Walker and the Republican-controlled Legislature.

The most recent data show union membership statewide has declined from 354,882 members in 2010 to 218,233 in 2016, a decline of 38.5 percent.

Act 10, passed and signed in 2011, broadly limited the power of public sector unions, returning control to the taxpayer. It also gave public sector unions the right to decide whether they wanted to continue to pay the union dues that they had so long been forced to contribute, or whether they wanted to remain in the union at all.

The legislation has saved the state over $5 billion since its implementation. More than $3 billion was saved thanks to modest contributions to benefits from public employees, and the reform saved the struggling Milwaukee Public Schools over $1 billion.

The right-to-work law followed four years later, giving private sector unionized workers the ability to opt-out of union membership. Wisconsin was the 25th state to implement the worker liberty reform, joining a wave of six other states in the past 10 years that have passed similar freedoms.

Wisconsin Union Membership, the Latest Data

Since Act 10 and right to work, there have been some interesting developments across Wisconsin. UnionStats.com compiles Census Bureau data and provides a great look at some of the Wisconsin metro areas’ union data.

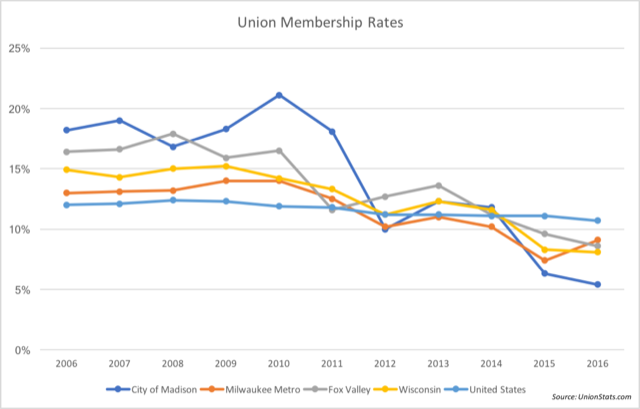

Statewide, union membership rates have fallen from 14.2 percent in 2010 to 10.7 percent last year, the most recent data available.

In the metro area of Madison, a hive of organized labor, union membership has decreased significantly since its peak of 21.1 percent of the workforce in 2010. When the law really started to effect change in contracts in 2012, the rate dropped to 10 percent. The state’s capital city employs many of the state employees affected by the legislation, – many of whom joined the massive, big labor-led protests against Act 10 at the Capitol in late winter 2011.

Despite liberal Madison’s seeming love of unions, only 5.4 percent of Madison area workers were union members in 2016. While there were well over 56,000 members in the Madison metropolitan area in 2010, there were just over 20,000 as of the most recent data.

The Fox Cities area, including Appleton, Oshkosh, and Neenah, also has seen declines, although not as pronounced as Madison. A peak of 16.5 percent in 2010 followed a drop in 2011 to 11.6 percent. Similar results followed the introduction of right-to-work freedoms, with a drop from 11.2 percent to 9.6 percent from 2014 to 2015. Union membership continues to decrease.

The Milwaukee metropolitan area saw a sharp decline in union participation following implementation of the right-to-work law. In 2014, the rate was 10.2 percent before dropping to 7.4 percent in 2015. The rate has since risen to 9.1 percent.

Overall, the state of Wisconsin has seen recent decreases across the board, including declines following both reform measures. The worker exodus from union was more dramatic early on. A 29.1 percent drop in union membership rates in 2015 was succeeded by a modest decline from 8.3 to 8.1 percent in 2016. Close to 355,000 employees were union members in 2010. More than 125,000 Wisconsinites have left their unions since 2010, with only 218,000 members today.

Big labor painted the departures as the result of “(r)elentless attacks from right-wing politicians and corporate special interests.”

“Today, it’s much harder for working people to join together in a union and fight for fair wages and safer workplaces,” Rick Badger, executive director of state employee union AFSCME Council 32 told the Wisconsin State Journal earlier this year.

In fact, it’s easier for workers once forced into paying union dues to free themselves from the clutches of powerful labor organizations with a liberal political agenda.

Neither reform measure in Wisconsin forced workers out of their unions, but rather provided employees with the opportunity to chose whether their union dues were providing enough benefit to justify participation. It’s like any other product or service in consumerism. Customers go – and stay – where they find value.

Public and Private Union Membership

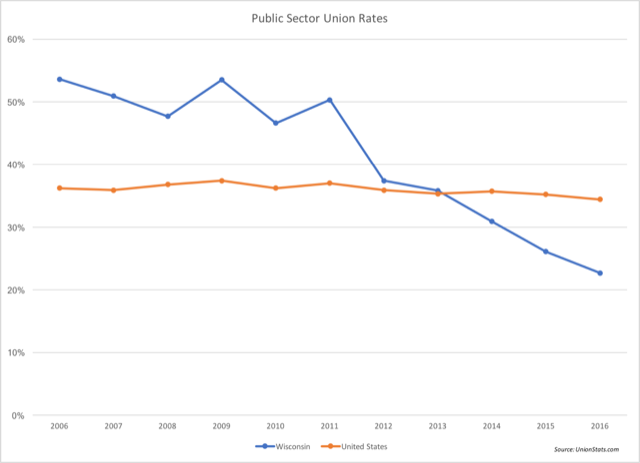

With the two reforms coming four years apart, Wisconsin has had a unique opportunity to see the differences public and private sector union changes have on each sector separately.

The public sector has seen a steep decline from 2011 through last year, with only a short year of relief for unions in 2013 when the rate decrease wasn’t as drastic. The rate has continued to fall as more public-sector employees see less value in union membership.

The Wisconsin Education Association Council (WEAC), the state’s largest teachers union, has seen its membership rolls plummet. WEAC boasted approximately 100,000 members before Act 10. In 2016, the union counted 36,000 members, as reported by the MacIver Institute. WEAC was a long-time supporter of Wisconsin progressives, holding taxpayers hostage with expensive public-sector employee contracts. It used, and continues to use, its members’ money to support Democrats and union-friendly candidates. WEAC was once Wisconsin’s mightiest lobbying force, spending $1 million lobbying the state Legislature in the first half of 2009 alone. WEAC’s political action committee has spent next to nothing since the recall elections in 2012.

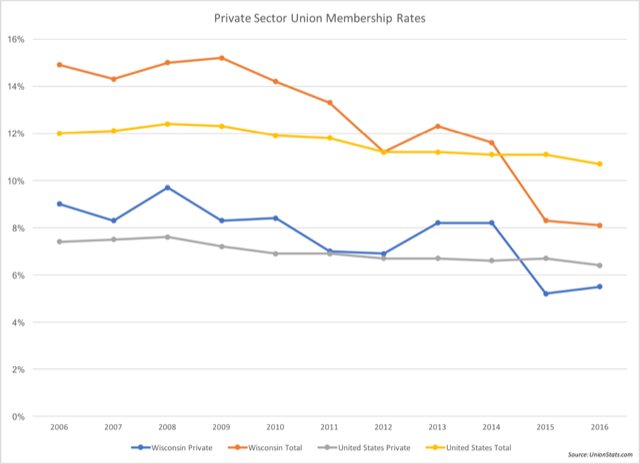

Private sector unions have fared a bit better. Right to work does not place limits on collective bargaining like Act 10 does, nor can it under labor laws. Rather, the law simply prohibits compelling workers to participate.

Private-sector membership dropped significantly after right to work passed but stabilized (even increased slightly) in the year since.

Public-sector unions will have to continue to fight hard to prove their worth to newly empowered members if they do not want to experience the same retention problem the public-sector has.

In 2015, Wisconsin’s three AFSCME councils merged. Badger told the State Journal that the union “is getting back to organizing basics” and rebuilding grassroots efforts. What that means in terms of customer value isn’t clear.

Wage Premiums

One of unionists’ favorite talking points is the wage premium, or the amount a union worker makes over a non-union counterpart. Given the top-ranking states in wage premium are right-to-work states, there is further evidence that liberating workers from compulsory union membership is a benefit for labor.

A 2016 report by the Midwest Policy Institute calculated the states with the highest wage premium. Wisconsin had the 12th highest (10.99 percent). Of the eleven states that ranked higher, eight are right-to-work states as well, including all of the top five.

Union leaders have conveniently ignored the reason right-to-work states rank higher. When union members have the choice to participate or not, employees receiving a lower wage benefit often leave their unions, and those benefitting remain.

Free-market principles dictate that an effective union that provides substantial benefit, or at least perceived value, need not worry about members leaving in a right-to-work state.

The accuracy and relevance of the wage premium statistic, however, have been hotly contested in recent years and it’s difficult to measure whether union members see a benefit in wages at all.

Public Sector Employment

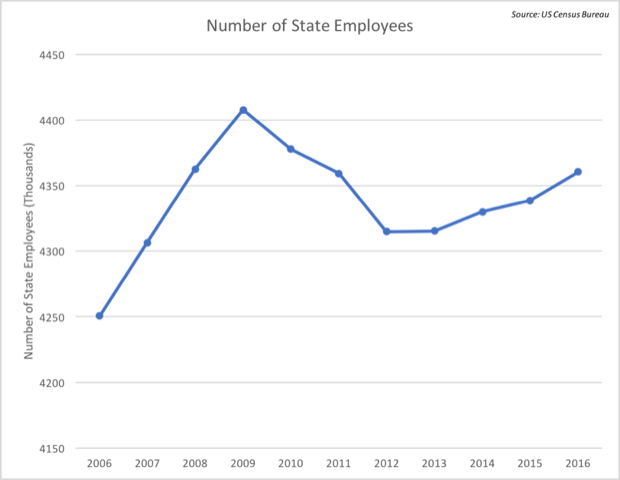

In the fight over Act 10, union officials declared that state employees would leave the public sector in record numbers. It turns out that’s not true. While there was a substantial decrease in public-sector employees following the economic downturn of 2009, there has been an uptick in state workers since 2012.

The public sector still pays well and the minimal contributions that state employees have to pay into their benefits have not caused a government worker exodus. In fact, the 12 percent minimum health insurance contribution stipulated in Act 10 to help reduce costs, is still far below the Midwest private sector average contribution of 22 percent.

While the number of state employees has not decreased significantly, the number of public-sector union members certainly has. When given a choice, workers are choosing workplace freedom over compulsory union dues.

M.D. Kittle contributed